Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.A Village Heroine

Nick Thorne traces the family records of a redoubtable Victorian woman, who nursed royalty and many others

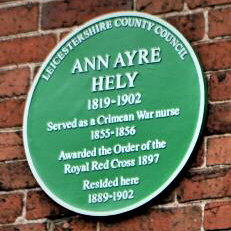

I recently spent a few days in Ravenstone, a small village in the heart of the Leicestershire countryside. Near the sandstone church, that dates from 1323, I was walking past some very old almshouse buildings, set around a pleasant yard, when I saw a green plaque affixed to the red brick wall on the street side. The commemoration was for a past resident of the almshouse, Ann Ayre Hely, a Crimean War nurse.

The Leicestershire County Council website told me more about the person honoured by the green plaque, revealing that its installation at Ravenstone Hospital Almshouses took place only in 2018, 116 years after her death in the very same village in which she had been born.

I also learned that a book had been written by Wendy Freer and published by Pudding Bag Productions (ISBN 9781326888404); from this publication I learned that, after the tragic death of her husband, Ann had answered the call for nurses to travel to Turkey and care for the sick and wounded soldiers of the Crimean War. As someone with practical nursing skills, she travelled first to the hospital in Smyrna and then transferred to the purpose-built Renkioi Hospital, where she remained until the end of the war.

In her old age, while resident at the Ravenstone Hospital Almshouses, Ann was awarded the Royal Red Cross for her nursing services in the Crimean war. Unfortunately, by the time that the honour was to be bestowed, Ann was too frail to make the journey to Windsor Castle to receive it in person from Queen Victoria and so a presentation was arranged to be made in the village by Lady Cave Browne Cave of Rotherwood House, Ashby de la Zouch.

Finding the records

My curiosity was piqued by this tale. Wanting to explore more, when I got back to where I was staying, I thought I’d see what records I could find for her and her family by using the many records on TheGenealogist website.

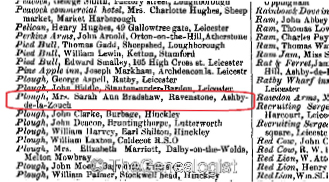

Born in Ravenstone in 1819 as Ann Ayre Bradshaw, the girl who would become the nurse had been the daughter of John, the village blacksmith and his wife, Sarah. When John Bradshaw wasn’t working in his forge, Ann’s father had a second occupation that meant that he was at the heart of the local community – he was the licensed victualler who ran the Plough Inn at Ravenstone. When Ann’s father died in 1838 her mother, Sarah, took over The Plough. This we can find from the census records for 1841 and 1851 on TheGenealogist, as well as John Bradshaw’s death recorded in the Ashby de la Zouch area of Leicestershire in 1838.

Ravenstone Hospital Almshouses

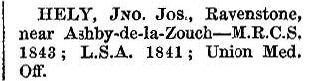

The London & Provincial Medical Directory 1848

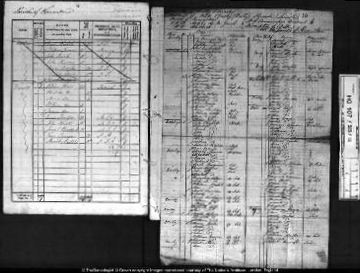

Unusual 1841 census document for a village shared by two counties

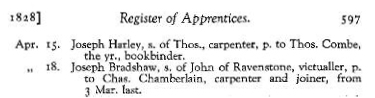

Ann’s brother, Joseph, was apprenticed to a carpenter and joiner according to the Freemen of Leicester records

Sarah Bradshaw, Ann’s sister-in-law in Leicestershire Rutland Post Office Directory, 1876

Curious census document

The 1841 return for Ravenstone is a curious document that is not all on the official form but has an attachment included. At this time the village was shared between two counties, with some households in Derbyshire while the others were in Leicestershire. This confusion means that the enumerator had crossed through homes that were in Derbyshire, but then had added his notes to the remaining Leicestershire returns, listing those homes in Ravenstone which belonged to Derbyshire. The Plough Inn, it would seem from this, was a Derbyshire household at this time.

The 1851 count, however, is more conventional and notes Sarah as a 62-year-old innkeeper, with Ann working in the pub. One of her brothers, Henry, was also listed, perhaps helping his mother and sister at this time.

By 1857, however, Ann’s eldest brother, Thomas, now had charge of the Plough Inn as well as carrying out the local blacksmith business. This detail is provided by a search of the Trade, Residential & Telephone Directories on TheGenealogist and is to be found in the White’s Directory for 1857. Tracing the records further and we can see that Thomas’s wife, confusingly called Mrs Sarah Ann Bradshaw, was still the landlady of The Plough in 1876.

This village pub remained functioning right up to recent times, but sadly it is now closed and awaiting its fate of possible demolition and redevelopment for housing.

While the Bradshaw family had the smithy and the local hostelry businesses sewn up, another one of Ann’s brothers, Joseph, was apprenticed to a carpenter and joiner in 1828. We can tell this from the apprenticeship record pages of the Freemen of Leicester records that are in the Occupational records on TheGenealogist.

From barmaid to professional nurse

The question arises as to how Ann, a rural Leicestershire innkeeper’s daughter, was to become a professional nurse. We know that her value in this service was so appreciated by the authorities that after the Crimean War she went to London to nurse the doyen of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale herself. Ann was then selected to nurse Queen Victoria’s own mother, but Ann never took up this last position as the Duchess of Kent died before Ann could begin nursing her.

The question is possibly answered by the fact that sometime in the 1840s an Irish doctor came to work in the village. The assumption is that, being fond of a drink as reported by the local newspapers, he may have frequented the Plough Inn and so met Ann in the establishment. Whatever the actual facts were, what we can tell from the civil marriage records on TheGenealogist is that the two of them got married in 1851.

Ann’s husband, Dr John Joseph Hely, was nine years older than her, having been born in 1810 in Ireland. He can be found living in Great Titchfield Street, Marylebone in 1841 from a search of the London census records on TheGenealogist. At the time he is recorded as an assistant surgeon and would appear to have been living in the household of a surgeon apothecary. By the time of the next census we can see that he has moved to live in Ravenstone. While he was born in Ireland his qualifications noted in this census, MRCSE, tells us that he was a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh). By continuing to search for the good doctor we then come across an entry in the London & Provincial Medical Directory for 1848 that can be found in the Occupational record sets on TheGenealogist. This reveals that he was a Licentiate of the Apothecaries’ Company (LSA) from 1841 and then obtained the letters MRCS after his name in 1843. This seems to indicate that he had also obtained membership of the Royal College of Surgeons in England, as we already saw in the London census he was a Member of the Edinburgh college when he was recorded in 1841.

The marriage between Ann and the doctor was not destined to be long lived. John Hely died drinking poison after only three years of marriage. Inquests were often convened in the local inn and so it was that the Ravenstone surgeon’s own inquest took place at his in-laws’ pub, The Plough. The verdict of the coroner was that Ann’s husband had got up in the night and mistook colchicum wine for sherry. Evidently the medicine bottle had been broken and it had been decanted into another bottle that the doctor thought contained sherry. Colchicum wine was a medication used in small amounts to treat gout and other conditions, but in large quantities it could be fatal.

Crimean war

With the death of her husband, Ann answered the call of the authorities for nurses to go out to Turkey to look after the men sick and injured in the Crimean War. The newspapers of the time were reporting on the conflict and we can see a piece in an 1855 edition of The Illustrated London News, available on TheGenealogist, that tells of a batch of nurses going out to the area. We are not certain when Ann Hely actually travelled out, but it could have been at this time or earlier in the year.

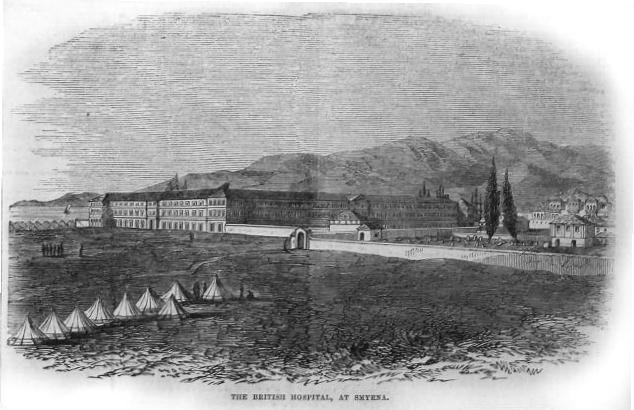

When Ann arrived she was posted to Smyrna Hospital, where diseases such as typhoid, dysentery and cholera were so prevalent that some of the doctors and nurses contracted the infections. This included Ann, though she managed to recover from typhoid while others were not so lucky. The Illustrated London News, from May 1855, published a sketch of the hospital for the benefit of its readers and we can find this by searching TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazine collection.

But in November of that year the military closed the hospital and converted it into barracks for the Swiss Legion. The nurses, including Ann Hely and 115 sick plus 23 wounded patients were transferred in the summer of 1855 to the Dardanelles after the fall of Sevastopol in September. The destination was Renkioi Hospital, where several hundred new patients were also to be looked after.

The new Renkioi Hospital was a pioneering prefabricated building made of wood and designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel to the latest thinking in hospital design. It had much better conditions than the military hospital that they had left and had natural light from large high windows, a good water supply, sanitation and ventilation.

Nursed Florence Nightingale

With the end of the war, Ann returned to England and spent a period of time nursing. It was in this period that she looked after the most famous of all nurses, Florence Nightingale, who often suffered spells that saw her bedridden from illness. After this Ann, aged 42, became the housekeeper to nobility, working for the Earl of Zetland at Aske Hall, Richmond, Yorkshire. When she could no longer work she came home to the village of her birth to live quietly in the Ravenstone Hospital Almshouse and she is resident here in the censuses of 1891 and 1901 on TheGenealogist.

The Plough Inn in 2019, boarded up and awaiting possible demolition and redevelopment

As an old lady, in 1897, she was awarded the Order of the Royal Red Cross and this is noted in a search of the Military records on TheGenealogist where her name appears in the 1901 Army Lists as one of the holders of this order. It is notable that this ordinary village girl, daughter of the blacksmith and innkeeper, was included on a list with the likes of Miss Nightingale, the Queen, other members of the Royal Family, religious sisters from different faiths and the other nurses who had cared for the sick and wounded men from the Crimean war.

The broad range of TheGenealogist’s records has made it easy to find traces of Ann Hely and her kith and kin and so to build the family story of this special woman.

The British Hospital Smyrna, from the 12 May 1855 Illustrated London News at TheGenealogist