Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.London

London has always been a city of renewal – plagues and fires have decimated its population and scarred its buildings, but every time it has recovered and rebuilt itself bigger and better than before. Little wonder, then, that so many of our ancestors were drawn there, whether from dwindling rural settlements around the country or from countries across the globe.

Of course, for many of them the dream of new opportunities turned into a nightmare of slum life in the insanitary and crime-ridden ‘rookeries’. But the ever-changing city also brought with it employment in trades from cab driving to lamplighting, from being a Thames lighterman (working on barges) to a bookbinder in Clerkenwell.

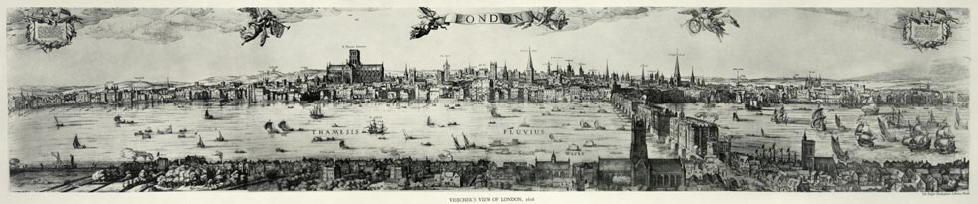

London’s expansion beyond the boundaries of the City really began in the 17th century. Immediately to the north was Moorfields, which had recently been drained and laid out in walks, but it was frequented by beggars – travellers, who crossed it in order to get into London, tried not to linger. Mile End, then a common on the Great Eastern Road, was known as a rendezvous for troops. The general meeting-place of Londoners in the daytime was the nave of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. Merchants conducted business in the aisles, and used the font as a counter upon which to make their payments; lawyers received clients at their particular pillars; and the unemployed looked for work.

St Paul’s Churchyard was the centre of the book trade and Fleet Street was a centre of public entertainment. During Charles I’s unpopular reign, aristocrats began to inhabit the West End in large numbers. Country landowners and their families lived in London for part of the year simply for the social life – the ‘London season’.

Overcrowding saw plagues throughout the centuries. As James I was about to take the throne in 1603, a plague killed around 30,000 people, and the Great Plague of 1665 killed more than twice that – a fifth of the population. Diarist Samuel Pepys, most famous for describing the Great Fire in the following year, wrote that 6000 people died in one week and there was “little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells”.

Although the fire saw little loss of life, it ultimately changed London from a medieval city to a modern one. Many aristocratic residents never returned to the City itself, preferring to take new houses in the West End, where fashionable new districts such as St James’s were built close to the main royal residence of Whitehall.

London and Middlesex Records

Leading data website TheGenealogist.co.uk has a wealth of records for London and Middlesex. Here is a quick run-down of what you can find (in addition to national collections):

- Trade directories: around 70 directories for London and a further 3 for Middlesex.

- Census records: London and Middlesex records for every census from 1841 to 1911.

- Parish registers for more than 40 London parishes and more than 30 in Middlesex (see www.thegenealogist.co.uk/coverage/parish-records/).

- Nonconformist registers: Nonconformist chapels and meeting houses across London are covered in the site’s collections.

- Land owners: the site’s huge collection of tithe commutation records includes Middlesex, along with tithe maps; plus an 1873 survey of Welsh and English landowners includes the region.

- Large areas of London are covered by the growing collection of Lloyd George Domesday Survey records from 1910: see https://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/lloyd-george-domesday/

- School/college registers for Blackheath High School, City and Guilds College, London School of Economics and Political Science, Royal Holloway College, Mill Hill School, St Pauls School, University College School, Harrow School and Merchant Taylor’s School; plus a register of admissions for Grays Inn.

- Records of the Middlesex yeomanry.

- Westminster poll books from 1774, 1818 and 1841.

- London wills from 1258 to 1688.

- Medieval visitations from 1568 and 1633.