Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Changing names

Nick Thorne unravels a family of name changes and finds a black sheep exiled for his crime

Sir Sampson Gideon who became the 1st Baron Eardley by Pompeo Batoni

As family history researchers we often find people who have a common surname, such as Smith, to be troublesome when investigating a branch of a family tree. Finding them in records is often a problem, especially when the last name is allied with a first name that is also commonplace. Recently I was looking for someone named Smith, but in this case this particular branch of Smiths had seen fit to give their offspring a very distinctive forename of Culling. They then changed their last name to Eardley in 1847 by royal licence, as a result of inheriting an estate that came to them by marriage. A generation on and another union would see the good name of the family dragged through the courts and newspapers.

Born in London in 1805 Sir Culling Eardley Eardley was the 3rd Baronet in his family, his father, Sir Culling Smith, 2nd Baronet (1768–1829), could trace his lineage back to Huguenot stock. At his birth in 1805 the child, who would eventually become the 3rd Baronet, was christened with the name Culling Eardley Smith. It was the death of his maternal grandfather, Lord Eardley, that then brought much of the Eardley estate into the family as his mother, Charlotte Elizabeth (d 15 Sept 1826) was the daughter of Sampson Gideon, 1st Baron Eardley of Spalding. While Lord Eardley had been brought up a Christian, his father was a Jewish City of London banker and confusingly was also named Sampson Gideon.

Changing surnames ran in the family

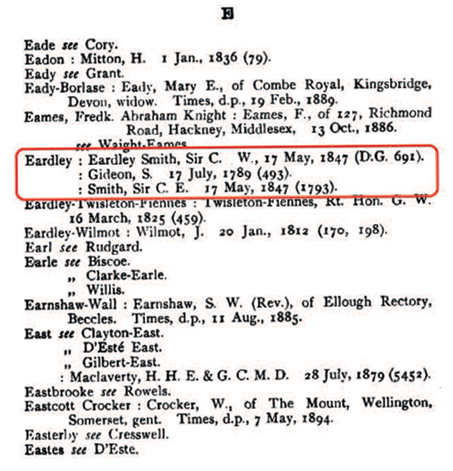

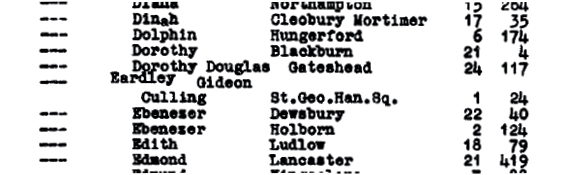

Just as I was getting my notes in order I then discovered that on 17 July 1789 the younger Sampson Gideon legally changed his surname to that of Eardley. So I now had a Smith who took the name Eardley, in honour of his maternal grandfather and who, in turn, had changed his surname to Eardley from previously being known as Gideon. It was clear that changing surnames ran in this family causing confusion for researchers. The Index to Change of Names 1760-1901 for UK and Ireland is about to go live on TheGenealogist and can be used to find someone who changed their surname.

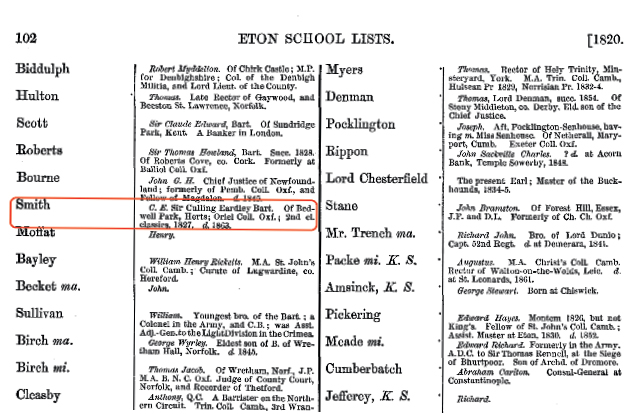

Searching in the Education records, that are on TheGenealogist, finds Sir Culling Eardley Eardley in the Eton School Lists 1820 under the surname Smith and the next column gives his first and middle names as Culling and Eardley.

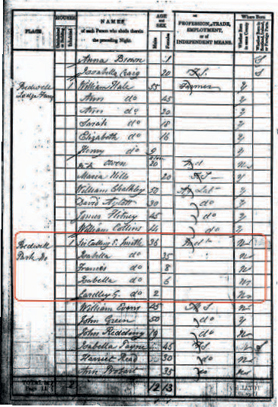

By moving on to take a look at the census records on TheGenealogist for 20 years later I was able to find Sir Culling E Smith, as he was known at the time, in the 1841 census of Hertfordshire. Their address was Bedwell Park in Essendon and this led me to look for an entry for this property in the tithe records.

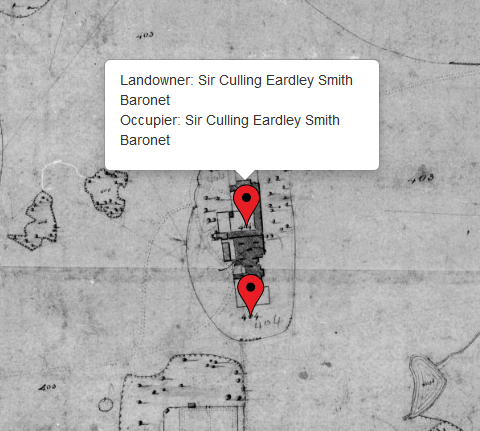

A search of the National Tithe Collection on TheGenealogist finds the estate at Essendon as it was surveyed on the 1838 with land owned and occupied by the Sir Culling Smith as well as that for which he was the landlord and were occupied by other people. The Baronet can be also be found as a landowner in a number of other counties in the tithe collections.

1841 census of Bedwell Park, Essendon, Hertfordshire

Index to Change of Names 1760-1901 for UK and Ireland

Eton School Lists 1820

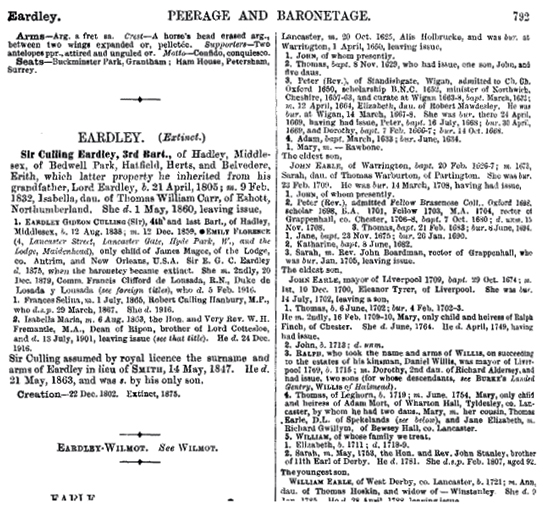

Exploring TheGenealogist’s Peerage, Gentry & Royalty records finds Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage 1921. This resource, lists the estates that Sir Culling still had ownership of after the First World War and he is recorded as being ‘of Hadley, Middlesex; Bedwell Park, Hatfield and Belvedere, Erith’. The last of which, we are told, he had inherited from his grandfather, Lord Eardley.

Burke’s usefully points us to Sir Culling’s children and in particular to his son Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley. His birth was recorded in the General Register Office index and so it can easily be found on TheGenealogist. We may wonder what hopes the family had resting on this son and heir at the time of his delivery? They probably never would have thought that he would grow into an adult that would cause a scandal that would see him summoned before the Justices at Bow Street and sent to trial!

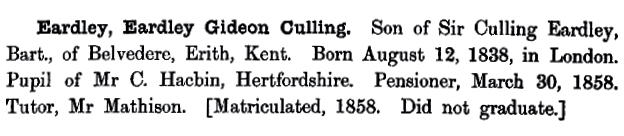

In the Educational records on TheGenealogist we can see that as a young man Eardley was admitted to Trinity College Cambridge and that age twenty he matriculated from that university, but did not graduate.

A search of the Newspaper and Magazines collection, on TheGenealogist, finds both the father and the son get mentioned in The Illustrated London News. While the father appeared for worthily chairing a Christian Evangelical Alliance session, in which they listened to the Canon of Durham request that the Alliance join him in a consultation to reconcile the various denominations of Christianity; the son’s mention in the news, however, was to do with the legality of his marital condition.

Tithe map of Essendon, Hertfordshire 1838, pinpointing Bedwell Park

Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage 1921 on TheGenealogist

Eardley Gideon Culling Smith birth registered in the third quarter of 1838 in St George’s Hanover Square district of London

Trinity College Cambridge Admissions Vol 5 1851-1900

Bigamy

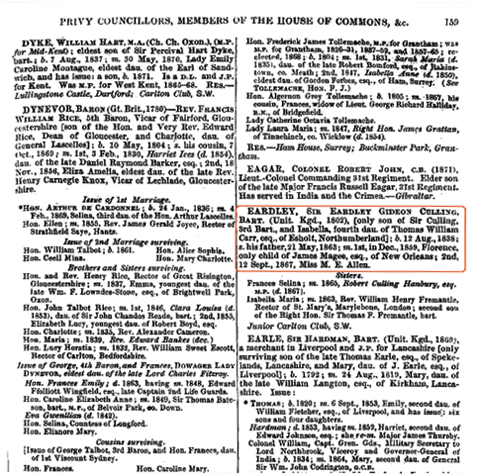

From a quick look at Thom’s British Directory for 1873, on TheGenealogist, in the section on Privy Councilors Sir Eardley’s entry notes the dates of his two marriages as if there is no scandal. One in December 1859 to Florence the only child of James Magee esq of New Orleans and his second union to Miss ME Allen on 12 September 1867.

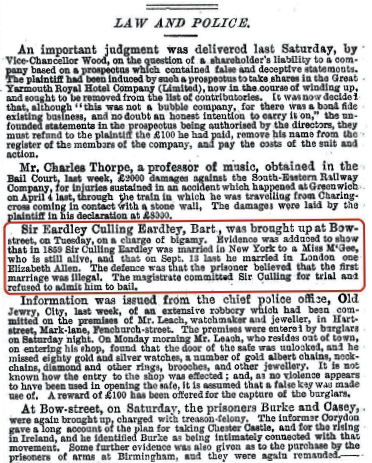

What this doesn’t reveal is that the second wedding, in England, was actually a bigamous marriage as Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley was still married to another! This fact can be discovered by a search for the Eardley name in the newspapers which finds an entry on 14 December 1867 in The Illustrated London News. In this Law and Police report the Baronet, was brought up at Bow Street magistrates court to answer the charge of bigamy. The court was shown evidence that the defendant had married in New York to Miss McGee. Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley was unable to convince the magistrate of his argument and so the prisoner was committed for trial and refused bail for good measure.

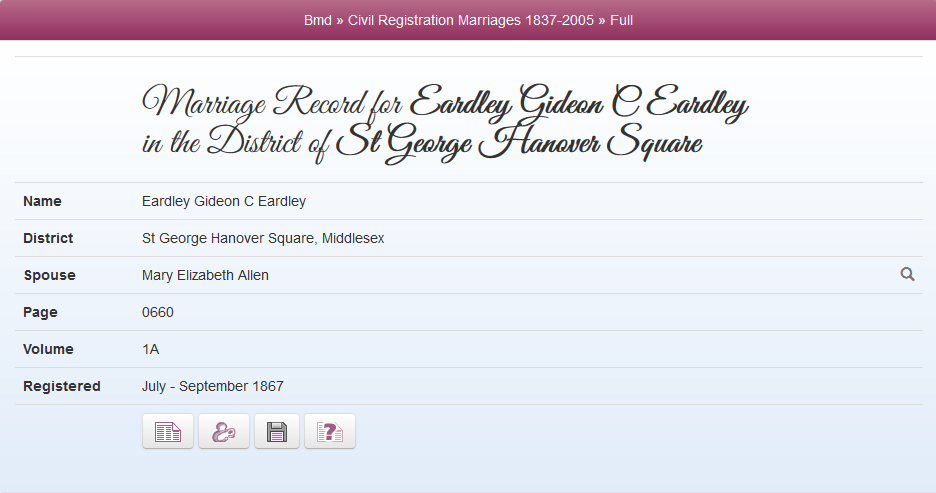

This marriage to Miss McGee was found to be perfectly valid when it came to trial. It does not appear to have been registered in the Consulate records of marriages abroad that can be searched on TheGenealogist as this was not a compulsory requirement. His bigamous marriage in London, however, can be easily located in the GRO index on TheGenealogist. We are able to find it in 1867 in St George Hanover Square, Middlesex.

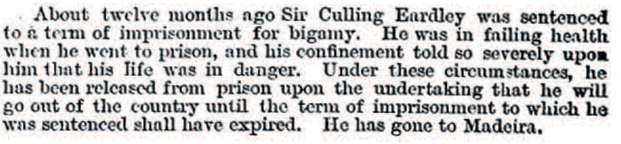

While Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley may have thought that his American marriage was not valid – the courts, however, decided otherwise and sentenced him to eighteen months in prison with hard labour. Further articles appear in the newspapers that publicises that the Baronet found his prison sentence hard to endure with it having a detrimental effect on his health that his life was in danger. A piece in The Illustrated London News on Boxing Day 1868 explains that he was to be released from prison on the understanding that he would exile himself from Britain until his term of imprisonment had been spent. The newspaper noted that he had gone to Madeira. In April of the next year the same paper reported that The Secretary of State had then granted Sir Eardley a free pardon.

The papers, throughout their reporting of the Eardley case seemed to be never very sure what the delinquent baronet’s first name was. In 1867 he is Sir Eardley Gideon Culling Eardley at the start of the paragraph and then Sir Culling Eardley two lines later. In 1869 the same publication, when referring to his free pardon, printed his name as being Sir G Culling Eardley. As with my confusion with the family surname it would seem that the unusual first and middle names bewildered the journalist so that they covered as many versions as they could.

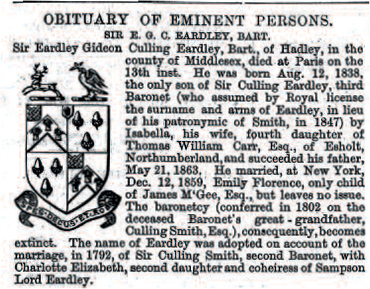

On his death, in 1875, in Paris The Illustrated London News gave him honour of an obituary of an eminent person and correctly printed his full names and the detail of the change by Royal licence of the surname and adoption of the arms of Eardley. Interestingly no mention of his fall from grace, or exile abroad, are made in the obituary and only his legitimate marriage to Emily Florence McGee is referred to.

As a postscript to this case, with his death the Eardley baronetage became extinct. It is not certain from the research what happened to Miss Mary Allen but a search in the Peerage, Gentry & Royalty records on TheGenealogist tells us that his widow, Emily Florence, remarried a Royal Naval Commander. Not just a British naval officer, but one with a foreign aristocratic title as well. Her new husband was Count Francis Clifford De Losada y Lousada, youngest son of the Marquis de Lousada and grandson of a Spanish Duke.

What indeed is in a name?

Thom’s British Directory 1873

The Illustrated London News 14 December 1867

The Illustrated London News 26 December 1868

Marriage 1867 in St George Hanover Square

The Illustrated London News 1875 Obituary of Eminent Persons

Burke’s Dictionary of Peerage & Baronetage 1885 on TheGenealogist