Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.‘For the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil’

Nick Thorne investigates the story of the Reverend Vyvyan Moyle and his temptations of the monetary kind

The Reverend Vyvyan Henry Moyle was born in Penzance Cornwall in 1834 to a well-heeled family. After matriculating from Oxford in 1853, he became a priest in the Church of England and made a good marriage to Wilhelmina Elizabeth Wade.

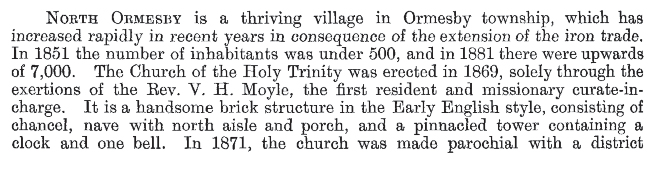

As a vicar he was reported to be well liked in his parish in Yorkshire. From the 1890 edition of Bulmer’s North Yorkshire Directory, available within TheGenealogist’s Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories collection, we read that he was solely responsible for the building of the Church of the Holy Trinity in North Ormesby in 1869. Turning the page of this directory we find that the living was worth £300 a year, but that the church was by then in the care of another vicar – perhaps not a surprise as 20 years had passed.

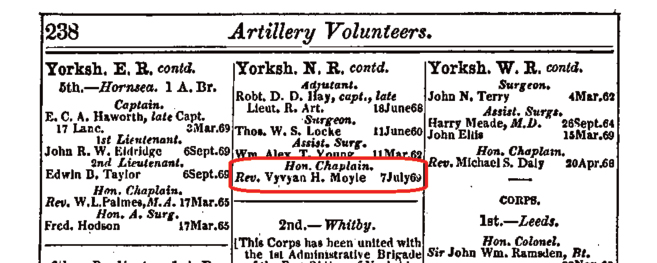

By searching the military records on TheGenealogist we find that he had been recorded in 1870 in The Army List as the Honorary Chaplain to the 1st North Riding of Yorkshire Volunteer Artillery in Guisborough.

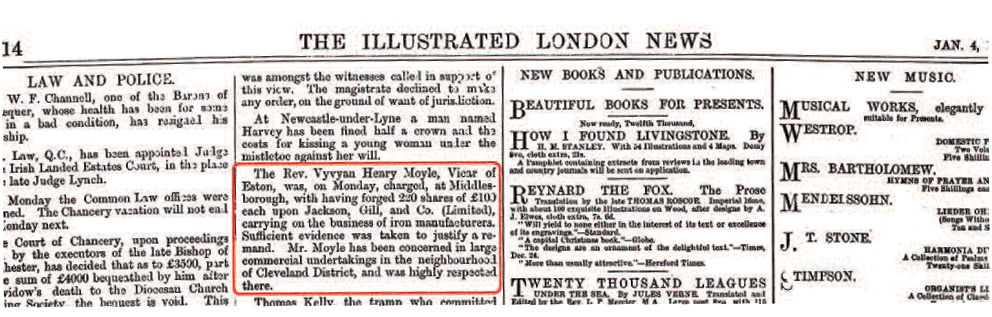

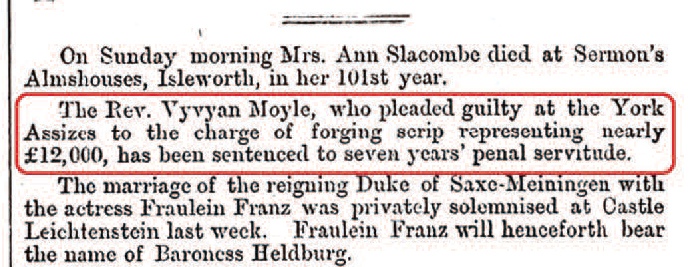

The respectable Reverend Moyle, however, had another side – one which his parishioners must have been surprised to have discovered. He had been tempted by the chance to make some money, even if it wasn’t in a legal manner. From a report in The Illustrated London News in 1873, discovered from a search within the Newspaper and Magazine collections on TheGenealogist, we find that the law had caught up with him. Just four years after the erection of the church at Ormesby, and while he was still in holy orders as the vicar of Eston, he was charged at Middlesbrough with the forging of 220 shares at £100 each in an iron manufacturers’ business called Jackson, Gill and Co. The evidence presented before the court was sufficiently grave enough for him to be remanded in custody.

Taken before the magistrates

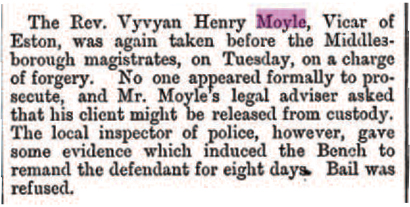

A few days later, another piece in the papers revealed that he was once more before the magistrates. This appearance was in order that his legal adviser could request for him to be released from custody. At that time no one appeared formally for the prosecution but the local police inspector gave some evidence that induced the bench to remand him in custody for another eight days and they refused bail.

After his sentence had been served it would seem that the clergyman thought that a move from the north to the south of the country was preferable and it seems that a bishop, on charitably accepting that Moyle was a repentant man, appointed him to be the vicar of a Berkshire parish.

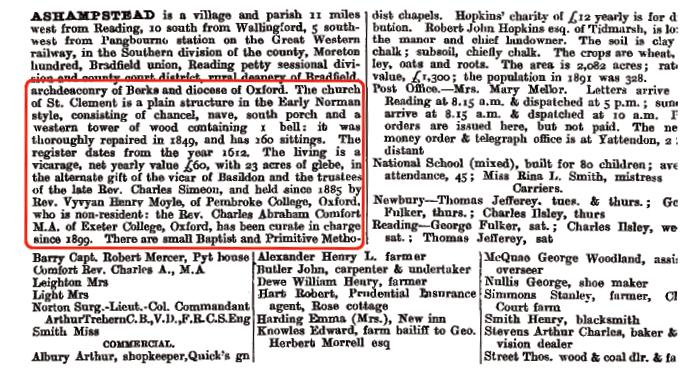

Unfortunately not all was well. If we read Kelly’s Directory of Berkshire 1899 we can see how it passes over the absence of the Vicar of Ashampstead, some nine miles away from Reading, by simply saying that he “is non resident”.

What it doesn’t reveal is that the Rev Moyle had been declared bankrupt by Reading County Court with the receiving order made on 3 November, 1894, the adjudication followed on 14 November and the statement of affairs filed on 18 December, 1894.

This showed a gross liability of £625 against Moyle’s assets of just 16 shillings. This state of affairs would surface once again in yet another appearance that the clergyman made in a court of law, in 1905, when the jury would be told that he was still an undischarged bankrupt at that time.

Living apart

In the 1881 census we are able to find Moyle and his family living in Burghfield, Buckinghamshire. His wife Wilhelmina and his son were with him at that time; but by 1891 they appear to be now living apart. He is in Ashampstead, where his parish was situated, and is recorded as the head of a house that includes just him and his widowed cousin. We may wonder if this older lady is acting as his housekeeper as Wilhelmina Moyle is now recorded to be the head of the household at a Bexhill address that is approximately 130 miles away on the Sussex coast and where she is living with their children.

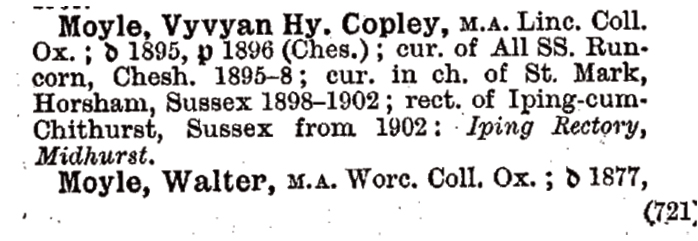

By 1901 Wilhelmina is now at Horsham, West Sussex, residing in the house of her 28 year old son, the Rev Henry Copley Moyle, a Church of England clergyman like his father. Also under this roof is Henry’s sister, which certainly points to there having been a split in the family. Meanwhile the Rev Vyvyan Moyle is now 67 and, together with his 82-year-old cousin, is living in Wood Green in North London. These living arrangements make us wonder if they are as a result of the disgrace the Rev Vyvyan Moyle had brought to the family.

Was the clergyman repentant, as his bishop had hoped on appointing him to his new parish? Had Vyvyan Moyle changed his ways? The evidence would seem to point to him lapsing into sin and forgetting the commandment that ‘Thou shalt not steal’. In 1905 we find him as a defendant in court once again – this time as an accomplice to a fraudster in promoting to the public shares in a bogus company called the ‘South and South West Coast Steam Trawling and Fishing Syndicate’. The confidence tricksters had promised investors that their money would be secured against a “first-class vessel”. The truth was that the boat was worthless, sinking on her moorings on the River Mersey.

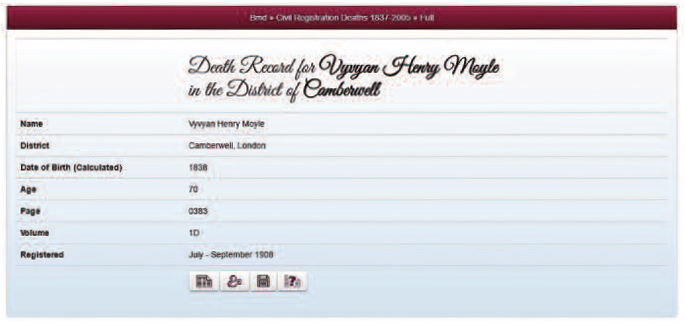

Moyle was found guilty and sent to prison to serve 18 months’ hard labour. Presumably this was a difficult sentence for the elderly clergyman to endure. On release from his incarceration his life was approaching its end. As can be seen from a search of the death records on TheGenealogist for the third quarter of 1908, three years after his 1905 conviction the errant reverend went to meet his maker.

A search of the previous year’s Crockford’s Clerical Dictionary, from TheGenealogist’s Occupational records, finds only his son the Reverend Vyvyan Henry Copley Moyle listed for 1907. Presumably the Rev Moyle Senior was not now deemed worthy of mention in the publication. We have to wonder just how the Rector of Iping’s wayward father, and his fall from grace, must have caused the gossips’ tongues to wag in this Sussex parish.

1890 Bulmer’s North Yorkshire Directory

The Army List April, 1870 from TheGenealogist’s Military records

The Illustrated London News 4 January, 1873

The Illustrated London News 11 January 1873 on TheGenealogist

The Illustrated London News 29 March 1873

Kelly’s Directory of Berkshire 1899

The Rev Vyvyan Moyle’s death record from 1908

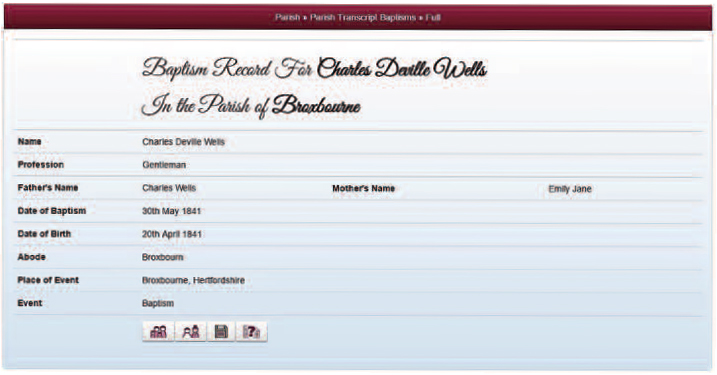

Charles Deville Wells’s baptism record from 1841

The man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo

And what of Moyle’s co-accused? At the time of the trial he was using the alias of William Devenport. He was quickly identified by a clerk of the bankruptcy court, however, to be an undischarged bankrupt by the name of Charles Deville Wells. Wells’s main claim to fame was that, as a gambler, he had managed to break the bank at the Monte Carlo Casino when he won a million francs at the roulette table in 1891. With the money he had purchased a large yacht and had her refitted with lavish accommodation that also included a ballroom large enough for 50 guests. After his initial wins at the casino he returned to Monte Carlo again in January 1892, but this time he lost about 100,000 francs.

Meanwhile, he had set about swindling others out of money by getting them to invest in various ventures. Moving to and fro between France and England he had set up a number of fraudulent schemes. These included getting people in England to invest in the patents for inventions that he claimed that he had invented. In France he touted for investors in a nonexistent railway, disappearing with their money; he set up a Paris Bank, where existing customers were paid out of the funds provided by the new investors and, back in England, he promoted the sale of shares in the bogus company called the South and South West Coast Steam Trawling and Fishing Syndicate. It was this venture in which the Rev Moyle added a touch of respectability to convince the investors all was well. For the man who had broken the bank at Monte Carlo, by 1903 Wells had fallen on hard times. He had been adjudicated bankrupt in England, with liabilities of £978 7s 10d with not a penny in dividends having been paid to the creditors by the time of the fraud trial.

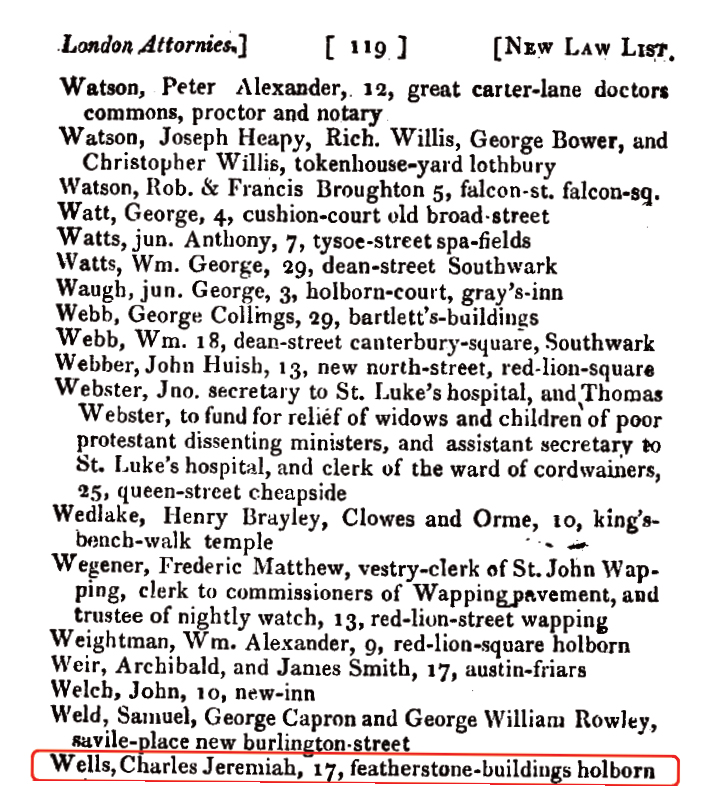

Charles Deville Wells (1841–1922) was the son of lawyer and poet Charles Jeremiah Wells, whom we can find in the 1824 Law Lists available on TheGenealogist.

Charles De Ville Wells was born in Broxbourne, Hertfordshire and, by searching the parish records for Broxbourne in May 1841 (again available on TheGenealogist), we find that he had been born on 20 April 1841. His mother was Emily Jane Hill, the daughter of a Hertfordshire schoolteacher and the young Charles was their only son and the last of their four surviving children to be born. When he was a few weeks old the whole family moved from their home in England, to France, where they lived initially at Quimper, and then later on at Marseille. This background began his ability to move easily between the two countries, though quite why he turned to white collar crime is anyone’s guess. It is thought that Wells died with no money in Paris around 1922.

The well-liked vicar and the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo made for an unlikely pairing – but both flawed men were fraudsters who served a prison sentence more than once, not learning their lesson from being caught and punished by the authorities.

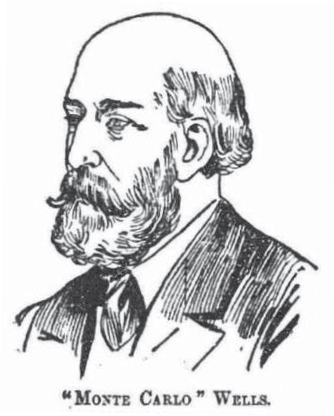

Moyle’s associate Charles Deville Wells, ‘the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo’

Charles Jeremiah Wells in New Law List 1824 from TheGenealogist's Occupational records

1907 Crockford’s Clerical Dictionary, from TheGenealogist’s Occupational records

Wells’s steam yacht Palais Royal (formerly Tycho Brahe)

Wells’s exploits were immortalised in a music hall song by Fred Gilbert