Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Crackers about Christmas

Nick Thorne looks at some of the Victorian people behind Christmas traditions we enjoy to this day

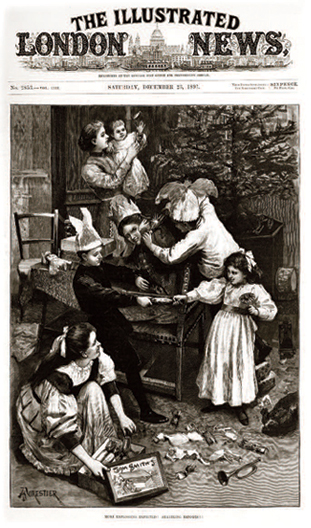

The Illustrated London News 1893

At Christmas time the British dinner table isn’t complete without the ubiquitous Christmas cracker laid at each and every place. The tradition is one that we have to be thankful to our Victorian ancestors for, as crackers were invented by Tom Smith, a name that may still be familiar to revellers today.

Tom, the son of an East Surrey licensed victualler, had started working in a confectioner’s shop in London before he decided to take the plunge and set up his own business. Tom Smith’s confectionery enterprise specialised in sugar decorations, the sort that we still see even today on top of wedding cakes. While on a trip to Paris with his wife in 1844, he came across the bonbon, in which sugar plums were wrapped in a package that closely resembled the cracker that Tom would bring to the British market.

Christmas of that same year saw Tom Smith sell his first bonbons which, with his own twist, contained sugar almonds wrapped in fancy paper. When the festive season was over, however, sales diminished to nothing. Tom Smith reacted to the market conditions by adding a motto, in time to capture Valentine’s day sales. The essential part of a cracker, even to this day, was added in 1846 in the form of the ‘snap’, to make the cracker bang. With the substitution of a ‘surprise’ for the sweets and a coloured label, plus the addition of a paper hat, the Christmas cracker that we would recognise today had been born. The blame for millions of us wearing a paper hat at the Christmas table can be laid firmly at the door of one of Smith’s sons: Walter Smith was the one who suggested including the hat in the crackers that his family made.

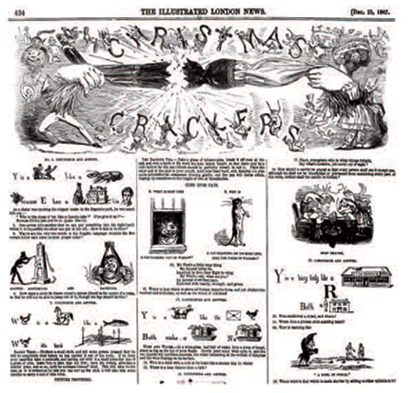

The Illustrated London News 1847

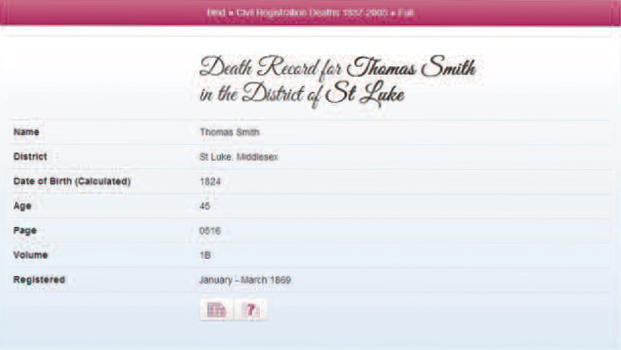

Death of Thomas Smith from the records on TheGenealogist

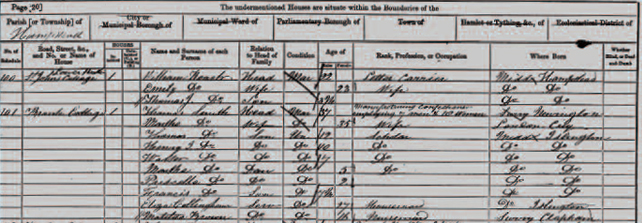

Tom Smith in the 1861 census on TheGenealogist

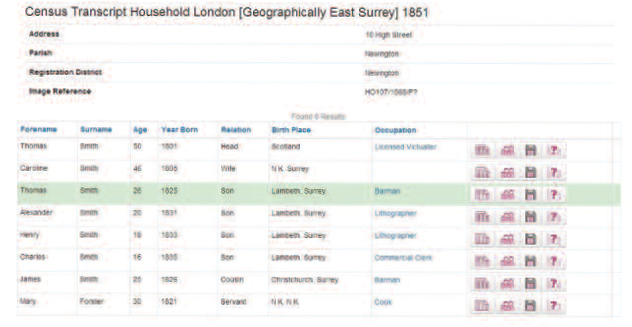

1851 London census transcript

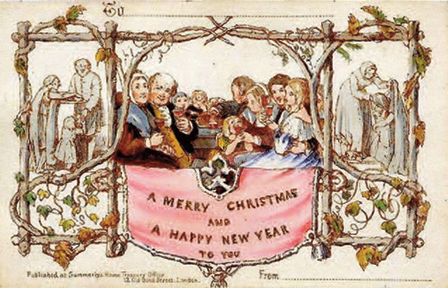

The first commercially produced Christmas card commissioned by Henry Cole 1843

As we can discover, by searching The Illustrated London News on TheGenealogist, by 1847 the concept of a Christmas cracker had become so mainstream that the paper used an illustration of one as a header to a page of Christmas fun.

To find out about the Smith family, a search of the census records on TheGenealogist also reveals more to us about Tom Smith’s business from the details given in the occupation column of the 1861 count. We can see that by this year he had built the business to become the employer of seven men and 18 women.

Tracing Tom himself back to the census that was taken ten years previously, we can see that he was living in his parents’ household at number 10 on the High Street in Newington. His father, also called Thomas Smith, was a licensed victualler in the Newington district of East Surrey. This is an area that would now be considered to be a part of south London. We can see that Tom Smith the younger was working as a barman in 1851 and that his father was born in Scotland.

Tom Smith, the creator of our essential Christmas accessory, did not have a long life: sadly, he was to die in his forties. From our research in the census collections we know that it was sometime before 1871, as Martha and her family are living on their own by this date. To find them is a little more difficult as they have not been recorded as confectioners, or similar occupations, by the enumerator. We are, however, able to use TheGenealogist’s unique family search tool to look for a family group that includes Martha Smith, the mother, and her two eldest sons, Tom and Henry.

This enables us to quickly find Tom’s widow and some of the children, revealing that they had now moved to City Road, in St Luke’s parish, in the Holborn registration district of London. Martha’s occupation is now listed as a clerk and the sons are down as ornament makers. As the family business is known to have passed to them, we can assume that the ornaments that they made were crackers. What is not certain is where the 17-year-old younger brother, Walter, was on census night. The Tom Smith company history reveals that he too joined the business.

To try and find the death of Tom Smith we can use the fact that he had died before the 1871 census and that his wife was living in the Holborn area of London. By carrying out a search of the death records on TheGenealogist using a combination of Tom’s first and surname, plus 1869 (the year that various reports say he died) and then filtering the results with the keyword of 1824 (his date of birth) returns five results. The most likely to chose is the death recorded in the St Luke’s district of London, as this matches the parish recorded for his widow and family some two years later in the 1871 census.

By 1881 Martha, her daughters and son Thomas had moved up to King Henry’s Road in Hampstead.

What would Christmas be without a cracker to pull with its daft motto, surprise gift and paper hat? All these features were the innovations we can thank Tom Smith and his family for.

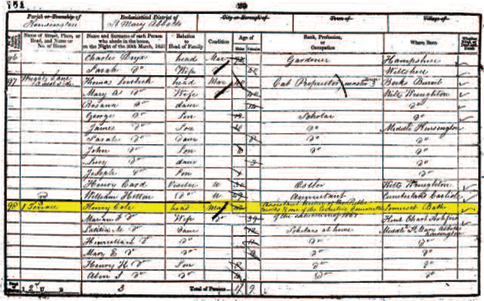

Sir Henry Cole in 1851 census on TheGenealogist

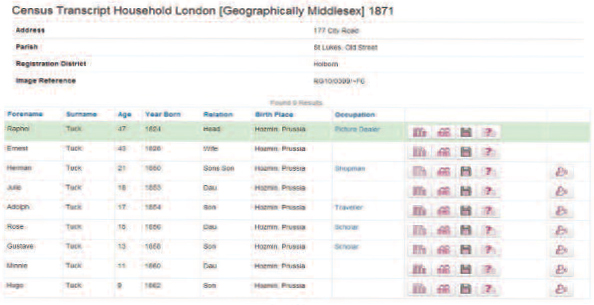

Tuck household in 1871 census on TheGenealogist

Trade directory 1916 on TheGenealogist

Christmas cards

Christmas is also a time for posting greetings to friends and family in the form of a card or two. The first commercially printed Christmas card came out in the mid 19th century when it was introduced by the civil servant and inventor Sir Henry Cole in 1843. He came up with the concept of sending greetings cards at Christmas time and then went on to introduce the world’s first commercial Christmas card in 1843. Cole had already been working with Sir Rowland Hill on the introduction of the penny post a few years previous to this in 1840 and so we can see this idea as a way of encouraging the use of the new service.

Commissioning John Callcott Horsley to design a greeting card, Cole then made them commercially available with a total of 2050 cards being printed and sold for a shilling each. As we can see in the census of 1851, found on TheGenealogist, Sir Henry had gone on to become the Assistant Keeper of the Public Records and one of the Executive Committee of the Exhibition of 1851.

The first Christmas card was not as successful as Cole had perhaps hoped – the temperance league disapproved of it from the point of view that its design would encourage drunkenness. It fell to the German émigré, Raphael Tuck, to later promote a much broader range of cards and also to launch Christian-themed cards into Victorian Britain.

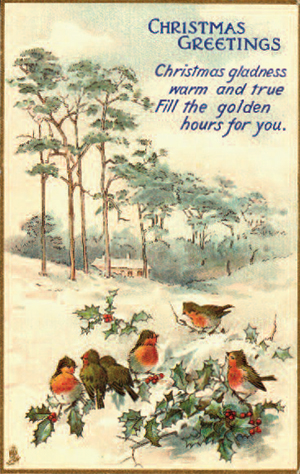

In a little shop in London’s Bishopsgate area, Raphael Tuck and his wife Ernestine set up together a picture business in October 1866 that would have an artistic effect on most of the civilised world. The family were Prussian Jews who had immigrated to Britain with their seven children – four boys and three girls. Their company began selling pictures and greeting cards before expanding to also include postcards. The latter product was to become the most successful of their lines, with their business being best known in the ‘postcard boom’ of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Ironically, as Raphael was a Jew and a respected Talmudic scholar, he would become one of the most important promoters of the Christmas card. Raphael Tuck had noticed that most of the cards sent were mainly secular in design and focused on seasonal revelry such as Sir Henry Cole’s original. Spotting a gap in the market in 1871, Tuck began to supervise the design of a series of religious-themed cards featuring Jesus Christ, the Holy Pair, the Magi, the Nativity scene, as well as the traditional Santa Claus, holly and mistletoe.

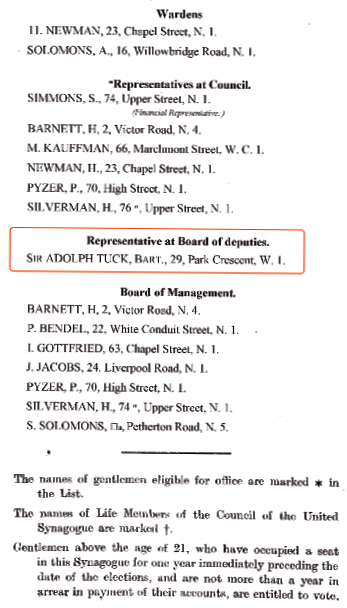

Three out of four of his sons joined the company with the second son, Adolph, eventually becoming the chairman and managing director of Raphael Tuck and Sons Ltd until his death on 3 July 1926.

The Tuck family became very much part of British society. In 1875 Raphael became a naturalised British subject, as we are able to discover from a search of the Overseas, Home Office Naturalisation collection on TheGenealogist, where we discover his certificate numbered A1503 with a date of 30 January 1875. One of Raphael’s sons, Adolph, would be created a baronet on 19 July 1910 and we can find Sir Adolph holding various important positions within the London Jewish community in several of the London synagogue seatholder records that are also on TheGenealogist.

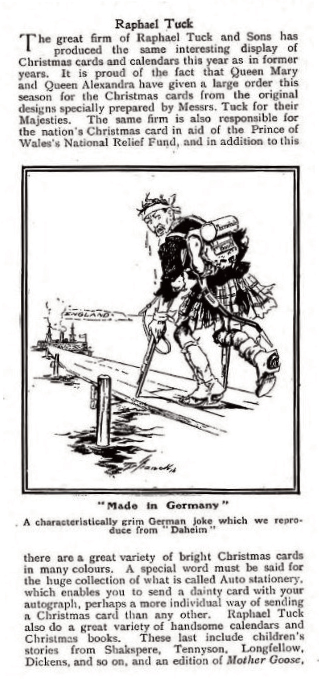

At the time of the Great War, when the land of their birth was at war with Britain, their company was being celebrated as a ‘great firm’ when it was reported in The Sphere magazine of December 1914 that Raphael Tuck & Sons had been given a large order to supply the Christmas cards to Queen Mary and Queen Alexandra.

This carried on a tradition started in 1893 when Queen Victoria had granted the firm the Royal Warrant of Appointment. Tuck’s cards had, from then on in her reign, borne the message ‘Art Publishers to Her Majesty the Queen’, with future sovereigns continuing the warrant of appointment for the business.

Searching the trade directories on TheGenealogist returns several entries for Raphael Tuck & Co including one from 1916 which proudly lists their products as well as their royal connection.

So often we bemoan the commercialisation of Christmas and proclaim how it was so much simpler in days gone by. How many of us, however, would actually want to see Christmas without all these well-established commercial introductions made by these Victorian personalities, whose footprints we have found in the records on TheGenealogist?

A Raphael Tuck Christmas card

Sphere Magazine Issue No. 779, December 26, 1914

London Synagogue Seatholders records on TheGenealogist