Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe. The Back-Up Brigades

The Back-Up Brigades

Did you have an ancestor who was a part-time soldier in the late 18th Century? New militia muster records online could help you advance your research

The tradition of militias in England, providing a reserve force of non-professional soldiers in times of crises, dates back to Anglo-Saxon times. By the 16th century, the militia had become an important institution in English life. Now the largest collection of militia records available online have been released at www.thegenealogist.co.uk, and could help you explore your 18th century ancestors.

The early militia was organised on the basis of the shire county, and was one of the responsibilities of the Lord Lieutenant, a royal official (usually a trusted nobleman). Each of the county hundreds was likewise the responsibility of a Deputy Lieutenant, who relayed orders to the justices of the peace or magistrates. Every parish furnished a quota of eligible men, whose names were recorded on muster rolls. Likewise, each household was assessed for the purpose of finding weapons, armour, horses, or their financial equivalent, according to their status. The militia was supposed to be mustered for training purposed from time to time, but this was rarely done. The militia regiments were consequently ill-prepared for an emergency, and could not be relied upon to serve outside their own countries.

After the English Civil War, Parliament distrusted the creation of a large standing army not under civilian control. Both Whigs and Tories preferred a small standing army under civilian control for defensive deterrence and to prosecute foreign wars, a large navy as the first line of national defence, and a militia composed of their neighbours as additional defence and to preserve domestic order. The English Bill of Rights of 1689 declared "that the raising or keeping a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, unless it be with consent of Parliament, is against law...".

The Militia Act of 1757 created a more professional national military reserve. Better records were kept, and the men were selected by ballot to serve for longer periods. Proper uniforms and better weapons were provided, and the force was 'embodied' from time to time for training sessions.

In a time of increasing political uncertainty abroad it was felt necessary to have the security of a 'backup', part-time force in case of invasion. Britain was often in military conflict with the French and Dutch and it was felt that a homeland security force was essential to guard home soil.

The militia were posted at several strategic locations, in particular the South Coast of England, Wales and Ireland. A number of camps were held at Brighton, where the militia regiments were reviewed by royalty – this is the origin of the song 'Brighton Camp'. The militia could not be forced to serve overseas, but it was seen as a vital training reserve for the army. Bounties were offered to men who opted to subsequently 'exchange' from the militia to the regular army.

In the colonies, the British set up the use of militias to protect their interests, as regular troops were often too far away to be used. This was particularly seen in North America in the French and Indian Wars before 1774. The loyal militia were often the primary 'English' force in the field.

Militias based in England were little used but still felt necessary. The only action on home soil was the Battle of Jersey in 1781, when the Royal Militia of the island of Jersey combined with regular British Army troops to repel a joint French and Dutch invasion force. The British commander, Major Francis Peirson, was killed as the battle reached its climax, but victory was gained and the invading forces defeated. The battle of Jersey reinforced the perceived need for militia help.

The Militia Act of 1757 offered all 'able-bodied' men to serve in the militia at home in order to counter any threat arising while the majority of the regular army was stationed abroad. Lists of eligible men in each parish were known as 'militia ballot lists' and from these, the men actually chosen appeared in the militia lists, of which more than 58,000 now appear online at TheGenealogist.

The militias were funded by Land Tax and received a 'marching tax' and expenses for attending

meetings. As the militias were part-time they were called up at times of war, such as the latter stages of the American War of Independence when France and Spain both declared war on Britain and there was a national threat to the country. In between wars, the militias were disbanded and not required to meet.

The records on TheGenealogist are a list of four significant 'musters' or organised meetings in which all the regiments of the militias are brought together and names are recorded. These records provide us with a snapshot of who was serving, with what regiment, and in some case the dates they were serving, when they were discharged, or if they died in service.

These records cover musters in 1781 and 1782 and form the largest number of surviving records available for this era. They join the largest collection of Army Lists available online, establishing TheGenealogist as a major military research site.

The records cover people from all walks of life who made up the officers and men. From MPs to landowners, from carpenters to labourers, if they were physically up to it, they could be selected for the militia.

Regiments covering all of England and Wales are represented in these new records. The original records are from The National Archives series WO 13 and feature the muster and pay lists of all members of the militias. Men received 'marching money' when the militia was mobilised and were paid expenses for local meetings. County regiments, although recruited locally, often served away from home and these indexes tell precisely where, under whom and on what dates the men were mustered.

These newly online militia lists can further help track the movements and lives of our ancestors before census and civil registration times.

Case Study: A Colonel and a Private

At TheGenealogist.co.uk, it's easy to search for an ancestor to see if they served in any of the militia regiments in the 1780's. Search by name and any relevant keyword, or use the advanced search to narrow it down to 'Corps', 'Company' or the 'Rank' of the soldier.

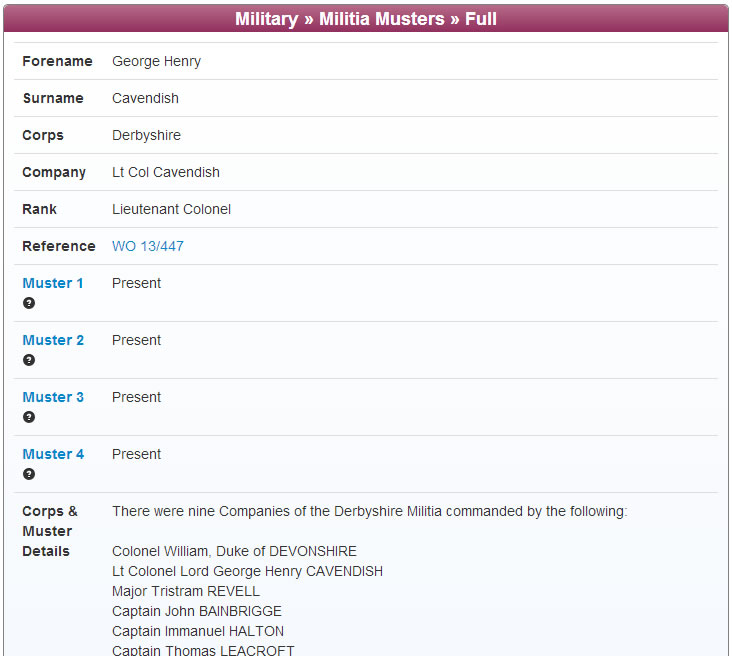

Below you can see a well-known 'militia man' of the time, George Henry Cavendish, a Whig politician who was nominated as a colonel in the Derbyshire Militia in 1783. He was the younger son of William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, and spent a lifetime in politics, representing the town of Derby as a Member of Parliament. He was well renowned for his for his Whig principles and had a long career in the House of Commons and later House of Lords. His wealth and status guaranteed him a decent 'rank' in the Derbyshire Militia.

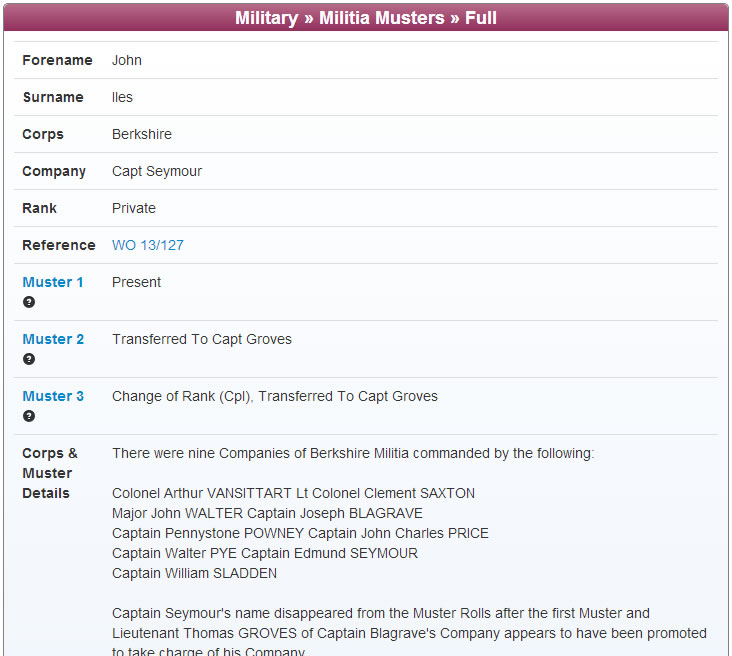

Below we see the details of Private John lles of the Berkshire Corps. In the first muster, he is serving in Captain Seymour's company, in the second muster he has transferred to Captain Grove's Company and by the third muster he has received a promotion to the rank of Corporal in the Berkshire militia.

The records show the location of the musters and how long the regiments were gathered there. The muster documents had to be formally signed by a respected official, such as Justice of the Peace.