Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.A Life Spelt Out

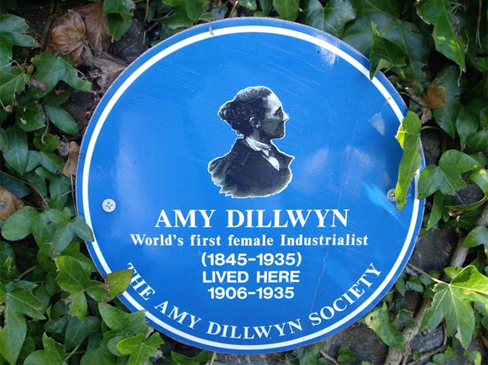

Nick Thorne investigates the story of an Extraordinary Welsh Woman, Spelter-making Industrialist, Novelist and Suffragist Amy Dillwyn

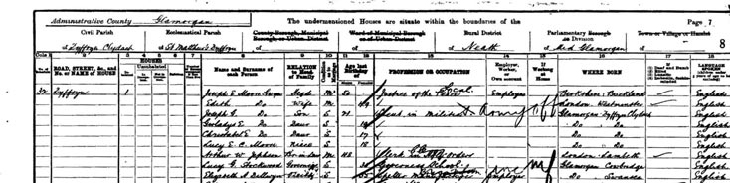

In the 1901 census of Neath, there is an entry for a single lady of 55. She is a visitor spending census night at a house of a justice of the peace in Dyffryn Clydach, near to the ruins of Neath Abbey. Elizabeth A. Dillwyn’s occupation has been given to the enumerator as spelter manufacturer, which attracted my attention for being an unusual job for a lady at the time.

Wondering what spelting was, I found the explanation on Wikipedia that spelter is a zinc–lead alloy that ages to resemble bronze, but is softer and has a lower melting point. The name can also refer to a copper–zinc alloy (a brass) used for brazing, or to pure zinc. It is often used to produce sculptures, figurines and candlesticks.

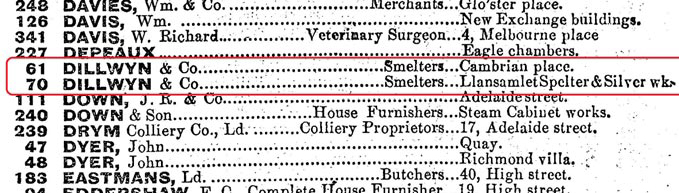

By stating that Miss Dillwyn was a spelter manufacturer, the census seemed to be indicating that she was the principal of a business and in charge of the enterprise. Realising that at this time it would be uncommon to find a woman running a manufacturing business, I was intrigued. I quickly discovered her company listed in the Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories collection on TheGenealogist. An online book that I found then told me that Dillwyn & Co had become one of the largest zinc manufacturers in the country – but that it was not always that successful. Indeed, when she had taken it over, after both her father and brother had died within a short time from each other, she had been confronted with huge debts and the enormously difficult prospect of saving the company and its workforce. That she achieved this in a world dominated by male factory owners is impressive.

The eccentric lady with the cigar

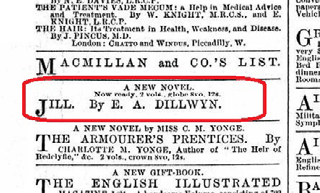

Amy Dillwyn was considered eccentric. She wore ‘mannish’ clothing and smoked cigars, somewhat echoing the story of Yorkshirewoman Anne Lister, from half a century before, whose story has recently been the inspiration for the Gentleman Jack television programme. While Anne Lister kept a journal, Amy found time to be a published author as we can see from an advertisement in the Illustrated London News for September 1884 and discovered by searching TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazines collection. The book, promoted by the major publishing house of Macmillan and Co., was titled Jill and was a novel that would appear outwardly to its readers to be a feminist statement – but it is also recognised as a poignant unrequited love echoing its author’s sexuality.

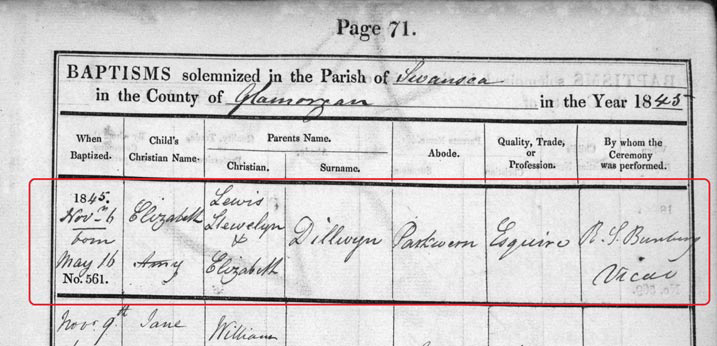

Although her full name was Elizabeth Amy Dillwyn, she was known as Amy. Born in Sketty, Swansea, she was the daughter of Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn and Elizabeth (née De la Beche). Searching TheGenealogist’s Welsh parish records, we are able to find her baptism in the parish of Swansea on 6 November 1845. The records register that her birth had been on 16 May 1845 but they don’t explicitly tell us her father’s occupation, noting only the word ‘Esquire’ under his ‘Quality, Trade or Profession’.

The Illustrated London News, 20 September 1884, from TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazines collection

Baptism of Amy Dillwyn in the Welsh parish records, 1845, at Swansea

Early telephone directory from TheGenealogist’s Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories collection

The records that reveal more

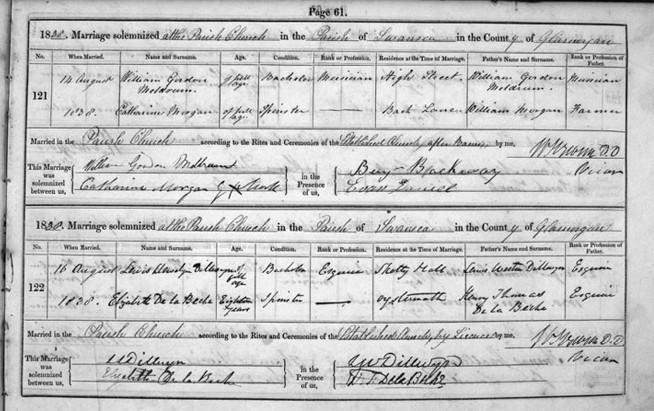

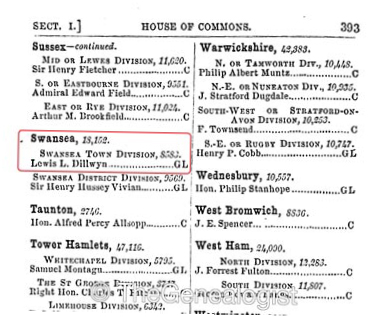

From the baptism record for Amy we know that her parents were Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn and his wife Elizabeth. To reach back a generation, searching the Welsh Anglican parish registers on TheGenealogist allows us to find their marriage in 1838. Amy’s father is recorded to be of full age, that is over 21, but his bride is just 18 and is the daughter of Henry Thomas De La Beche. The groom gave his residence as Sketty Hall and his father as Lewis Weston Dillwyn. Researching within the records on TheGenealogist finds an entry for Amy’s father in the Edinburgh Almanac. This publication includes a listing for all the members of the House of Commons, not just those from Scotland, and identifies Lewis L. Dillyn as the Member of Parliament for Swansea in Wales.

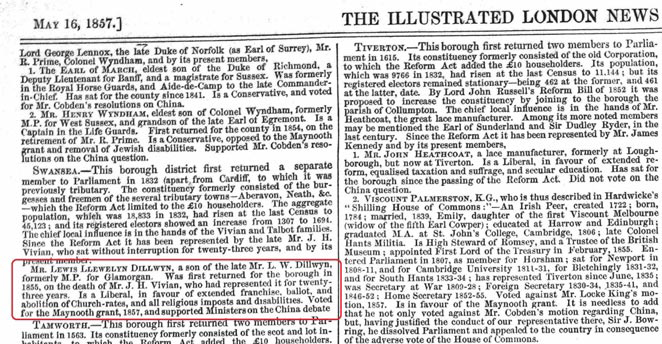

Another search result, this time from the Newspapers and Magazines on TheGenealogist, furnishes us a little more information including that he was first returned to Westminster in 1855, that he was the son of L.W. Dillwyn, a former MP for Glamorgan, that he was a member of the Liberal party, and details some of the policies that he was in favour of.

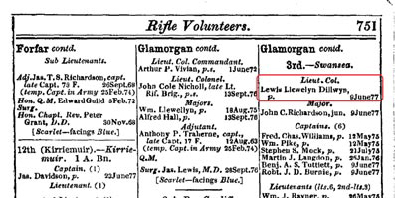

The military records show us that Amy’s father held the rank of a lieutenant colonel in the 3rd (Swansea Rifles) Glamorganshire Rifle Volunteers in 1877 from consulting one of the Army Lists on TheGenealogist.

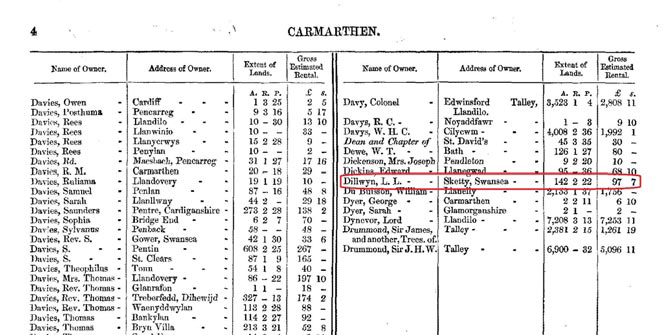

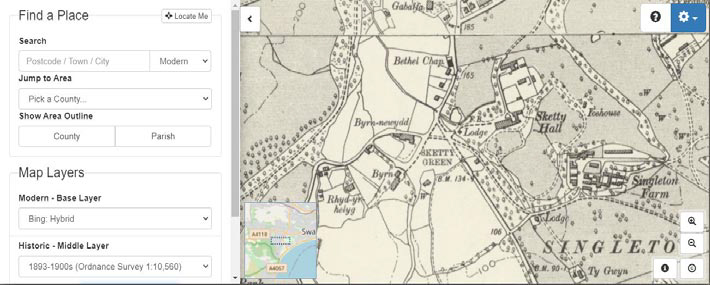

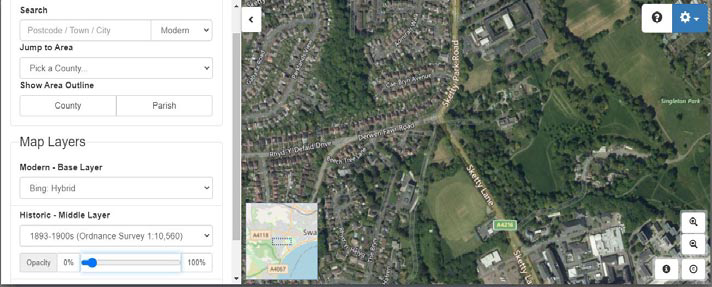

Previously we had noted that on his and Elizabeth’s marriage entry in the church register Lewis gave his residence as Sketty Hall. Consulting the land and property records on TheGenealogist allows us to find that Lewis was the owner of over 142 acres in neighbouring Carmarthen and by using the Map Explorer tool on TheGenealogist we are able to locate the exact location of Sketty Hall and its grounds. The ability to fade between the old and the modern georeferenced maps in this interface shows us that Sketty Hall is still in existence today, though the satellite map lays bare just how much the area outside its grounds has become built up with suburban housing. The family moved to Hendrefoilan House, a large private house that Lewis had built in 1853; we can use the Map Explorer to see is not very far away from Sketty Hall.

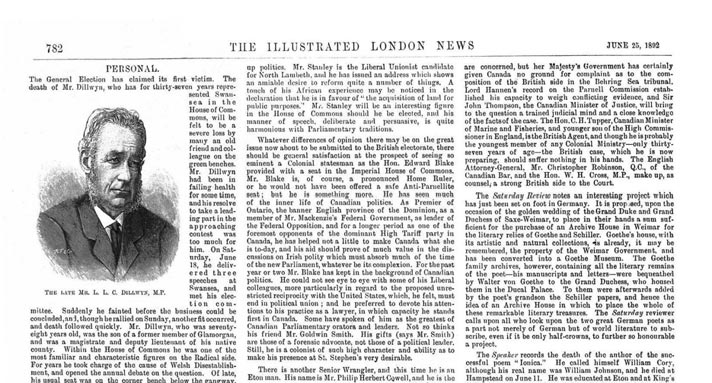

When Amy’s father died in June 1892 after representing Swansea as its MP for 37 years, the Illustrated London News ran a piece on his passing. He had been campaigning in the run-up to a general election and had just delivered three speeches in Swansea and had then met with his election committee when he fainted and the business could not be concluded. The next day he at first rallied, but then took a turn for the worse and died. Amy had lost her brother two years earlier and the death of her father was a blow for the family as well as their spelter business.

The paper had noted in their article that Lewis Dillwyn was on the Radical side and for years had been in charge of the argument for the disestablishment of the Anglican Church, opening the annual debate on the question in Parliament. From this stand it might have been expected that he would have belonged to a Nonconformist church, as so many Welsh people did. Although his ancestors were Quakers, it was at the Church of England parish church in Wales that his baptism, marriage, and indeed his burial, took place. We can find each of these records from a search of the Welsh Anglican parish records now on TheGenealogist.

Marriage record for Lewis L. Dillwyn and Elizabeth De La Beche 1838

Army Lists from the Military Records collection on TheGenealogist

The Illustrated London News reveals some information about Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn MP

Amy’s Quaker grandfather

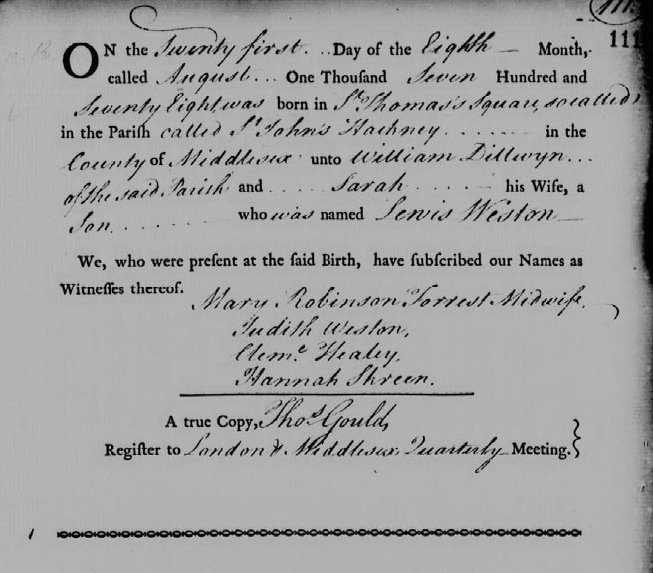

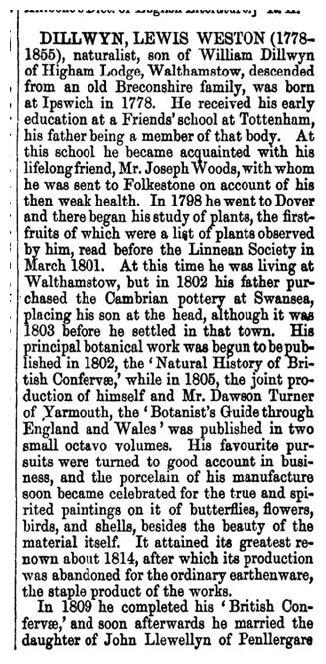

From the newspaper articles, and by seeking out his baptism in St Mary’s, Swansea we already know that Lewis’s father had been Lewis Weston Dillwyn. Turning to the Master Search on TheGenealogist to search for records of the grandfather of Amy, we come across him in the Occupational records and his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. This tells us a lot more about the family, revealing that his father had been William Dillwyn of Walthamstow and that the Dillwyns could trace their antecedents back to Breconshire. William had been a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers) and sent his son to a Quaker school in Tottenham. As a Quaker, who would not practise baptism, William had his son’s birth registered at a Quaker meeting in Middlesex in 1778, as we can find from the RG6 Nonconformist records on TheGenealogist. But Lewis chose the Anglican church to have his own son baptised in Swansea.

Amy’s grandfather would become a renowned naturalist and published works on botany and conchology, including his 1809 work The Natural History of British Confervae, an illustrated study of British freshwater algae. In 1803 he moved to Swansea to manage the Cambrian Pottery, which his father, William, had purchased in 1802. Lewis Weston Dillwyn also became one of the two Members of Parliament for Glamorgan, standing for the Whig Party.

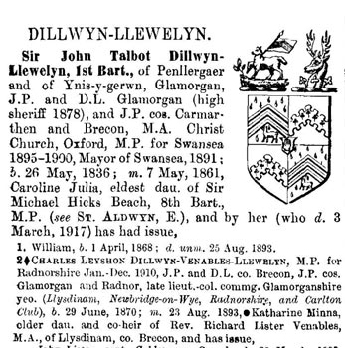

Another useful record that helps to add generations to the Dillwyn family tree is the entry for Amy’s cousin Sir John Talbot Dillwyn-Llewelyn in Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage, which can again be searched on TheGenealogist. This lists a further three generations of their paternal line and shows that William Dillwyn of Walthamstow was the son of John Dillwyn of Philadelphia in America, himself being the son of an earlier William who had emigrated from Breconshire with his friend Governor Penn. We are also able to read that Amy’s mother, Elizabeth, having married Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn is noted as being the heiress of Sir Henry Thomas De la Beche.

A search of the tithe records on TheGenealogist shows us that Lewis Weston Dillwyn was a notable landowner and so it would seem from these records that the family had been a wealthy one. But at the death of Amy’s father, she inherited not wealth, but her father’s debts of over £100,000 (£8 million or more today). She was forced to move out of the family home and into lodgings while trying to steer Dillwyn’s spelter works back to profitability. The house that her father had built at Hendrefoilan was not hers to sell due to a limit on the inheritance of the property that required it to pass only down the male line.

It took ten years, until 1902, before she was able to leave the lodgings and lease a small house of her own. Then, when the business was finally solvent enough for her to buy her own house in 1904, she moved to Tŷ Glyn and this is the residence that we can find her living at in 1911 from a search of that year’s census. It is also her last home as can be seen by its inclusion in the burial register for St Paul’s Church at Sketty. The entry is also interesting as it notes not only that she lived to the age of 90, but that it was burial ‘after cremation’. In her novel, Jill, published back in 1884, Amy had included a passionate argument for cremation in the book – the practice only being sanctioned in Britain in 1885.

At Dillwyn’s Amy had employed a manager to run the works on a day-to-day basis, but she was very involved in the business and was said to work daily at her offices dealing with correspondence for the company in both French and German as well as overseeing the finances. She brought her nephew into the business and began teaching him the ropes. Eventually, however, she received an offer for the company in 1905 from a large German enterprise which she realised was in the best interests of Dillwyn & Co. Though she missed being involved she sold most of her shares while securing her nephew on the board.

Amy Dillyon was always known to be a strong supporter of social justice and so it is not a surprise that she gave her support to striking seamstresses in 1911. When the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies was formed at the turn of the century, Amy joined as one of its earliest supporters in Wales. Although she rejected the militant actions of some of its members, she was nonetheless a committed member of the movement.

From an intriguing entry in a census identifying a woman as a manufacturer, to clues found in parish records, directories, newspapers and landowner records, the story of this unusual Welsh woman and her family is an absorbing one.

Carmarthen Landowner Records on TheGenealogist

Sketty Hall on the Map Explorer historical map

Sketty Hall on the modern Bing layer

Lewis L. Dillwyn MP in the 1891 Edinburgh Almanac on TheGenealogist

Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage can be searched on TheGenealogist

RG6 Nonconformist records can be searched on TheGenealogist

Obituary in the Illustrated London News, 25 June 1892

TheGenealogist’s Occupational records reveal Lewis Weston Dillwyn’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography