Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe. A May to remember

A May to remember

Keith Gregson marks the centenary of Britian's worst railway disaster, which has often been overlooked because it occurred in the midst of World War One.

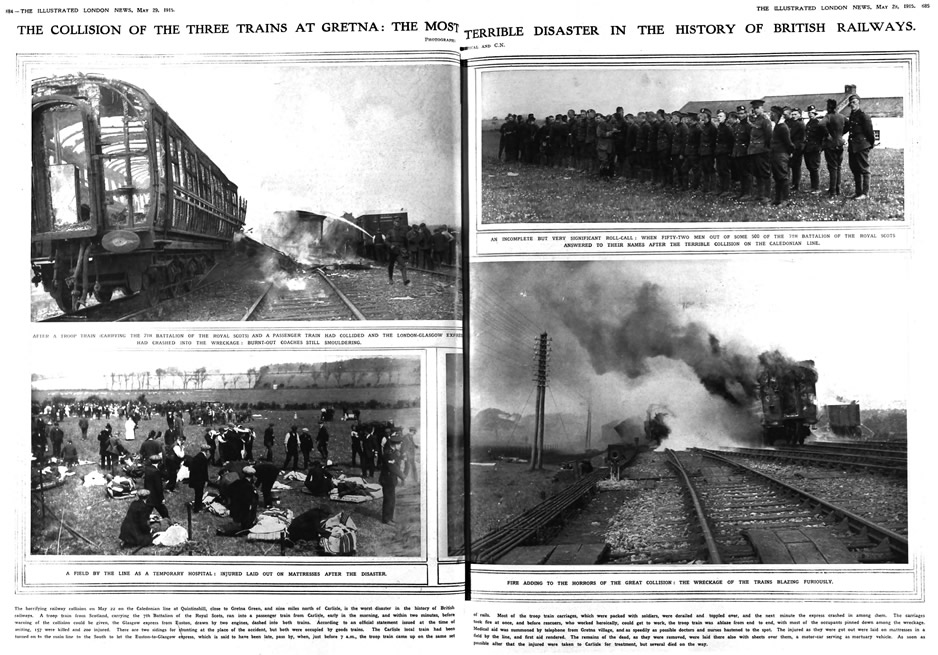

The Queen famously described the year 1992 as an annus horribilis. The monthly equivalent of 1992 may well have been May 1915. During that month, the Lusitania was sunk off the coast of Ireland with the loss of over 1,000 lives. At the same time the bloody Second Battle of Ypres was reaching its climax and the Gallipoli campaign was beginning to grind out thousands of casualties. Against this background, Britain's most costly rail disaster took place. On 22 May 1915, a collision involving three trains on the main west coast line just north of the Scottish border resulted in over 200 deaths and an equal number of injuries. The vast majority of casualties were members of the Royal Scots Territorials en route for Gallipoli and, due to the accident's timing in the midst of war, their sad fate has often been hidden in the footnotes of history.

The causes of the Quintinshill or Gretna Green Disaster are still hotly debated, although the basic facts are relatively straightforward. A local or 'parly' train heading north from Carlisle on the up (Glasgow) line had been moved to the down (London) line outside the signal box at Quintinshill to make way for expresses heading north. This was normal practice. However, the 'parly' was still there when it was struckby the troop train heading south from Larbert to Liverpool. Wreckage spilled over onto the up line and minutes later this was struck by the overnight London-to-Glasgow express. Sparks and flames from the damaged engines set light to the ancient wooden and gas lit carriages of the troop train with disastrous results. The accident took place just after 6.30 in the morning and the victims included soldiers, civilians and railway workers. Over the next few hours, doctors, nurses and local volunteers arrived on the scene and many of these later provided eyewitness accounts.

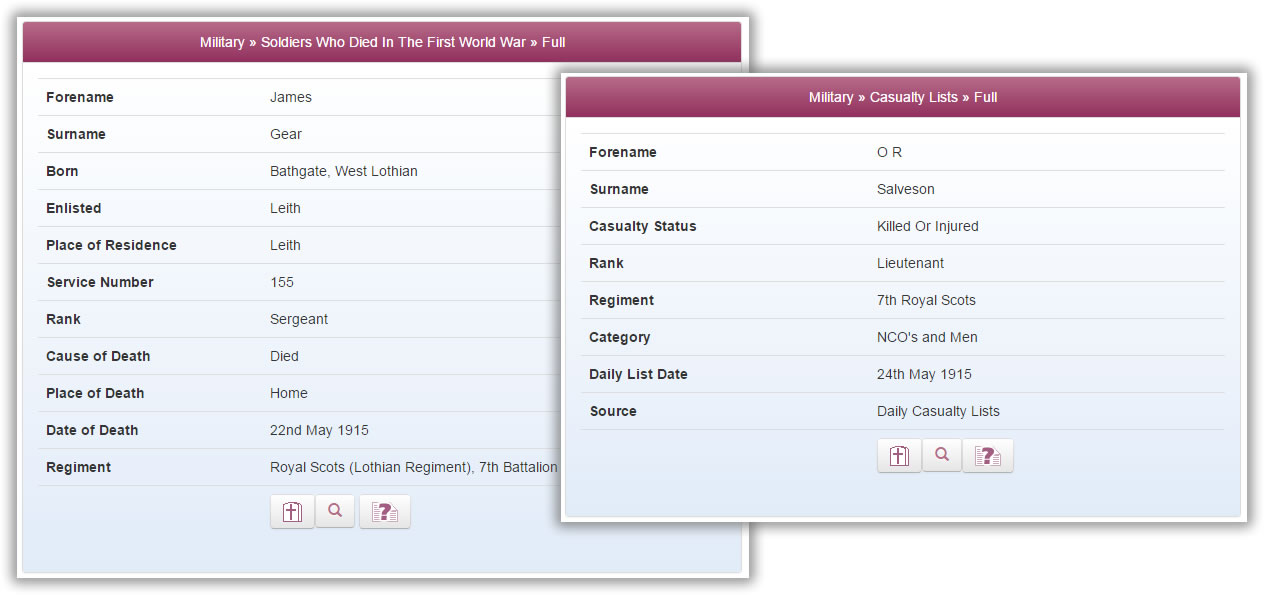

The records of most of the soldiers who died or who were wounded in the accident can be viewed online. They came to be regarded as victims of war (in fact many of the contemporary newspaper accounts described the accident as if it were a battle) thus their details turn up on the various casualty lists which can be viewed at TheGenealogist.co.uk. Nearly all the military casualties were members of 1/7 Battalion of the Leith-based Royal Scots Territorials. For example, the details of Sergeant James Gear who died in the accident can be accessed via the data set Soldiers Who Died In The Great War and a volume relating to the Royal Scots 1914 to 1919. The index to the former reveals that his service number was 155, that he came from Bathgate and that his place of death was "home" on 22 May 1915. Similarly George Schumacher from Leith (service number 1566) and Thomas Ormiston also from Leith (service number 1596) appear in the list of Soldiers Who Died in the Great War.

Details of James Gear from Soldiers Who Died in the First World War at www.TheGenealogist.co.uk. Above right; appearing on the list of the wounded was N G Salvesen (Salvesonon the index) – member of a well-known Norwegian/Scottish shipping family

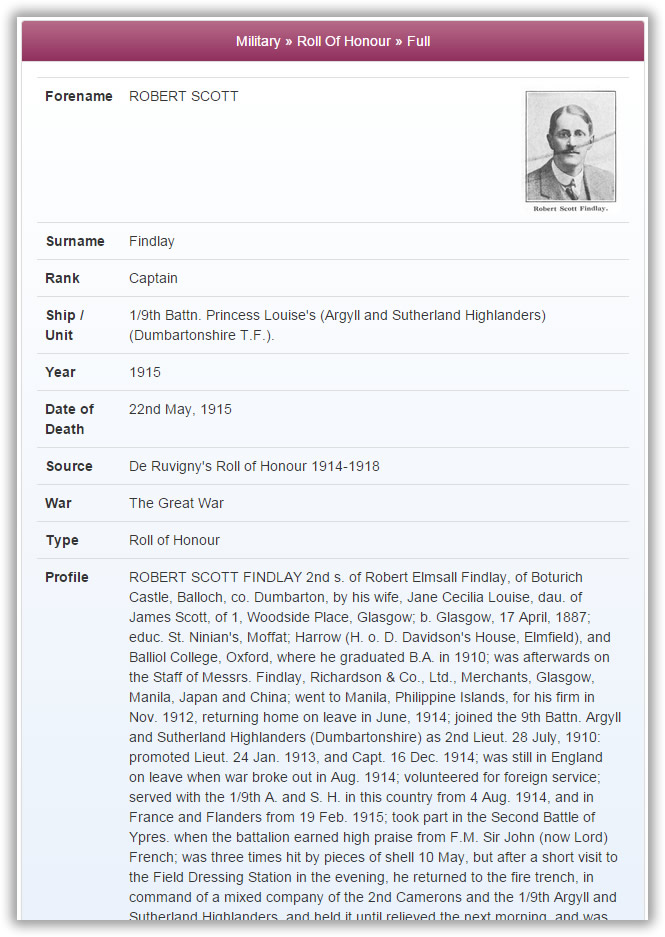

One of the most tragic victims of the accident was Captain Robert Scott Findlay who was travelling home to Scotland on the northbound express. He was in Agryll and Sutherland Highlanders (according to TheGenealogist.co.uk's Roll of Honour Index the 1/9 Battalion a territorial force based on Dumbarton). His family had his photograph and details published in De Ruvigny's Roll of Honour where he is painted as a most talented and brave young man. Lieutenant John Jackson of the same battalion who was travelling with Findlay also appears in the Casualty List, his death dated 24 May 1915.

An account of the disaster from the Illustrated London News, available at TheGenealogist.co.uk. If your ancestor was involved in any major event of the mid-to-late 19th century or during World War One, you may well find an account in the site's ILN collections.

The railway workers

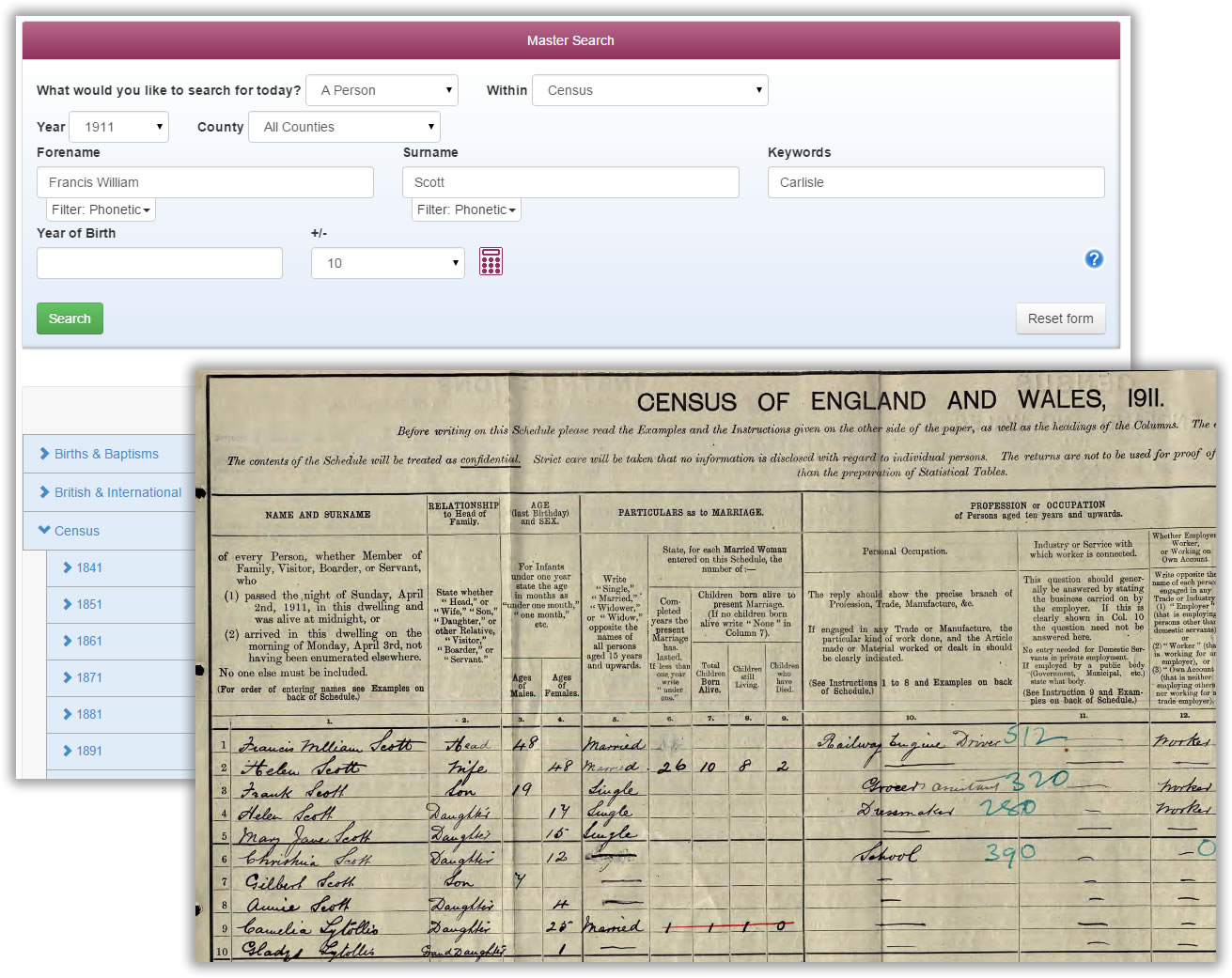

It is also possible to trace some of the railway workers involved in the tragedy. Both the driver and the fireman of the troop train were local to Carlisle and were killed at Quintinshill. The driver, Francis Scott, who was in his early 50's, was well known in the area as he had driven the royal train during his career. His fireman, James Hannah, 20 years younger than Scott, lived just around the corner from him. Both men lived in the Etterby area off Carlisle close to the main sheds and yards for the railway.

As noted earlier, the causes of the accident, both long term and short term, are still disputed. At the time two signalmen who were swapping shifts were blamed for negligence and incompetence and in my youth in Carlisle the received truth was that they had been too busy chatting and had completely forgotten to shift the 'parly' off the down line. They were both imprisoned yet released before the end of their term and re-employed on the railway.

Details of Robert Scott Findlay's service, and his photograph, can be found in De Ruvigny's Roll of Honour, available at www.TheGenealogist.co.uk.

Engine driver Francis William Scott's record in the 1911 census, also at the site

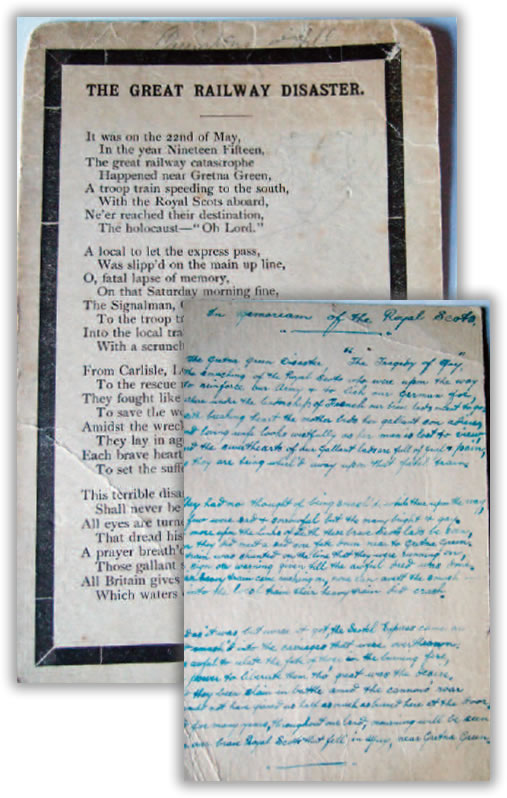

Poems commemorating the Quintinshill disaster, in which more than 220 people died and more than 240 were injured

One of the theories now is that the signalmen effectively in charge at the time was epileptic and that the authorities knew about his condition. He was experienced at his job and the aftermath of a fit might explain why, as he put it, he simply forgot. Long-term, lax practices on the railway were common and were as much the fault of the employers as the employees.

Also the carriages for the troop train, wooden and gas-lit, were virtually redundant and a death trap. They were used because the pressure on the railway in war time was massive and the volume of traffic using the lines high. Perhaps then war itself can be regarded as the main cause of what remains Britain's greatest rail disaster.

Remembering Quintinshill

There is strong tradition in Britain of remembering disasters (particularly mining disasters) by writing related songs and ballads. Often these would be sold to raise funds for those affected by the disaster. Featured here (right) are two postcard ballads picked up at 'elephant shops' in Carlisle during the 1970's. The printed poem is simple and emotional. The handwritten one lends itself well to adaptation to song and the meter of the ballad even suggests that the tune could be an ancient Scottish/Irish one that actually mentions Gretna Green (transcription and a musical setting available from Keith Gregson via www.keithgregson.com).

Personal Connection

I have been aware of the Quintinshill Disaster since my childhood in Carlisle as my maternal grandmother was one of the nurses rushed out to the scene. She spoke often of a Dr Balfour-Paul, who was one of the chief medical helpers after the crash. She also told me that she felt helpless as she had little in the way of medical equipment except a tin of neat Jeyes' Fluid. I (mistakenly) thought she travelled to Quintinshill on a cart but now believe she must have caught the special train. In one of the recent books (see endnote to main text) it is noted that the matron at the Cumberland Infirmary, where my grandmother worked, dispatched two nurses and a porter as soon as news of the tragedy came through. The other book refers only to one nurse by name – Nurse Stephens. That was my grandmother's later married name but she may well have provided an eyewitness account years on from the disaster. Fairly recently my mother, now in her 90's, told me a family tale I had not heard before. She said that her mother had been asked by a young doctor at the scene to help him to carry an injured soldier across the field beside that railway line. As she picked the poor victim up, his leg 'came off' in her hand. I suspect that my mother had to wait until I was in my mid 60's before I was considered old enough to take in such a gory story – food for thought for all family historians!