Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Dastardly attack on Her Majesty

Nick Thorne investigates the most successful of the numerous attempts to harm Queen Victoria

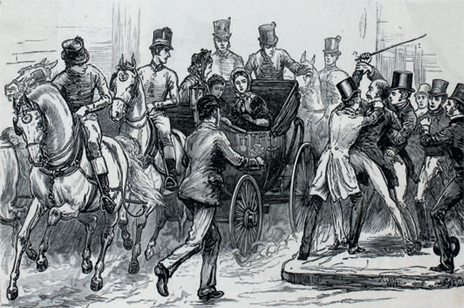

The Illustrated London News March 1882

In July 1850 a former Lieutenant in Queen Victoria’s Army waited outside a large house in London’s Piccadilly, where he knew the monarch to be visiting her mortally ill uncle, Prince Adolphus, The Duke of Cambridge. Robert Pate lingered at the entrance and, as the royal carriage made its way out of Cambridge House’s courtyard, he inexplicably struck the Queen on the head with the brass-topped walking cane that he habitually carried. Onlookers were shocked and immediately restrained him until the police took him into custody.

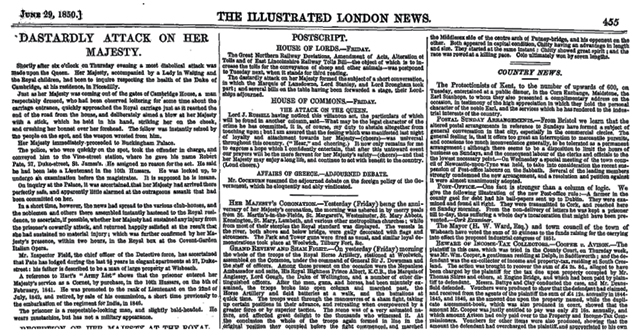

Pate was just one of a number of people who carried out a physical attack on Queen Victoria during her long reign. Others attempted to shoot her, but Pate’s assault with a walking stick was the only one in which she sustained an actual injury, leaving a mark on her forehead for a number of years. The shocking act was recorded in a sketch, within a supplement to The London Illustrated News March 1882, in which it was one of four depictions of violent attacks made on the sovereign. By using TheGenealogist’s Newspaper & Magazine collection I was able to access this supplement, as well as a contemporary report from the same publication dated 29 June 1850. In the latter journal, under a headline of ‘Dastardly Attack on Her Majesty’, the paper explained how Robert Pate had been observed to have been loitering for some time about the carriage entrance to the house.

When an ancestor features in a press story, we may be fortunate to glean certain information that helps us to build a better picture of them, while also gaining clues about the family. In this case we read that Pate was ‘respectably dressed’ and that, on arrival at Vine Street Police Station, he gave his address as 27 Duke Street in the smart area of St James. The head of the detective force had ascertained that Pate had lodged in apartments at that address for the last 2 ½ years and that his father was a landowner from Wisbech in Cambridgeshire.

The same article describes the prisoner as being a “respectable looking man, and slightly baldheaded. He wears mustachios, but has not a military appearance”. The paper tells its readers that Pate “assigned no reason for the attack”, then adds that he said “he had been late a Lieutenant in the 10th Hussars”.

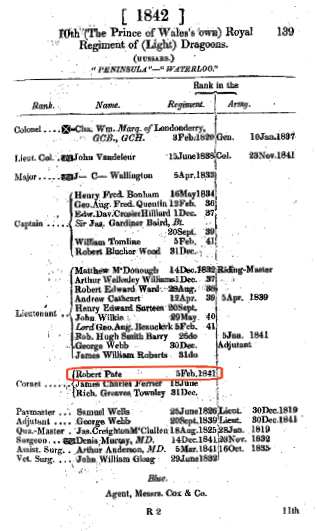

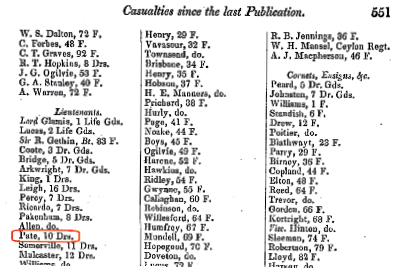

The Illustrated London News resorted to some investigation of its own by turning to Hart’s Army Lists to find out the date Pate entered military service. By using the Military records on TheGenealogist we can mirror this research to corroborate that it was on 5 February 1841 that Pate was commissioned. Another record, from the same collection, shows us that by the publication of the 1847 Army List Lieutenant Pate of the ‘10 Drs’ has been listed as a ‘casualty since the last publication’. He had, in fact, sold his commission in 1846 before his regiment were to embark for service in India and so he probably should have been recorded as a resignation instead. Other accounts suggest that in the years leading up to this event Pate had become increasingly unstable, while still an Army officer.

The Illustrated London News June 29th 1850 - Dastardly Attack on Her Majesty

1842 Army List on TheGenealogist Robert Pate of the 10th Royal Regiment of Light Dragoons

Army list 1847 in TheGenealogist’s Military collection

Family property

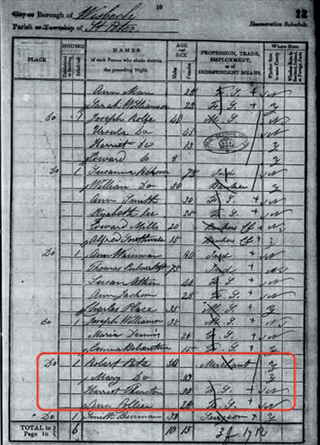

Robert Pate’s commission into the 10th Dragoons had been purchased in the first place by his father. As the newspaper had indicated that Mr Robert Pate Snr was a ‘man of large property’, from Wisbech, I next turned to TheGenealogist’s Landowner records and in particular the national tithe record collection to see if I could identify him. There appeared to be more than one man called Robert Pate in the tithe records for Cambridgeshire but refining the search to Wisbech finds, a Robert Francis Pate there. Now refining my search to include his middle name he can also be found as the landowner of plots in nearby Upwell Cum Welney, which borders with the county of Norfolk. The census for 1841 has Robert Pate Snr recorded as being a merchant living in the North Brink area that ran alongside the River Nene. Browsing back through the images of the census return to the page that contains the enumerator’s schedule, it is possible to read the description of the district. From this we can work out that the family lived in the area known as the Old Market and right in the centre of commercial life of Wisbech.

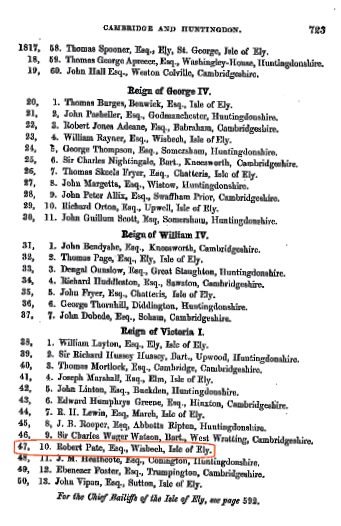

Expanding the search for Robert Pate Snr in TheGenealogist’s Trade, Residential and Telephone directories discovers a list of the High Sheriffs of Cambridgeshire in The History Gazetteer and Directory of Cambridgeshire 1851. Robert Pate Snr, the merchant, had joined the ranks of the gentry by 1847, as can be seen from the dates for the appointments in that publication.

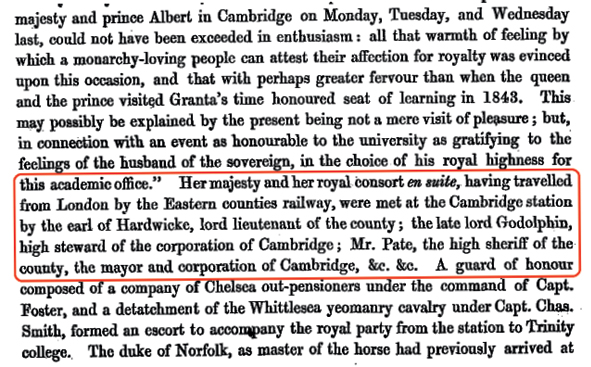

In 1847 Robert Pate Snr, High Sheriff of Cambridgeshire, met the Queen – a more deferential affair than his son’s. Having moved up in society from being a local corn merchant to that of a High Sheriff of his county, Robert Pate Snr was one of the officials whose duty was to meet and greet Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort when they arrived at Cambridge Railway Station on a visit to Trinity College. Presumably the only physical contact would have been to shake the royal hand in a polite and restrained way. The occasion was recorded and appears in The History Gazetteer and Directory of Cambridgeshire 1851 found on TheGenealogist.

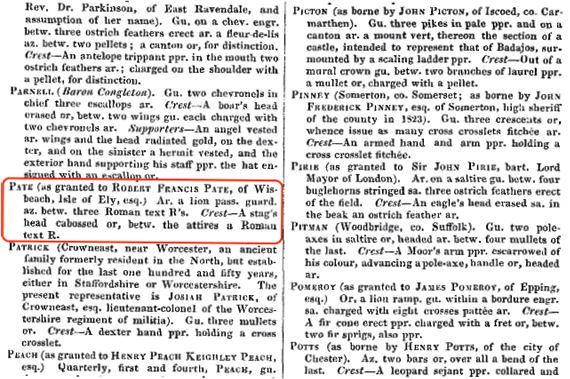

As a High Sheriff Robert Francis Pate now needed a coat of arms and by searching in Burke’s Encyclopaedia of Heraldry for England, Ireland and Scotland part 2 we find a description of the arms granted to him.

In 1856 Robert Pate senior died and it was noted in The Illustrated London News for November 8 1856 that Robert F Pate Esq of Wisbech left an estate of £70,000. Having found this report on TheGenealogist, I could then proceed to check the Wills collection there as well. Pate’s Prerogative Court of Canterbury will reveals sums of money left to his servants and trust funds set up for both his son and daughter.

1841 census Wisbech, Cambridgeshire on TheGenealogist

Mr Pate the high sheriff meets the Queen and Prince Albert from the train in 1847 - The History Gazetteer and Directory of Cambridgeshire 1851

Burke’s Encyclopaedia of Heraldry for England, Ireland and Scotland part 2

High Sheriffs of Cambs in The History Gazetteer and Directory of Cambridgeshire 1851

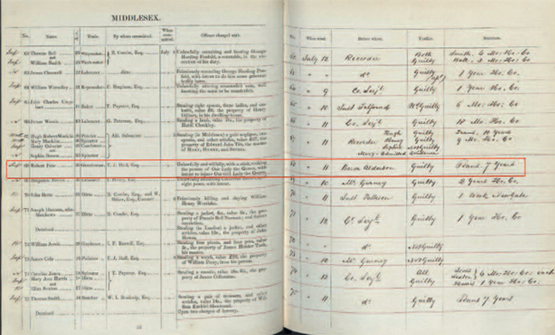

The verdict and the outcome in the Court & Criminal records

The death of Robert Pate Snr took place six years after his son’s crime and so he was alive at the time the case went to trial. To find out what sentence Pate Jr received, I turned to the Court & Criminal records on TheGenealogist and in particular the Newgate Prison Calendar for the 11th July 1850. This record reveals that on the 11th July 1850 he was found guilty and handed down a sentence of 7 years transportation. A further record in this set shows us that he was held in Millbank prison while awaiting his transportation to Van Diemen's Land in Australia.

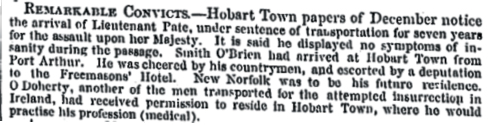

By then turning back to the Newspaper collection finds a short piece that gives the details of the arrival in Hobart of what the paper calls some ‘Remarkable Convicts’ – one of which is our Lieutenant Pate.

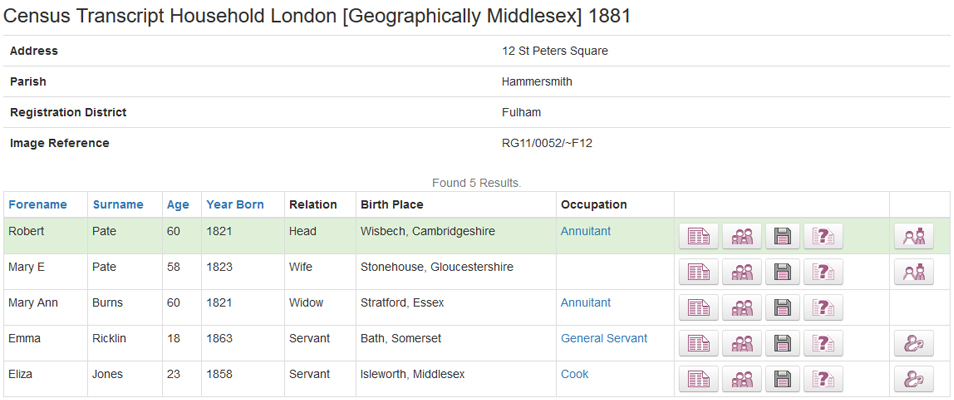

Pate served his full term in the penal colony and on his release he married Mary Elizabeth Brown in Tasmania. Unlike many ancestors transported to Australia, who were too poor to pay for a passage home and had to remain there whether they liked it or not, Pate and his new wife were able to return to England. We are able to use the 1881 census on TheGenealogist to find them living at 12 St Peter’s Square in Hammersmith, London. From this we can see that Mary Ann had also been born in England at Stonehouse in Gloucestershire.

Some time in the 1880s Robert Pate and his wife then moved to south London and so his death is found in the records on TheGenealogist in the first quarter of 1895 in the Croydon area.

While we may not have ancestors who achieved notoriety by hitting the reigning monarch over the head with a stick, the wide range of records available to subscribers of TheGenealogist allows researchers to dig deeper into their own past family members’ story to discover more.

Robert Francis Pate’s Prerogative Court of Canterbury will 1856

Newgate Prison Calendar, folio 24 in the Court & Criminal records on TheGenealogist

Robert Pate Junior in the 1881 census of London

The Illustrated London News April 19 1851 - Remarkable Convicts.

Newgate Prison Calendar 11th July 1850 on TheGenealogist