Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.A true pioneer

To celebrate Women’s History Month, Nick Thorne explores the records of a pioneering professional woman

March is recognised as Women’s History Month, so to mark it we shall trace the family history of someone who blazed a trail for women in the field of medicine. The glass ceiling may still prevent many women from achieving as much as a man can today, but our Victorian ancestors were even less open to allowing members of the female sex into the male preserve of a top profession. Queen Victoria may have been days away from inheriting the throne, but it was a male dominated world into which Elizabeth Garrett was born on 9 June 1836 at Whitechapel. Her destiny was to shake up the establishment of a male-controlled medical profession, as well as becoming very involved in the women's suffrage movement.

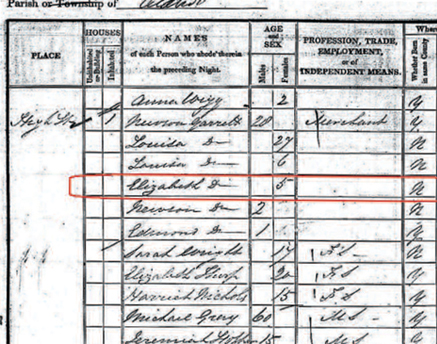

Elizabeth’s birth was registered in the Stepney district of London in the second quarter of 1836, as we can discover from searching the births and baptisms records on TheGenealogist. Her parents were Newson and Louisa Garrett. By the time of the 1841 census, her father had moved the family back from London to Aldeburgh in Suffolk. Newson hailed from the county, as we are able to see by looking at the image of the census on TheGenealogist, from the fact that a ‘Y’ has been entered in the column ‘Whether Born in same County’.

Education, even for girls of her station, would not normally have included science, as young ladies were not being prepared for places at university or to go into the professions. Elizabeth was 18 when she first met Emily Davies, someone who would become a long-standing friend of hers and have a great deal of influence on her thinking. Davies became known as a feminist, suffragist and a pioneering campaigner for women's rights to university access and is credited with being the co-founder of Girton College, Cambridge – the first college to educate women.

Searching TheGenealogist’s Occupational records finds Elizabeth Garrett’s entry in The Dictionary of National Biography 1912-1921. This points us to another important meeting for the young Elizabeth, one that took place in 1859 when she visited London and met Dr Elizabeth Blackwell. Blackwell, although English, was the first female doctor to have qualified in the United States. Encouraged by this example, Elizabeth set her sights on a medical career for herself, knowing that the road to becoming the first woman to qualify in Britain as a physician and surgeon would not be an easy one.

The medical profession was the preserve of the male sex so she began working as a nurse in Middlesex. By this time her sister, Louise, had married a draper named James Smith. A search for them on TheGenealogist finds that, in the 1861 census, Elizabeth and five more of her siblings were staying with the couple and their two toddlers at 22 Manchester Square in Marylebone.

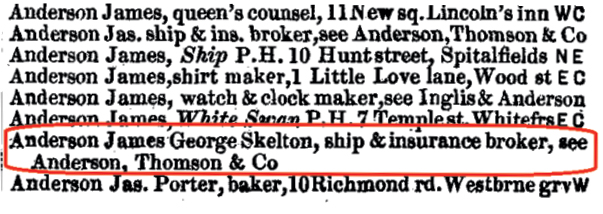

It was also in Marylebone, ten years later in 1871, that Elizabeth got married. The marriage records on TheGenealogist include an index entry for Elizabeth Garrett and James George S Anderson in the first quarter of that year.

Using this information we can now search for her husband in some of the other records on TheGenealogist. In the Trade, Residential & Telephone directories Anderson can be found in the 1869 Kelly’s Post Office Directory and this reveals that James George Skelton Anderson was a ship and insurance broker in Anderson Thomas & Co. Using this business address and, by now looking at the street index, we find the firm at Number 1 Billter Court, 7 Billter Square in the City of London. The company was a co-founder, with F Green & Co, of the Orient Steam Navigation Company that ran ships to Australia – we can also find the two firms listed in the 1897 Who’s Who on TheGenealogist on a page that gives the names and addresses of ‘Our Great Steamship Lines and their Agents’.

Elizabeth Garrett as a child in the 1841 census for Aldeborough, Suffolk

James Anderson in Kelly’s 1869 Post Office Directory

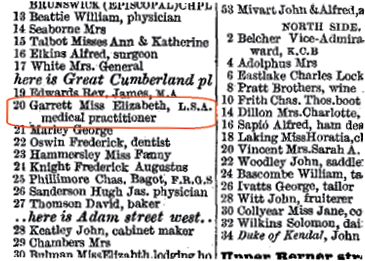

Miss Elizabeth Garrett, LSA in Kelly’s 1869 Post Office Directory

In the same 1869 edition of the Kelly’s Post Office Directory, where we have already found her future husband, Elizabeth herself appears living at 20 Great Cumberland Place. What we can note from her entry is that she has, by that time, become a medical practitioner holding the Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries in London (LSA). The Dictionary of National Biography reveals that she had been denied entry into several medical schools and universities, despite being a talented student. It seems, however, that Elizabeth had found a way to enter medical practice through a loophole in the Society of Apothecaries rules. Rather than study at a medical school, from which her sex was barred entry, she obtained private tuition from some of the teachers who taught at the recognised schools. With their coaching she obtained a certificate in anatomy and physiology and then used it to gain admission to the Society of Apothecaries in 1862. When she passed its exams in 1865, the Society immediately changed its regulations to close off the route that she had used and thus prevent any other women from following in Elizabeth’s footsteps. From then on they would insist that students only train through an accredited medical school.

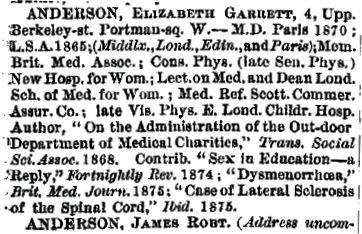

Searching more widely in TheGenealogist’s occupational records, we can also find Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in The Medical Directory for 1895. This entry reveals the years in which she pushed the boundaries of admission to the medical profession in Britain. Apart from the LSA in 1865, we can now see that in 1870, the year before she married James, she had been awarded her medical degree (MD). Unsurprisingly, considering the opposition to female doctors in Britain, the degree was not granted to her in this country, but in Paris.

The Medical Directory for 1895 also provides us with rich clues to help focus our research into this pioneering female doctor. We can read that Elizabeth was a member of the British Medical Association and a consultant physician at the New Hospital for Women. She had become a lecturer at, and also the Dean of, the London School of Medicine for Women and from this record we can see how far she had pressed forward the cause of women doctors.

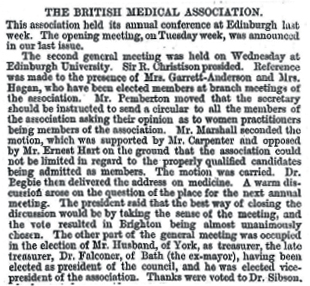

A number of newspaper articles in TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazine collection, however, give us an idea of how hard it had been for her. The Illustrated London News in August 1875, for example, published a report in which Elizabeth was mentioned: the BMA was holding its annual conference in Edinburgh and, at the second general meeting, reference was made to the presence of Mrs Garrett-Anderson and Mrs Hagan, who had been elected members of the BMA at branch meetings. The gentlemen of the BMA were not giving up their closed shop easily. A proposition was introduced at the meeting to send out a circular to all members to find out what their opinion was as to women practitioners being in the BMA.

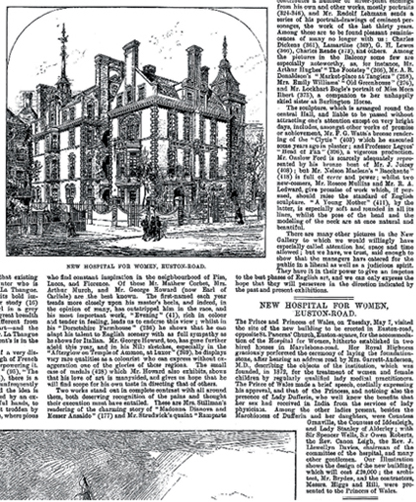

Despite the antipathy displayed here, other articles in The Illustrated London News show us that in her struggle to establish the New Hospital For Women, and to also train other women to be doctors, Elizabeth had some powerful men on her side. In July 1874 no lesser person than the Earl of Shaftesbury chaired a meeting at which she spoke advocating women being treated by members of their own sex. Turning to an 1875 article in The Illustrated London News, the Earl was also reported to be presiding at the distribution of prizes at the London School of Medicine for Women. Mrs Garrett-Anderson and a number of other important people expressed the hope and belief that women should receive a thorough medical education and that legislation would soon be changed. It was, in fact, the very next year that parliament passed the new Medical Act, legislation which finally permitted the medical authorities to grant all qualified applicants a licence to practice medicine, no matter what their gender was.

This was by no means the only high profile support that she had. Another look at the newspapers and magazines on TheGenealogist finds that HRH The Princess of Wales, assisted by the Prince and their daughters, laid the stone for The New Hospital for Women at Euston Road London on 7 May 1889, an institution that Elizabeth was behind.

Not only was Elizabeth Garrett-Anderson a doctor and lecturer, she was also a wife, mother of three, author and, in her retirement, became the first woman mayor in England – on 9 November 1908, she was elected to be head of her home town of Aldeburgh. In achieving this position she was following in her father’s footsteps as he, too, had been the mayor of the town in 1889.

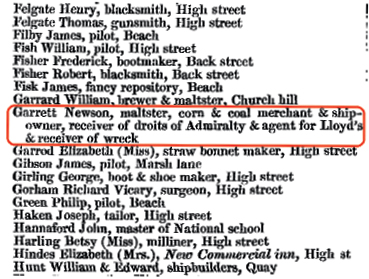

Newson Garrett, Elizabeth’s father, we can see from the 1851 census records had been a corn merchant and by 1871 a justice of the peace as well. The 1855 History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk in the Trade, Residential and Telephone collections on TheGenealogist refers to several new villas having been built in the area, including Newson Garrett’s Alde House in Aldeburgh, presumably constructed as a result of his business success.

The entry in the gazetteer, for the village of Snape, also mentions the hamlet of Snape Bridge. Here it reports there were “commodious wharf and warehouses”. The book describes how “about 17,000 quarters of barley are shipped here yearly for London and other markets by Mr Newson Garrett who has near the Bridge large warehouses, an extensive malting, etc”. Turning to the 1858 Post Office Directory of Suffolk, which lists more of Newson Garrett’s business, we learn that he was also a coal merchant, ship owner, agent for Lloyd’s and more besides.

A particularly useful record set is the National Tithe Records Collection that can be found online at TheGenealogist. With their detailed tithe maps and accompanying apportionment books these records present us with the details of plots of land that our ancestors owned or occupied, mostly in between 1836 and the mid 1850s. Looking for Newson Garrett in these tithe records we can find his business premises at Snape Bridge. The apportionment books detail that he occupied the wharf and various plots including the bridge marsh.

Yet another tithe record result is for his home Alde House where he was both the landowner and occupier. This family home was where, after her parent’s death, Dr Elizabeth Garrett-Anderson and her husband retired and it was where she was living at the time of her becoming the mayor.

No doubt having a successful businessman father gave the young Elizabeth the backing to be able to study what interested her. Marrying a supportive middle-class husband, with means, would have also helped in such an era. But it is her sheer tenacity to become a doctor, against all the barriers put in her way, that should be celebrated in this Women’s History Month. As we should also honour how she opened up the profession to others of her sex by establishing a medical school for women, when they were discouraged from attending the traditional, male-dominated educational establishments. Today it is not unusual for a doctor to be a woman and that is down in no small measure to the path cleared for others by Elizabeth Garrett-Anderson MD.

The Illustrated London News, August 1875

The Medical Directory for 1895 on TheGenealogist

Snape Bridge in the Tithe Records of Suffolk on TheGenealogist

Newson Garrett in the Post Office directory of Suffolk 1858

The Illustrated London News May 18, 1889 on TheGenealogist