Your Family Tree

Your Family Tree is a leading family history magazine available from all good newsagents. Click here to subscribe.In service - from simple house to palace

Your servant ancestors worked in all sorts of places, from palaces to terraced houses, says Nick Thorne

In the last ever series of the popular TV show Downton Abbey, there had been a theme of facing up to the financial reality of the new order and reducing the number of servants in the household. The drama had reached the 1920s, and the butler, Carson, informed Lord Grantham that another maid had handed in her notice as the fixed hours of shop work were preferable to longer hours in the house. The story reflected what had been happening with many of our ancestors who were in domestic service in post World War 1 Britain, with the lure of other work drawing them away.

At the time of the 1851 census, there were more than one million people in domestic service in England and Wales. This figure was exceeded only by those who were employed as agricultural labourers, farm servants or shepherds. Throughout subsequent census years the numbers working as servants rise, but by 1911 they were starting to reduce, despite the fact that the population was increasing.

DISMISSED WITHOUT WARNING

A domestic servant worked long hours. Whilst they would be provided with accommodation, in return the servant was expected to give up their whole time to their master or mistress and obey their lawful instructions relating to their employment. In some cases, the relationship between servant and master may have broken down and there were certainly instances where a servant was dismissed without warning.

A servant could be sacked for gross immoral conduct; for wilfully misappropriating their master or mistress's property; or for wilful disobedience. There is a law case from 1800 where a servant asked permission to be absent from their master's house for a night, in order to visit their sick mother. Their request was refused, as their employer could not do without their presence in the house overnight. The servant absented themselves anyway. When it reached court, the verdict was in the employer's favour - as the servant had disobeyed their master's lawful orders in the regular course of their employment.

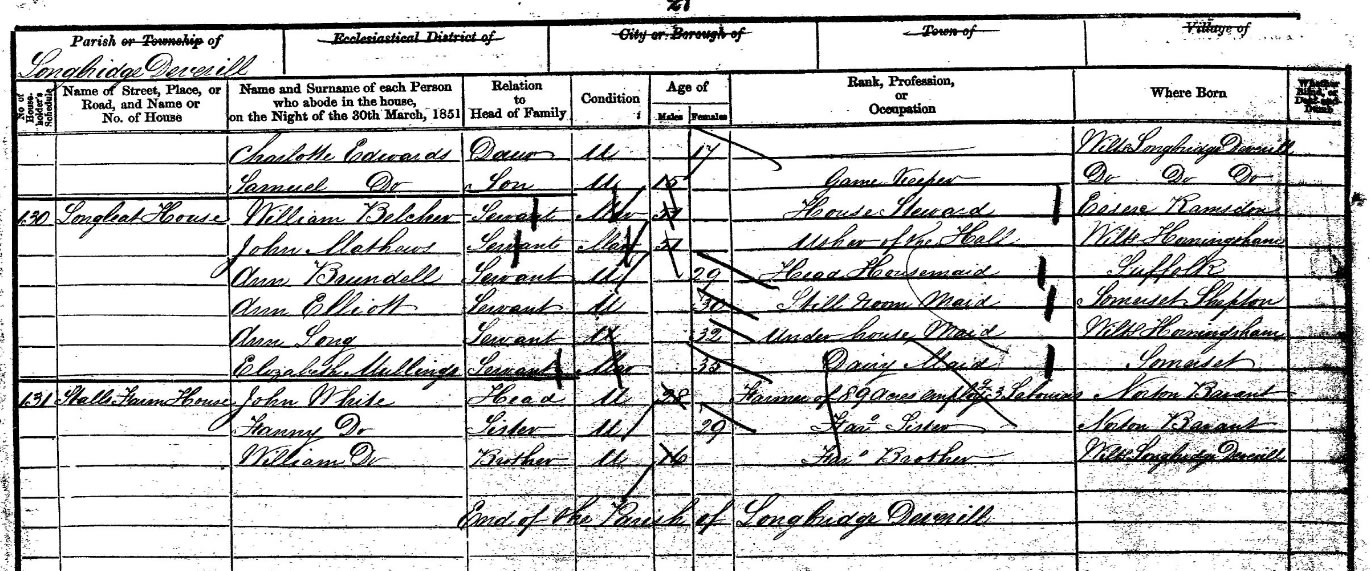

The number of servants a person had was dependant on the income of the head of the household. A large estate could afford to employ more servants than a middle class household. The census however, didn't always reflect the full complement of servants in a big house on census night. It may have been only a skeleton staff, perhaps as the family were not in residence at the time. Accessing the 1851 census for Longleat, using TheGenealogist, we see that only six servants were in the huge house that night. Revealingly, the lord and lady of the house were not present.

On census night in 1851, only a skeleton staff were present at Longleat in Wiltshire.

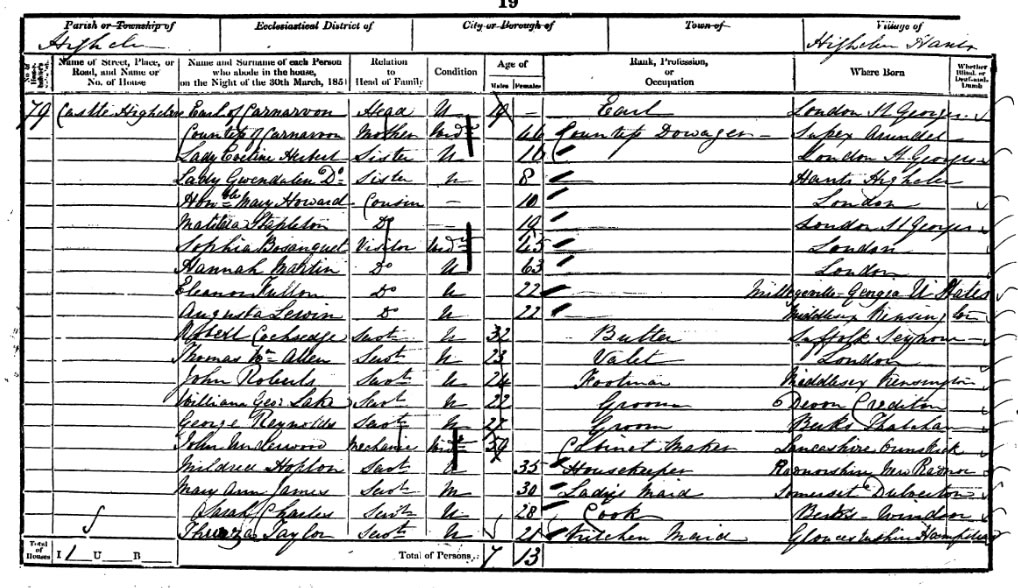

In contrast, at Highclere Castle (the house used in Downton Abbey) in 1851, the 19 year old Earl of Carnarvon and his mother, the Dowager Countess, were in residence along with the Earl's sisters, cousins, and some friends. Highclere, it appears, required 22 servants to run the house.

Highclere Castle employed many servants, as the 1851 census shows

THE SQUIRE IN HIS HALL

Country houses didn't just belong to the titled aristocracy. Some belonged to the local squire, or other members of the gentry.

In an example from Wrexham in North Wales, the Yorke family lived at Erddig Hall. The squire, Simon Yorke, and his wife, Victoria, lived with their two children in the big house. There were no fewer than nine female house servants, a butler, gardener, two male house servants, a butler, gardener, three farm labourers and a gamekeeper, with the household flowing onto another page of the census.

"In post World War 1 Britain, the lure of other work drew many away from domestic service"

What we should remember is that it was not just in the great houses and halls where servants worked. In the Victorian era, the newly wealthy middle classes would employ a number of servants may also be found in the households of the lower middle class, where money was tighter. Here, only one 'maid-of-all-work' may have been employed.

MAIDS OF ALL WORK

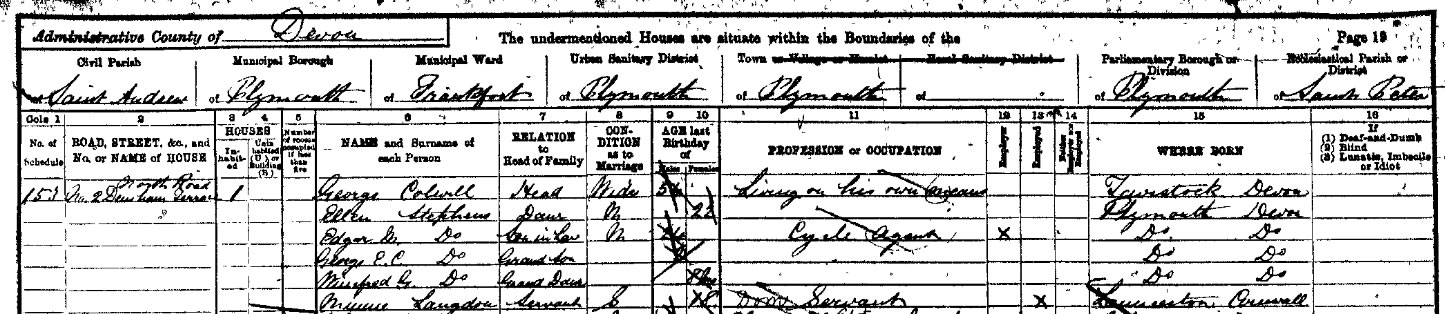

At the lower end of the middle class, my great-great-grandfather George Colwell was a retired baker and grocer in Plymouth. He was a widower and living on his own means. His small terraced house, next door to a public house, had a single maid-of-all-work to look after him and his small household. Living under his roof were his daughter and son-in-law, my great-grandparents, plus their two children (aged eight and eight months) and Minnie Langdon - an 18-year-old domestic servant from Cornwall.

The Colwells, and their servant Minnie, ase detailed on the 1891 census

By simply taking a look at the census records of very different households, we can se which social strata the head came under. From the aristocracy and the gentry, through the upper middle class to the lower middle class, the number of servants had reflected the size of their homes, and therefore their respective incomes.

"In the Victorian era, the middle classes would employ servants as a sign of respectability"

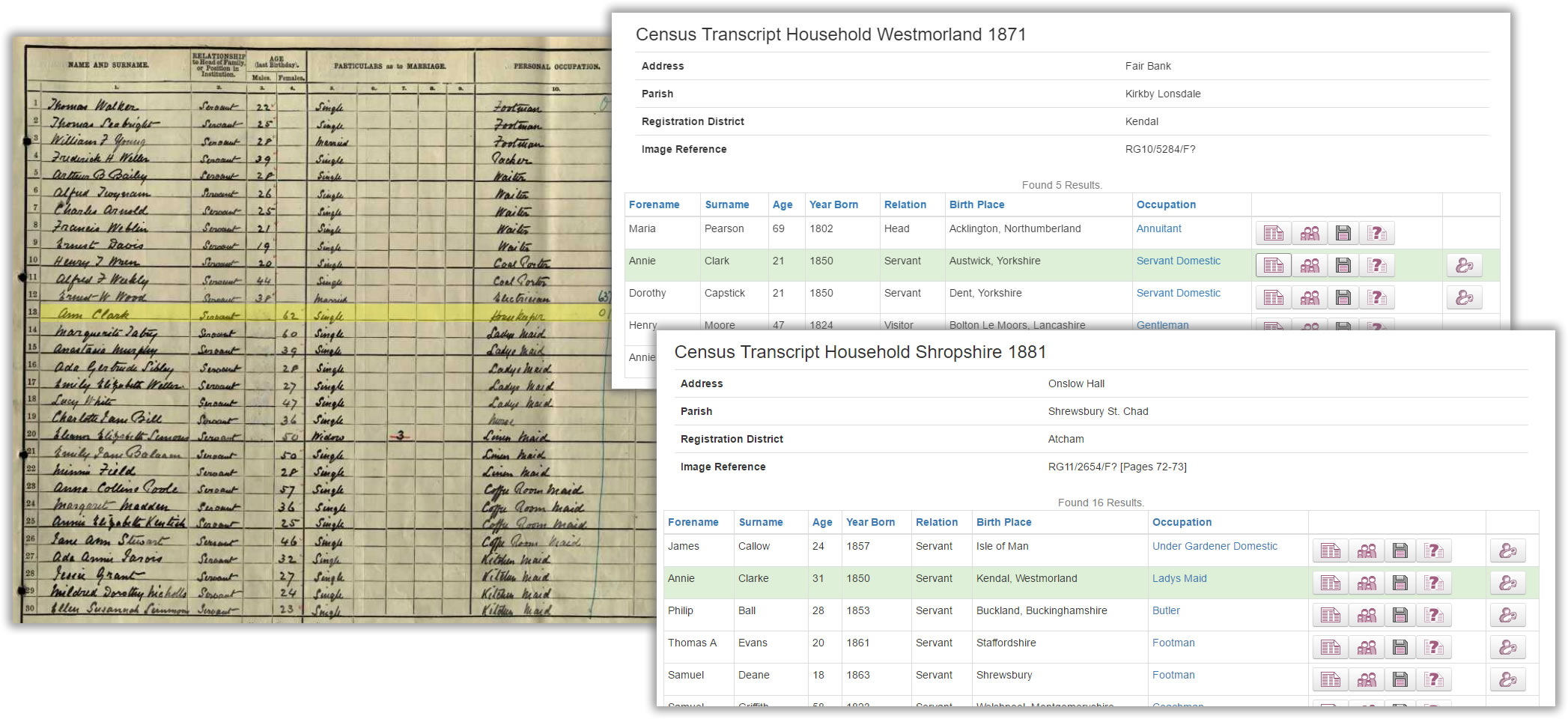

By using the records on TheGenealogist, I have been able to trace the working life of one such domestic servant who began her career in her home county of Westmorland. What is different about Annie Clark is that she ended up, at the very peak of her life in service, within the best of households in London.

ANNIE'S LIFE

Annie Clark was born in 1848 in Kirkby Lonsdale, within the Kendal district of Westmorland., as can be seen within TheGenealogist's birth records.

At the age of 21, Annie was one of just two servants to Maria Pearson at Fair Bank in Kirkby Lonsdale. We can assume from this that her duties to her mistress would have been many.

By 1881, she had become a lady's maid at Onslow Hall, Shrewsbury, and was now one of a much larger household. As her occupation suggests, her job was now more defined.

Fast-forward to 1901, and Annie Clark has moved to London, where she is now in Royal employment. She is the housekeeper at York House, a wing of St James's Palace.

But this is not the furthest that Annie goes in service - as the 1911 census, accessed on TheGenealogist, shows. Here, Annie Clark is still a housekeeper, but she is now based at Buckingham Palace, where the head of the household is listed as HM King George.

Annie in the 1871, 1881, and 1911 Census.

As can be seen from our research using TheGenealogist, this domestic servant made quite a journey, all the way from Westmorland to Buckingham Palace.