Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Anglicans in the archives

Jill Morris looks at the history of the Church of England, and records of clergy available online

Canterbury Cathedral, mother church of the Church of England

The Church of England – now part of the worldwide Anglican Communion – has its origins in Henry VIII’s break from the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s, but has since maintained its position as via media between Catholicism and those Protestant churches that broke away during the seismic changes brought by the Reformation. Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, did not take the title of Supreme Head of the English church, nor did she wish to ‘make windows into men’s souls’ as far as people’s beliefs were concerned. Hence the Anglican Church occupies a middle ground, retaining an ordained clergy and the concept of apostolic succession, yet separate from papal Roman Catholicism.

By the 1700s Anglican clergy – bishops, priests and deacons – had by and large grown lax. Most of the wealthier parishes were held by the wealthier clergy, many of whom had a great deal of political influence. Becoming an ordained member of the priesthood was more often than not seen as a way for aristocratic and influential families to maintain power and land rather than as a calling from God.

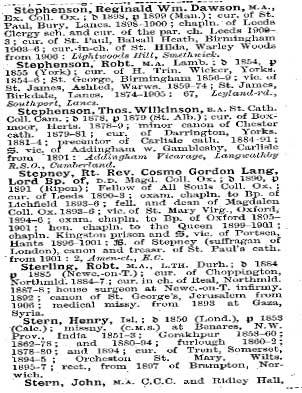

Henry Stern’s record in the 1907 Clergy List at TheGenealogist.co.uk

The social gospel had been all but lost – the plight of the swelling numbers of poor in the burgeoning cities of the Industrial Revolution was ignored. This gaping void was later to be filled by the Methodist movement, with its focus on preaching to those the established Church had left by the wayside. By the 1800s, the Church of England was slowly realising that change was needed, and movements of reform from within its walls saw expansion of the laity and church involvement in some of the most pressing issues of the century, including poverty, health and education.

The Anglican evangelical movements of the 1800s and their appeal to the lower classes had the effect of opening up ordained positions within the Church of England to people from far wider walks of life, and far fewer became absentee landlords. Clergy began to represent broader social spectrum, although not anyone could apply – one still needed an education, and there was a selection process to pass, which included demonstration of a genuine Christian calling. However, many men found that ordination meant his family became upwardly mobile, and it is not unusual to find generations of the same family entering the Anglican ministry. This, and improved 19th-century record keeping, means that if you have ordained Anglican ministers in your family records relating to him and his profession should be accessible (see the case study box).

Made of Stern Stuff

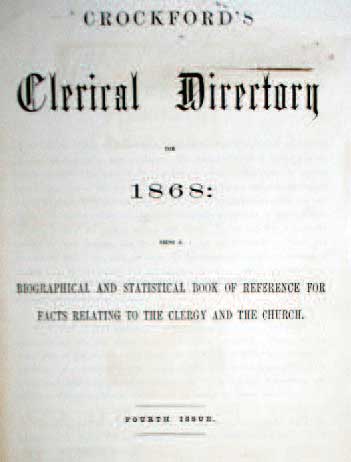

TheGenealogist.co.uk has a number of resources that provide a place from which to start researching ordained Anglican forebears. In addition to the well-known Crockford’s Clerical Directory from 1929 are Clergy Lists from 1852, 1907 and 1911, Index Ecclesiasticus 1800–1840 (alphabetical lists of all ecclesiastical dignitaries in England and Wales) and Manchester records of churchwardens covering almost five centuries, 1422–1911.

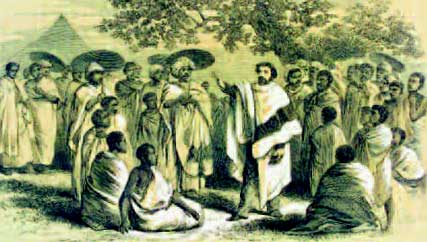

Amongst the records, in the Clergy Lists of 1907, can be found the fascinating Henry Aaron Stern (1820–85). German-born Stern, of Jewish parentage, came to London in 1839 and the following year was baptised into the Anglican Church; he then travelled to Jerusalem – where he was ordained deacon in 1844 – and then to Baghdad as a missionary. The Bishop of London ordained him priest in 1849. Further missionary work took him to Istanbul for six years, and then to Abyssinia, where his unusual career took an even more unusual turn. Stern’s missionary work had focused on Jewish communities, and in 1860 he encountered the Beta Israel or Falasha Jews, a Jewish community that still lives in modern-day Ethiopia. It is still unclear as to how exactly the group reached Ethiopia, but regardless, they had lived there for over two millennia before Stern’s arrival, cut off from any other Jewish communities.

Stern’s book The Captive Missionary recounts his Abyssinian imprisonment from 1863–8. Although the Abyssinian king, Tewodros II, had at first welcomed him and other Europeans, by 1863 his attitude had changed (possibly due to actions of the British Foreign Office). Following an audience with the king, Stern was imprisoned with his assistant. In 1868 the British Expedition to Abyssinia – a rescue mission – was sent to rescue the captives and British government officials and others who had since joined them. Upon his return to England, he captivated audiences with the story of his incarceration.

Henry Stern preaches Christianity to Beta Israel in Abyssinia, a plate from his 1862 book Wanderings Among the Falashas in Abyssinia