Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Banking on fraud

Nick Thorne discovers that a Royal Charter and having MPs for directors failed to stop a Victorian bank embezzling its customers’ money

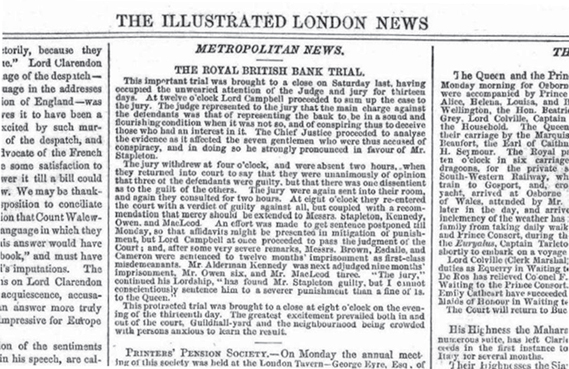

The press being indignant about the failure of a bank, it would seem, is nothing new. In May 1857 the Illustrated London News carried a feature on its front page where it tried to shame the then Attorney General for his “weak and uncertain utterance” about the fraud that the promoters, directors and managers of the Royal British Bank had perpetrated on their clients. The newspaper believed that the people in charge should be prosecuted, that they should appear at the Central Criminal Court and be punished accordingly.

At the time that this opinion was being delivered by the press, the Royal British Bank had appeared in the bankruptcy court on six different accounts ranging from commencing the bank’s business before all the shares had been subscribed and paid up to making large loans to the directors and others.

The bank’s accountant, a Mr Coleman, had to report that the liabilities of the business stood at £539,000 while the assets were £328,000. This would require a call being made on the shareholders to make up the difference and fears were expressed that many would default, leaving the others having to find the difference. But the sum for assets, a report in the Illustrated London News (available in the newspaper and magazine collection on TheGenealogist.co.uk) reveals, may have been overstated. This newspaper report, dated 27 September 1856, asks the rhetorical question as to where the money had gone, and then gives the answer that as soon as the bank was set up and a few accounts opened, the directors and their manager, a Mr Cameron, “set to work appropriating the contents of the till to their own uses”.

The directors, accused of fraud by the gentlemen of the press, were perhaps people who should have known better. Humphrey Brown, Esq, was the MP for Tewkesbury and took out £70,900 from the bank. In comparison the founder of the bank, John MacGregor, Esq, who was the MP for Glasgow, took only £7362 out of his depositors’ funds. What seems incredible is that Mr Hugh Innes Cameron, their general manager, was able to draw £33,000; meanwhile the company’s solicitor drew £7000 and an auditor £2000 from money that was not theirs to take.

Hugh Innes Cameron on the face of it would seem an eminently respectable appointment for an institution requiring trust. From the 1851 census, also on TheGenealogist, we can see that he resided at 1 Hyde Park Gate in Kensington, London though was originally from Scotland. He was recorded, at the date of the census, to be a justice of the peace. This, and other facts, would no doubt have given the depositors in the bank some unfounded reassurance that nothing illegal would be carried out on his watch. If clients of the Royal British Bank, were to enquire even more into Cameron’s background in Scotland, then they would have been still more encouraged. They could have discovered that he had once been the provost (mayor) in his home town of Dingwall in the Highlands, a post he held from 1833 to 1847 (except for 1841). They would find out that he had been a partner in a firm of parliamentary agents and that he had also been elected to be the procurator fiscal for Dingwall in 1835 – this is an important law officer in the Scots legal system where the holder of the office institutes civil and criminal cases for his burgh or shire, and also prosecutes all criminal cases. Surely all this points to a man of integrity?

The bank itself was incorporated by an Act of Parliament, had ‘Royal’ in its name and its founder and another on its board were honourable members of the House of Commons. It was unthinkable that they would be paying themselves dividends out of the deposits of their customers and committing fraud.

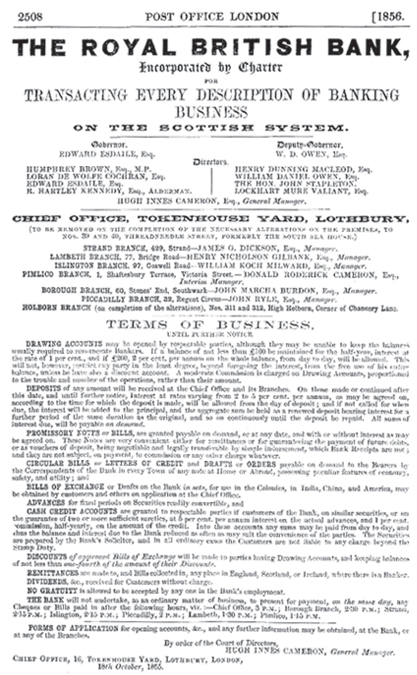

Searching the Trade, Residential and Telephone collection on TheGenealogist for mentions in the directories of the era we come across a full page in the London Post Office Directory for 1856, the very year that browsing The Illustrated London News turns up the reporting of ‘The stoppage of the Royal British Bank’. With the bank’s doors firmly closed, small business people who were its customers were nearly ruined by its failure.

Though his name doesn’t appear on the advertisement found in the trade directory, John MacGregor was the bank’s founder. He had been born in Scotland before his family emigrated to Canada. As a young man he became a merchant on Prince Edward Island and served as High Sheriff for a time and then, in 1824, as a member of the House of Assembly there. Returning to Britain he set up as a commission agent in Liverpool in 1827 before becoming an official at the Board of Trade. On the face of it another respectable citizen and one whom you could trust your savings with.

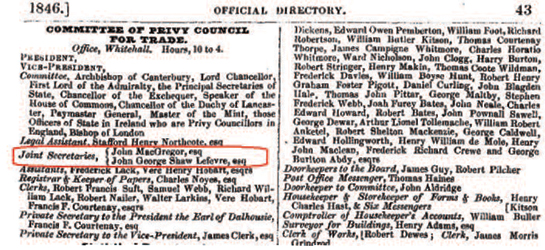

By using the London Post Office Directory for 1846 on TheGenealogist we can confirm his position as one of the joint secretaries to the Committee of Privy Council For Trade, the full name at the time for the Board of Trade. In the court directory of the same publication we are able to discover his address at the time was 3 Lowndes Square and by searching the 1841 census on TheGenealogist we see that he was married to Ann who is shown as being much younger than him. The census of 1841 has rounded their ages to the nearest five years so that he is shown as being 40 and his wife as 25. In the next census they are living in Princes Terrace in Knightsbridge and he is now 54 while she is 38.

The Illustrated London News for 23 May 1857 on TheGenealogist

Advertisement in the Illustrated London News, 21 February 1852

‘The stoppage of the Royal British Bank’ in the Illustrated London News 6 September 1856

The Illustrated London News 1857 on TheGenealogist

London Post Office Directory 1856

London Post Office Directory 1846

Mr Humphrey Brown MP in 1853

In July 1847 he was elected to take his seat as a Liberal member of parliament for Glasgow and he would speak frequently on commercial, financial, and colonial questions. He only resigned his position in 1857, shortly before his death in self imposed exile in Boulogne on 23 April 1857. By his death, MacGregor missed out on his case coming to trial; his colleague on the bank’s board, fellow Liberal politician Humphrey Brown, was not so ‘lucky’.

The honourable member of parliament for Tewkesbury found himself charged with conspiracy to defraud. From the records on TheGenealogist we can see that he too had bolted abroad. In the Illustrated London News for 13 June 1857 we read that a reward had been offered for his apprehension. It was also the first public evidence that the authorities had given that they intended to launch a prosecution of the guilty parties.

When Brown finally stood trial at the Court of Queen’s Bench before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Campbell, and prosecuted by the attorney general, he was found guilty and served six months in prison for the crime. Notwithstanding his fall from grace, after his release he offered himself to the electors of Tewkesbury on two further occasions as their prospective MP. On both occasions the voters declined his offer and in the by election of 1859 he suffered the indignity of polling no votes at all.

The report of the sentencing of the defendants, 6 March 1858 in the Illustrated London News

The trial of the accused fraudsters drew quite some attention. On the first day of the trial the Prince of Wales attended and sat on the bench next to the Lord Chief Justice. In March 1858 the jury found each of the defendants guilty of the charges laid against them, and they were given sentences ranging from a nominal fine of one shilling to imprisonment for up to one year. By July 1858, however, only one of the convicted, the former manager of the bank Hugh Innes Cameron, remained in prison. The collapse gave rise to new legislation tightening banking regulation, including the publication of balance sheets and the auditing of accounts.

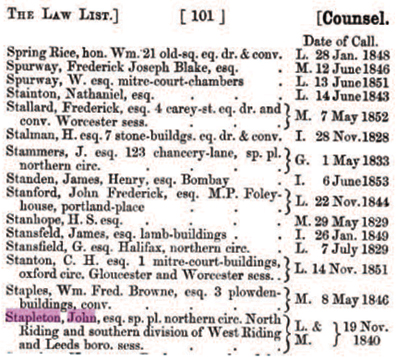

As to the director who was fined just one shilling, that was the Hon John Stapleton. At various times an MP, and a lawyer by profession, he had been called to the bar and practised as a ‘special pleader’ on the northern circuit of the North Riding of Yorkshire and the southern division of West Riding and Leeds. Although he was found guilty with the others, the Lord Chief Justice did not feel able to give him as heavy a sentence as his colleagues. Using the occupational records on TheGenealogist we can find Stapleton’s entry in The Law List of 1856. Quite why he was spared a more severe punishment the reports don’t say.

The records on TheGenealogist have revealed that bank scandals exercised the British Press in the late 1850s and that the presence on the board of a number of worthies is no guarantee of probity.

The Law List 1856 in the occupational records on TheGenealogist