Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Gather ye Records while ye May!

Nick Thorne finds out about the Herricks of Leicester

Leicester Cathedral

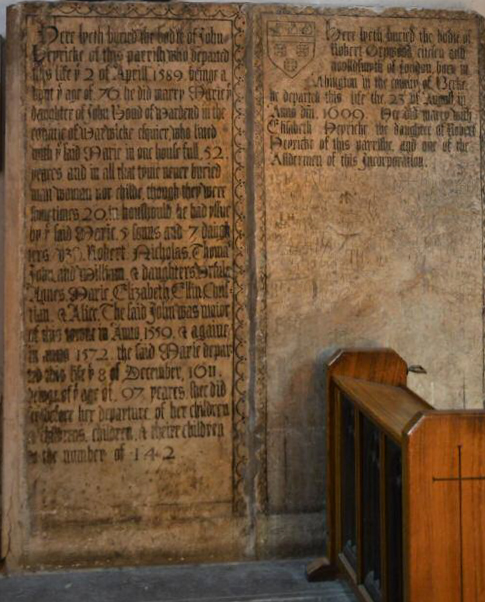

Monuments to members of the Herrick family surrounding the walls of St Katherine’s Chapel while some are buried under foot

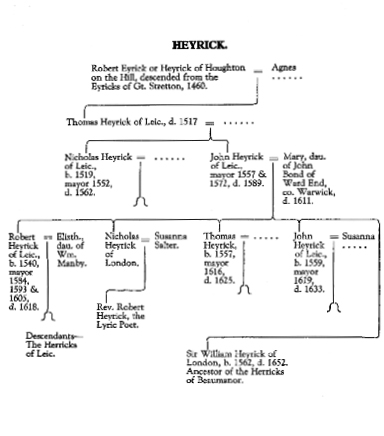

Roll of the Mayors of the Borough and Lord Mayors of the City of Leicester 1209–1935 from TheGenealogist

Robert Heyrick, mayor 1584, 1593 and 1605 and MP 1588

Dropping into Leicester Cathedral recently to take a look at the tomb of Richard III, I listened to the guide retell the amazing story about how the 15th century king had been found under the letter ‘R’ in the car park of a council building.

The cathedral itself had for many years been the parish church of St Martin’s, only in 1926 becoming the seat of the Bishop of Leicester. Close neighbours to the Guildhall, many civic dignitaries are therefore buried under its floor. To the left of the 2016 tomb of the last king of the House of York is a small side chapel dedicated to Saint Katherine. Above its altar is a stained glass window split into three images, the centre of which depicts the unfortunate saint who was said to have been tortured on a wheel before being decapitated. The right-hand panel depicts the distinctively hooked-nosed English Cavalier poet and cleric Robert Herrick, responsible for the poem entitled ‘To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time’. This composition is most famous for the first line of its first verse:

Gather ye Rose-buds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying:

And this same flower that smiles to-day,

To-morrow will be dying.

Robert Herrick’s theme of carpe diem recognises the brevity of life and, therefore, the need to live for and in the moment. It reminds us all that there is no time to lose. Perhaps we should remember this in our quest to gather our family records before it is too late?

The Rev. Robert Herrick was born in 1591 in Cheapside, London, the seventh child and fourth son of Julia Stone and Nicholas Herrick, a prosperous goldsmith in London originally from Leicester. Saint Katherine’s chapel in Leicester Cathedral has many monuments to the Herrick family. Visitors passing through, on their way to see the resting place of the last Plantagenet King, are compelled to walk over the graves of the Herricks, many of whom had served as aldermen, mayors and MPs for Leicester.

One of these graves is for the poet Robert’s uncle, Sir William Herrick (or Heyrick). He was a prosperous goldsmith, MP for Leicester and the principal jeweller to King James VI/I. By a twist of fate Sir William had bought the land that Greyfriars Friary had once stood on and had built a house there. The 2016 reburial of the king has now brought these two men to be yards away from each once more.

Leaving the cathedral I turned down the narrow lane dividing St Martin’s from the ancient Guildhall. The timber-framed building that is now a museum owned by Leicester City Council and can trace its history back to 1390, contains the mayor’s parlour and here I came face to face with two portraits of Herrick family members, Sir William and his older brother John.

In 1600, Sir William Herrick was elected member of parliament for Leicester and again in 1605 and 1620 according to the frame around his picture, though the History of Parliament gives the dates as 1601, 1604 and 1621. As principle jeweller to King James, Anne of Denmark and Prince Henry from 1603 until 1625, Herrick had become a freeman of the City of London in May 1605 and was knighted in the same year for skilfully making a hole in a great diamond that King James liked to wear. Sir William also held the position of prime warden of the Goldsmiths’ Company from 1605 to 1606 and lived to the age of about 90.

To find out more, a search of the Polls and Electoral Rolls records on TheGenealogist quickly returned a family pedigree from Roll of the Mayors of the Borough and Lord Mayors of the City of Leicester 1209–1935.

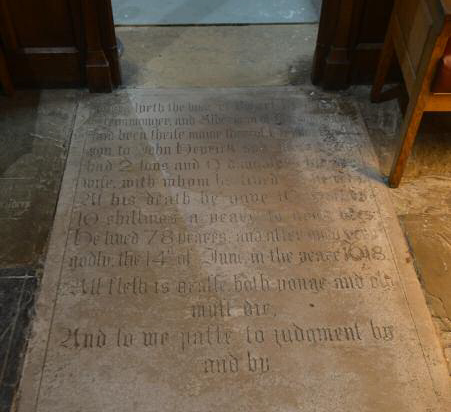

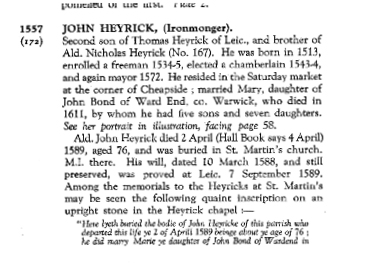

Further searches within this same record on TheGenealogist gives us an entry for each mayor of the borough from 1209. Reading John Heyrick’s, 1513–1588, we learn that he was an ironmonger. From the pedigree we see he was the father of the two men whose portraits I had seen in the Guildhall. As well as telling us about the man, it reproduces the inscription on an upright stone in St Katherine’s Chapel. This monument had caught my eye in the cathedral and I had photographed it myself on my visit. If I had any trouble deciphering the actual stone then the reproduction of the inscription in the records that I had found on TheGenealogist reveals that John Heyrick and his wife Marie (Mary) lived in one house for 52 years.

'And in all that tyme never buried man, woman nor child, though there were sometimes 20 in household...'

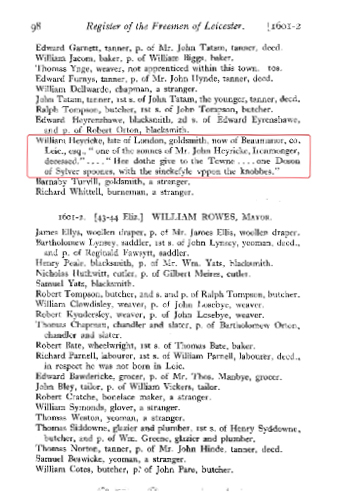

The Occupational records on TheGenealogist also include a listing of the Freemen of Leicester that stretches back as far as the year 1196 and features several family members, but with variations in the spelling of their surnames. William Heyricke, it would appear from the record of freemen, was first admitted in 1601 and draws our attention to another property that he owned in Leicestershire called Beaumanor. As a gift to the town the wealthy goldsmith had donated one dozen silver spoons instead of a fee, ‘with the sinckefyle upon the knobbes’ (Leicester borough arms include a cinquefoil heraldic design).

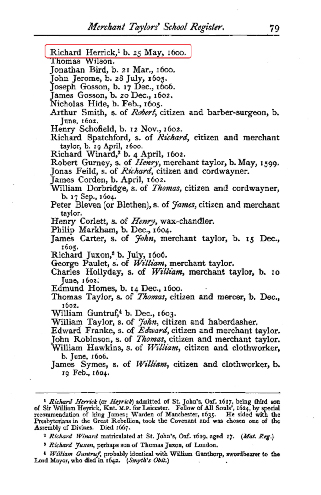

The year before he became a Freeman of Leicester Sir William’s wife, Joan, had given birth to a third son named Richard. By using the educational records on TheGenealogist we see that they sent him to the Merchant Taylors’ School in Middlesex and it is here that another of their seven sons, Roger, also attended for a time – though he is also recorded in those of the Old Westminsters indicating that he went to Westminster School as well.

Another document that provides copious information about Sir William is his entry in The Dictionary of National Biography also to be found on TheGenealogist under its Occupational records. This provides us details such as that Sir William was not only a goldsmith but also a moneylender; that he was the fifth son of John Hericke or Herrick and that the surname is also spelt Heyrick and Eyricke. With this evidence and the various spellings of the name in the Freeman records we see just how fluid last names were at this time. We are told that his mother was named Mary and that she was the daughter of John Bond of Ward End, otherwise Little Bromwich in Warwickshire. We also learn that about 1562 William had been apprenticed to his elder brother, Nicholas, who was already a goldsmith at Cheapside in the City of London. This was the father of Robert the poet who is immortalised in the window at the cathedral in Leicester.

The account tells us also of Sir William’s royal patronage, going on a mission for Queen Elizabeth I to the Grand Turk. Apart from becoming James I’s principal jeweller, he also lent the king vast amounts of money, causing Sir William financial difficulty for a time, though later King James granted liberal awards of land in various counties and towns to Sir William. On Charles I’s accession to the throne, however, he was out of favour and lost his position as the king’s principal jeweller.

With the death of his elder brother, Nicholas, Sir William became the guardian of his brother’s children including Robert, who we can read more about in his own entry in The Dictionary of National Biography on TheGenealogist. This nephew became apprenticed to the jeweller but didn’t serve out his time, going up to Cambridge University instead and was supported financially by Sir William. Robert’s entry in the biography reveals that his father had died by falling out of a window in his own house. As suicide was suspected, the Bishop of Bristol laid claim to all of Nicholas’s goods and chattels but, after arbitration, eventually settled for a sum of money.

My visit to Leicester Cathedral to see Richard III’s grave had me sidetracked by the story of those Herricks buried in its side chapel. It set me off delving into records on TheGenealogist that took me way back into Tudor and Jacobean times and successfully finding out more about the MP who had built a house on the site of Richard III’s grave. I discovered he had once been a royal jeweller and had looked after his brother’s children including the poet responsible for those famous words encouraging us all not to put things off: ‘Gather ye Rose-buds while ye may.’ And this should remind us all not to delay what we can do today... including our research!

The tomb of Richard III in Leicester Cathedral

Robert Herrick, ironmonger and alderman buried under the entrance to the chapel

The mayor’s parlour and seat, Leicester Guildhall

Sir William Heyrick, MP for Leicester on three occasions

John Heyrick in Roll of the Mayors of the Borough and Lord Mayors of the City of Leicester 1209–1935

Window in St Katherine’s Chapel, Leicester Cathedral depicting the poet Robert Herrick

Upright stone memorial to John Heyrick quoted in the record Roll of the Mayors of the Borough and Lord Mayors of the City of Leicester 1209–1935

William Heyricke in 1601 from TheGenealogist’s Occupational records, Freemen of Leicester 1196–1770

Richard Herrick in the Educational records on TheGenealogist