We usually search census records to look for useful information such as where a person was on census night, as well as the names of the other members of their household. Using TheGenealogist for our research between 1871 to 1911 comes with an added benefit in that we can see the location of the property linked up to useful georeferenced maps in the Map Explorer tool. Also, TheGenealogist has now significantly improved the image quality and therefore readability of all its 1851,1861,1871 and 1891 census record images by ‘deep zooming’ the images to have five times the resolution of previous images and providing the highest resolution and quality of English and Welsh census images to be seen anywhere online.

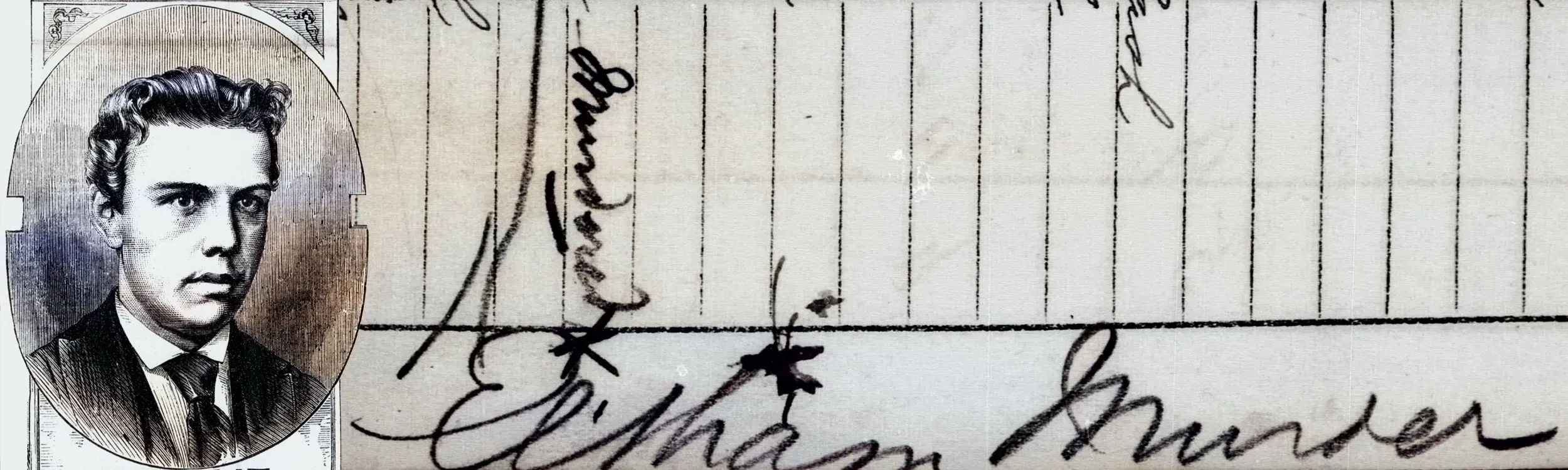

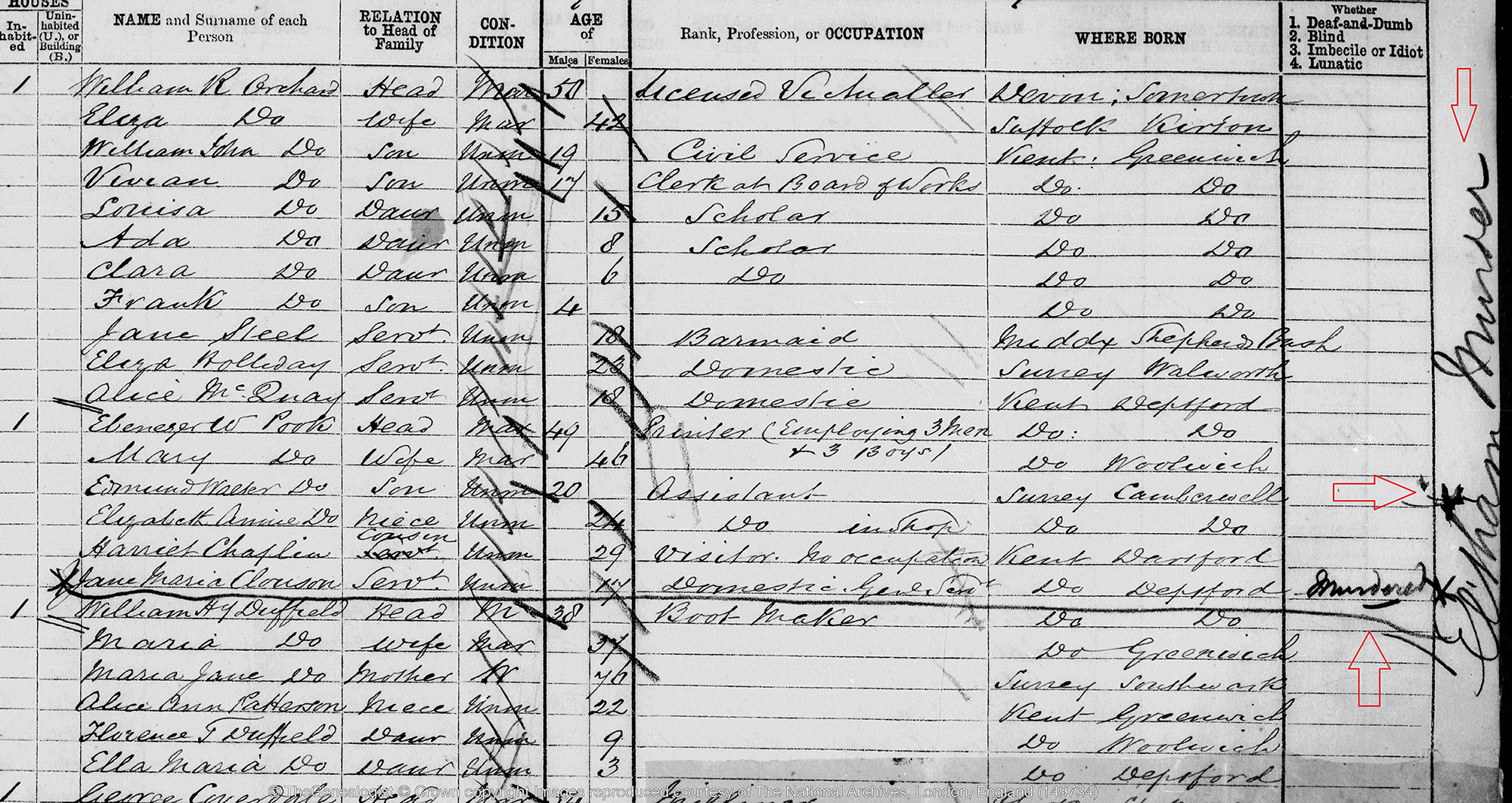

A census return can also give us other details that we may be looking for. For example the ages and place of birth for ancestors and, in the case of an infirmity, whether they were deaf and dumb, blind or suffering from mental illness. Rarely, however, has the enumerator used this column in the way that we find in a particular example from Greenwich in 1871. In this very unusual instance of a census form we see that a 17-year-old domestic servant has been recorded in the right-hand column as ‘Murdered’! Then, written vertically in the margin are the words ‘Eltham Murder’. Lastly, two asterisks have been placed against two of the names – those of the domestic servant, as well as the son of the household. The murder took place in the early morning of 26 April 1871, just weeks after the census on the 2nd of the month.

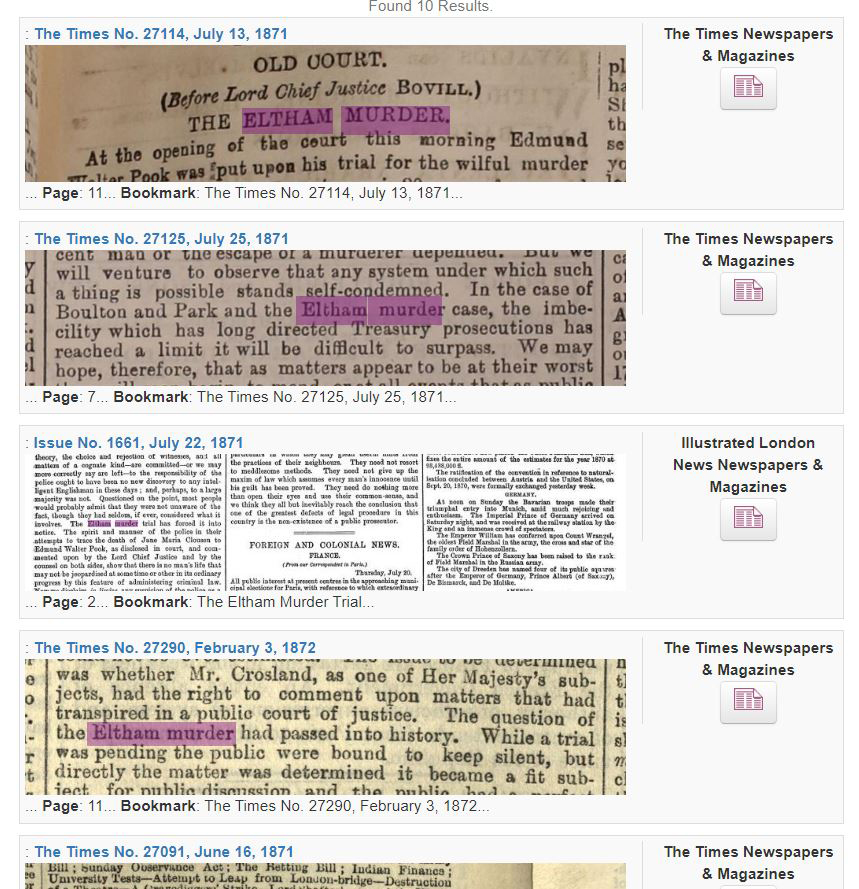

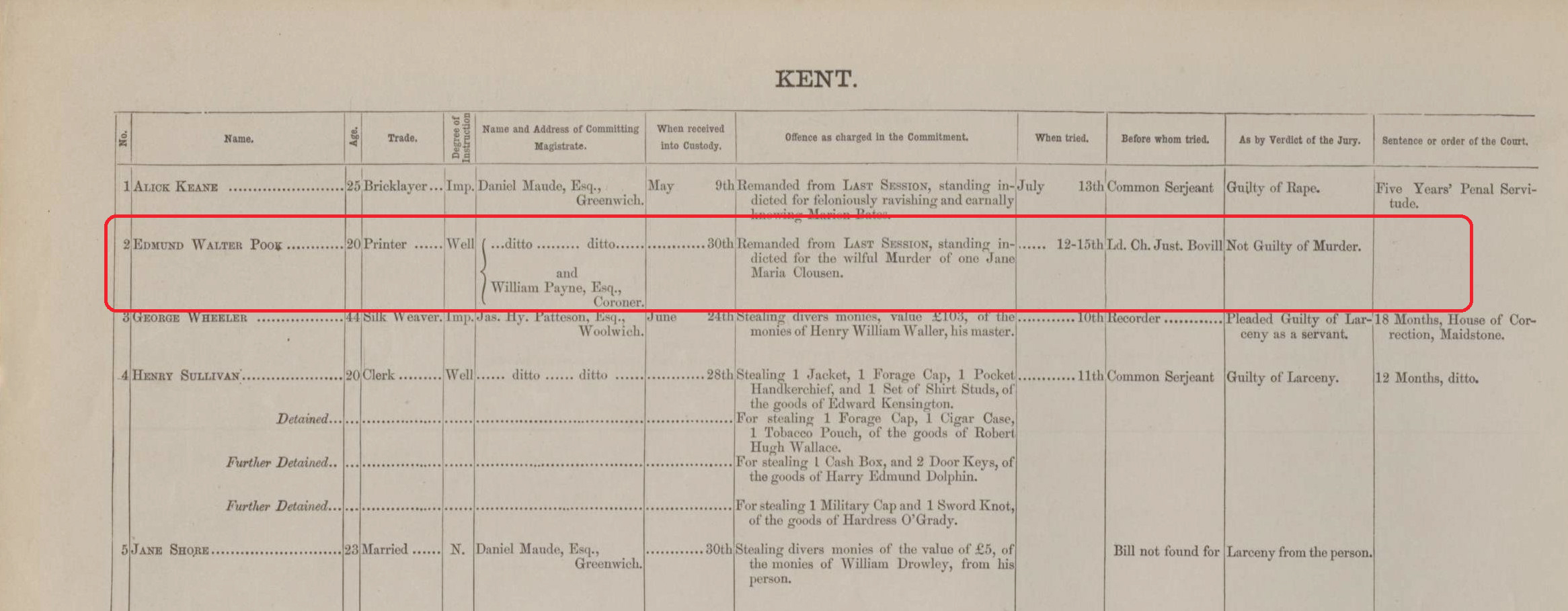

These intriguing annotations are really valuable hints – by searching using the keywords ‘Eltham Murder’ in TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazine Collection we are then able to find the terrible crime as it was reported at the time. The results tell us that the man accused of the murder was Edmund Walter Pook while the victim was Jane Maria Clousen (sic), the dismissed servant of the Pook family. Jane’s surname was continuingly written with an ‘e’ as Clousen in the reports from The Times and the Illustrated London News, as well as the official criminal records; however it was recorded as Clouson in the 1871 and the 1861 census. The civil BMD registration for her birth, found on TheGenealogist, shows the name spelt with an ‘o’ and so all this evidence points to this being the correct spelling. In the 1861 census we see that her father, James Clouson, had been a dock labourer and her mother a dressmaker at the time that Jane was a six-year-old child in her parents’ house in Deptford.

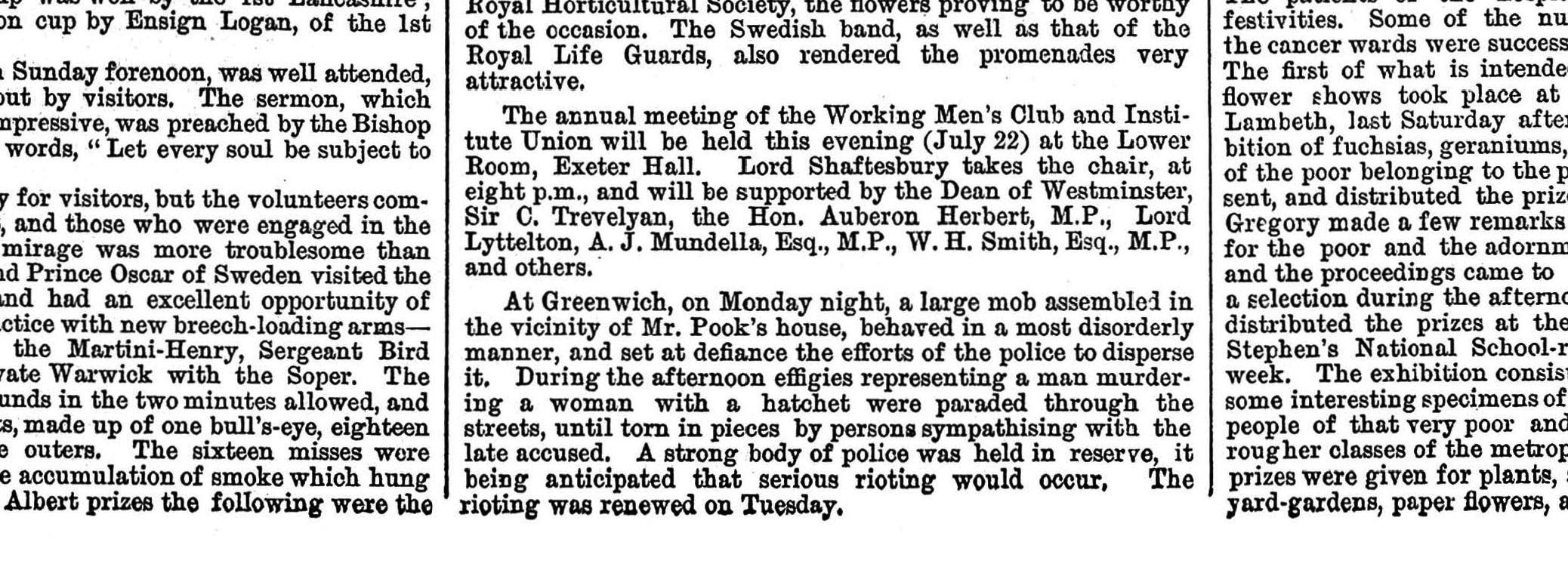

The newspapers closely followed the murder trial when it began on 12 July 1871 at the Central Criminal Court, with many of the papers, but not all, having intimated Edmund’s guilt before the trial. Fascinatingly, there were other reports that covered some of the ancillary events surrounding the trial and which are also in TheGenealogist’s records. We are able to get a more detailed picture of what went on in that summer by reading these and one thing that is noticeable is the varied lower court locations where subsidiary proceedings took place. While the defendant and the lawyer were both named Pook, they were not actually related, and in The Times newspaper of 21 July 1871 it transpires that Henry Pook the solicitor took two senior police officers to court at the Guildhall in the City of London for wilful and corrupt perjury! It being late in the day, however, the City’s magistrates had already left for the day.

With perhaps some growing amazement, we then discover in The Times, newspaper from a few days earlier that this very same lawyer was himself before a Greenwich court. Henry Pook appeared in front of the bench on a charge that on 6 and 8 May 1871 he had been guilty of ‘certain violent and indecent behaviour’ at a police station at Blackheath. It appears, however, to be different policemen from the ones that he was accusing of perjury. The officers, whom he had allegedly mistreated, had then been counter-sued by Henry Pook for abusing and insulting words and behaviour that he claimed they used towards him!

As if this wasn’t enough, the papers also report on an action taken by Mr Pook the solicitor at Bow Street Magistrates Court against a publisher. In this action he was trying to prevent the sale of a pamphlet entitled The Eltham Tragedy Reviewed relating to one of two criminal libel suits in which he represented his client.

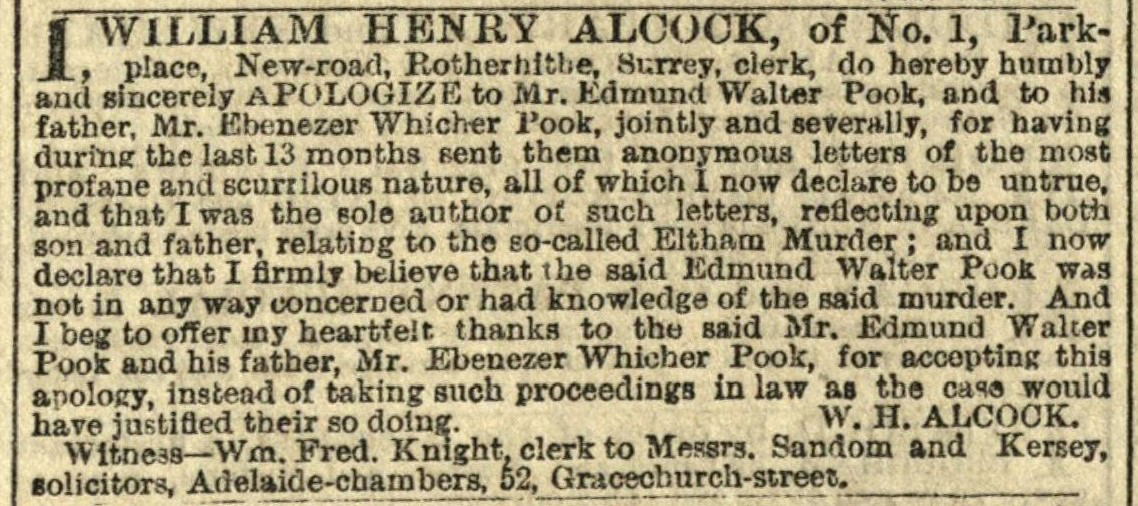

Anonymous letters

TheGenealogist’s newspaper collection reveals the

polarisation of opinion regarding Edmund Pook’s guilt with some taking it too far. In July

1872 The Times carried an apology from a solicitor’s clerk to Edmund and his father for

having, over 13 months, ‘sent them anonymous letters of the most profane and scurrilous nature’.

William Henry Alcock, the clerk from Surrey, had accepted that the content of his letters were

untrue and that he had come to firmly accept that Edmund Pook was not guilty of the murder. From the

other camp, we can see an advert placed in The Times in August 1871 asking for contributions towards

the defence fund appeal to pay the expenses Edmund Pook’s case had run up and which were then

in danger of ruining the family.

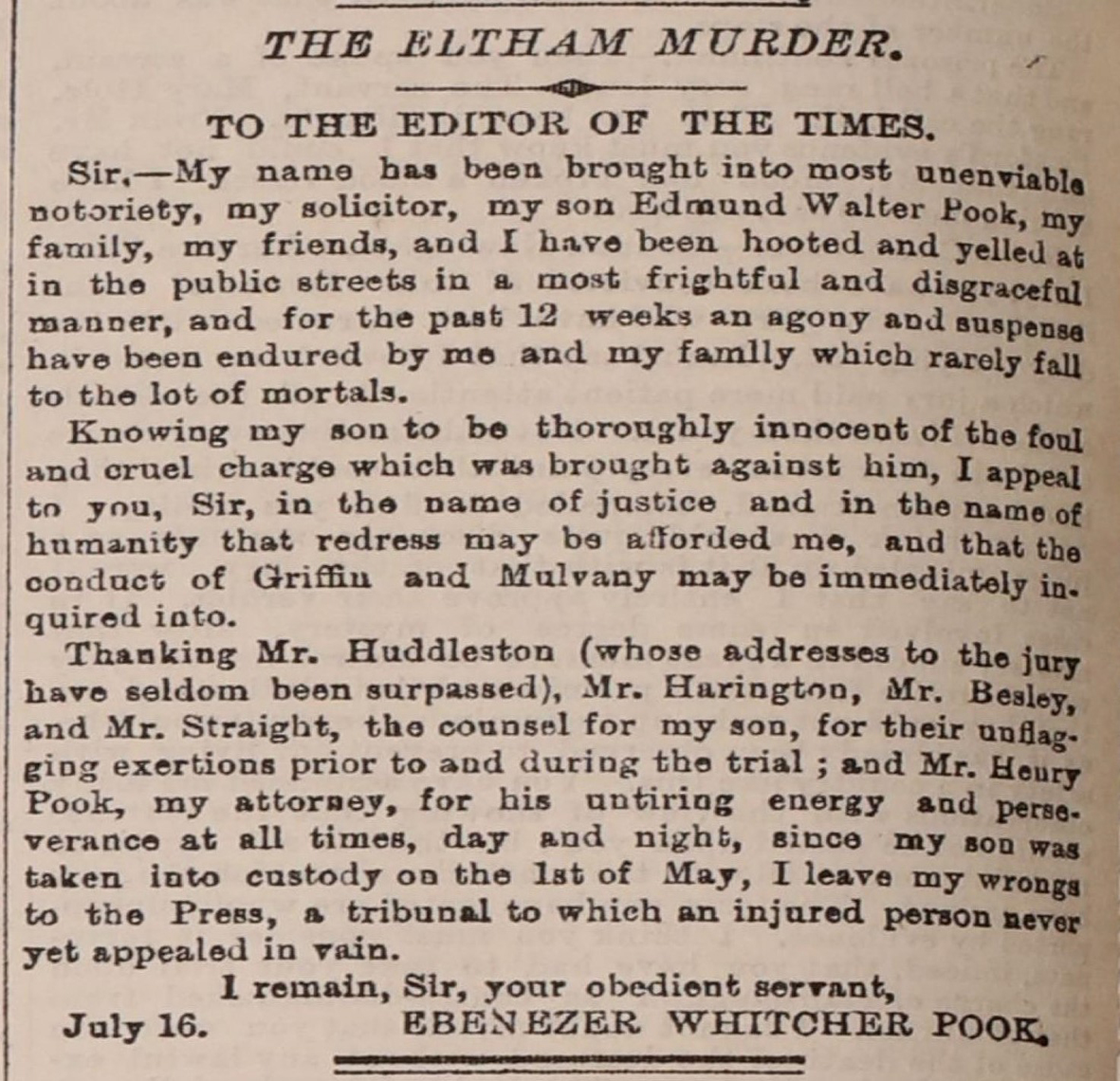

We can also find a letter to the editor of The Times from Ebenezer Pook, the father of Edmund, appealing for the conduct of the two senior policemen in his son’s trial to be investigated by the press.

Wilful murder?

Taking a step back to when the legal proceedings started in May

1871, the murder having been that April, we can read reports in the newspapers on TheGenealogist

that tell us how the jury at the coroner’s court found Edmund Walther Pook guilty of ‘wilful

murder’. There then appear various reports on Pook’s early appearances before the

Greenwich Police Court and it is in this court that a young lady witness explained that ‘she

was accustomed to meeting Edmund Pook when he would normally give a signal to her by blowing a metal

whistle’ – the relevance being that a whistle had been found near to the scene.

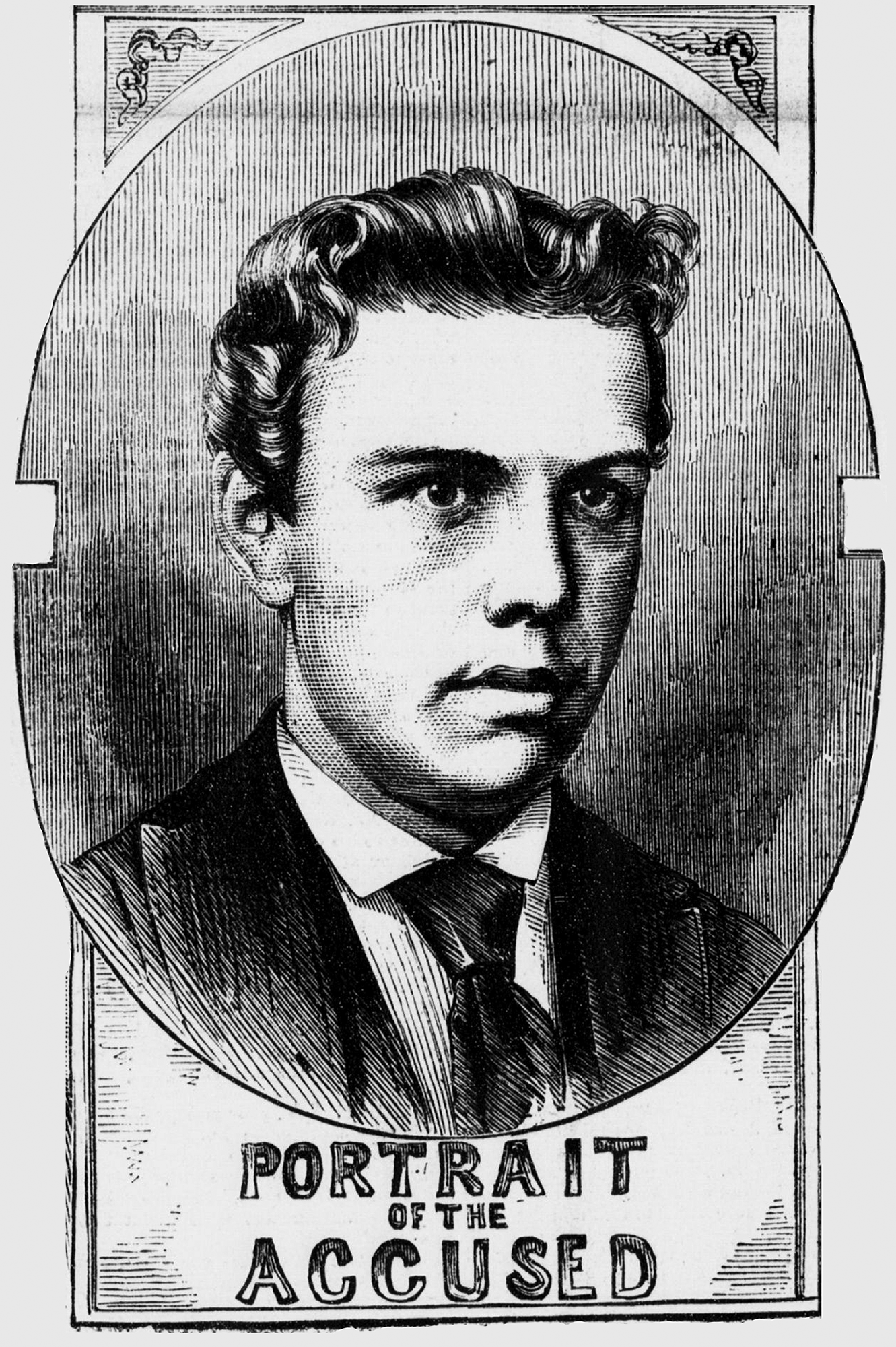

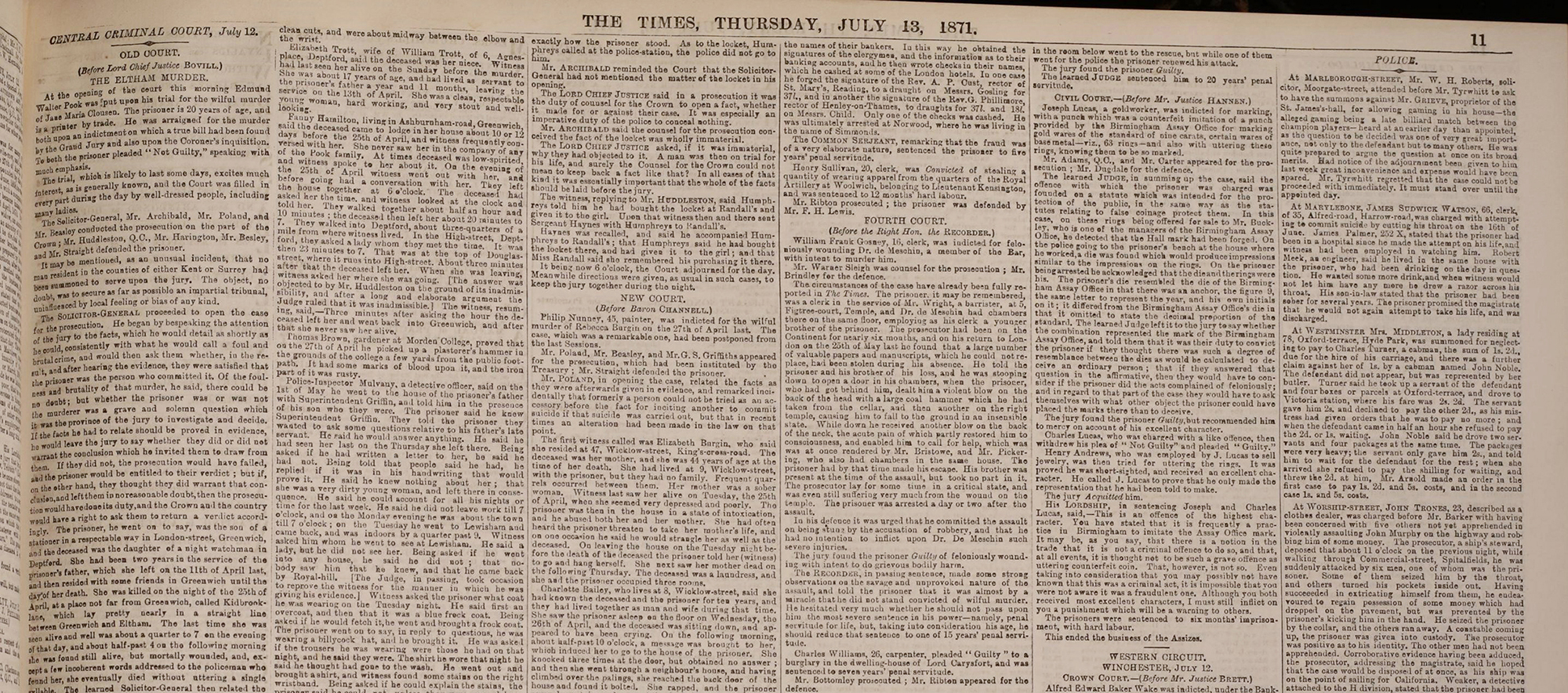

The criminal trial, before Lord Chief Justice Bovill at the Old Bailey, began on 12 July and The Times tells us that the solicitor general opened for the prosecution. He told the jury that the 20-year-old prisoner (as the defendant was called in those times) was the son of a stationer from London Street, Greenwich. The victim had been the daughter of a night watchman from Deptford. We learn that for the preceding two years, Jane had been a servant in the stationer’s household, only leaving to then reside with friends from Greenwich on 11 April. It emerges that she had been sacked by the Pooks and there was disagreement between the prosecution and the defence as to why. One scenario was that she and Edmund Pook had been seeing each other and that she had become pregnant by him. The alternative story was that she had been let go following several warnings about her unkempt appearance and slovenly work habits.

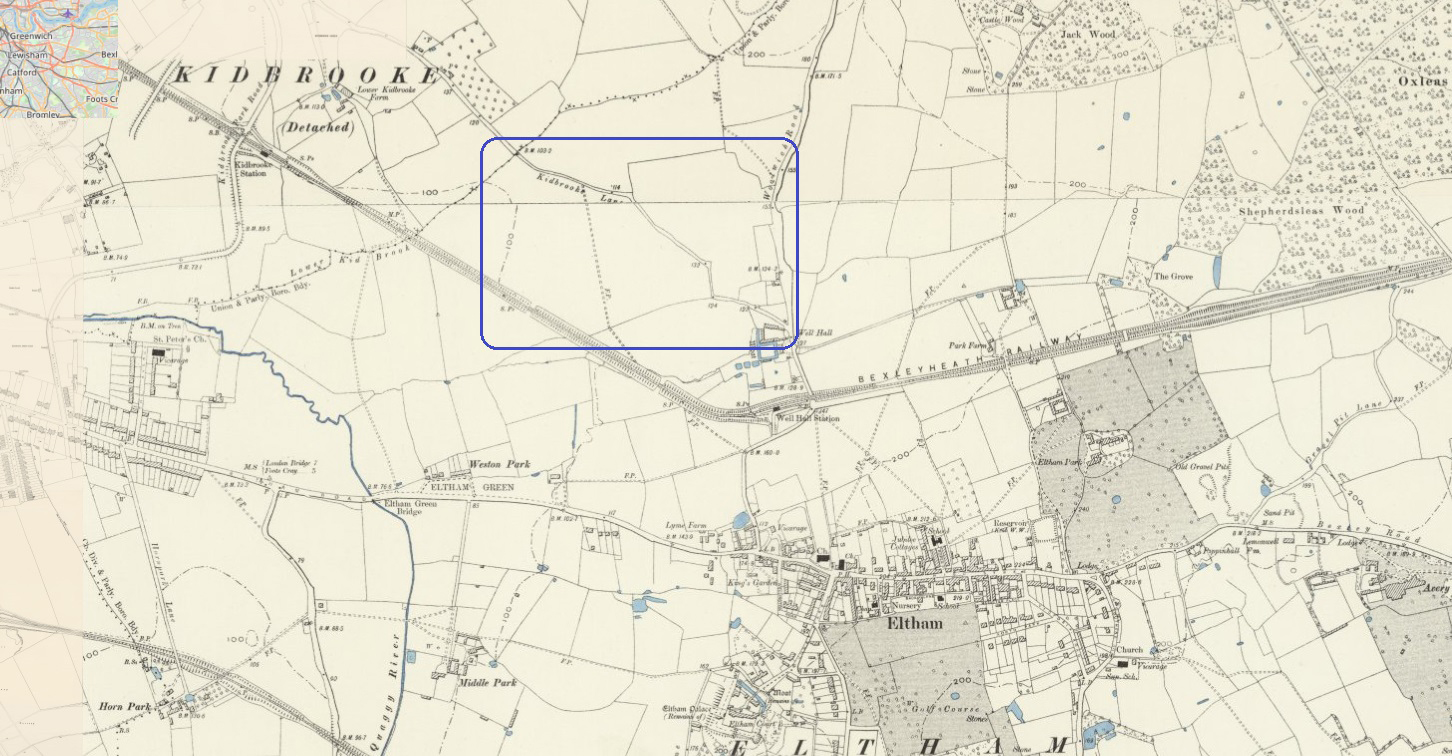

Whatever the reason for her losing her job the facts were that Jane was found, mortally wounded, in Kidbrooke Lane that ran between Greenwich and Eltham. This was at 4:30 am on 26 April 1871 and she had terrible injuries to her face and was making no sense to the policeman that had found her. A bloodstained hammer was found in the vicinity and it didn’t appear to have been a theft as her purse, containing 11s. 4d., was untouched, plus there was no evidence of sexual assault.

The policeman went for help and then Jane was taken to a local doctor. Her wounds were very serious so she was then transferred to Guy’s Hospital the next day. The most significant wounds that she had suffered were to her head, the bones of the skull being smashed and her brain lacerated. In the evening of 30 April, more than four days after being attacked, Jane died at Guy’s. Mr Harris, the doctor from the hospital, was called as a witness and, having been shown a hammer in the court, was able to confirm that it could have caused the injuries. Evidence was also presented that the post-mortem had found Jane to have been about two months pregnant when she died.

The next day, 14 July 1871, The Times continued its detailed coverage. Referring to the opening speech by the solicitor general, the paper recapped that the deceased had set out with the intention of meeting ‘the prisoner’ and that Edmund Walter Pook had been seen returning to Greenwich hot and excited and with a sufficient lapse of time that could have allowed him to have committed the murder. Other facts were that a man of similar description to Pook had been seen hurrying along a lane around the right time; Edmund Pook had blood on his clothes; and he had been enquiring at the local shops to buy a hammer, supposedly for a performance of some sort.

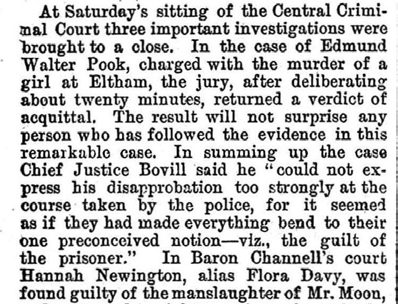

The trial took its course until, on 15 July 1871, the jury were sent out to deliberate on the evidence that had been presented. After just 20 minutes they were back to deliver their verdict – Edmund Walter Pook was acquitted of murder!

During the final day of his trial, a large throng had gathered outside the Central Criminal Court, with the courtroom itself being packed in anticipation – and this was not the result that they had expected. As Edmund Pook was acquitted by the jury and the crowd waiting in the street heard the news, their mood changed to anger and disappointment. Some thought that he had escaped justice because of his social class and family connections. With the end of the Old Bailey proceedings, the ILN for 22 July, reported that a mob had gathered at the Pook family’s house. Newspaper reports tell us that the police had difficulty dispersing the throng of angry people and fearing for more rioting they had held a strong body of men in reserve.

The crowd may have been dismayed but the proceedings, in the view of the judge, had been marred by the conduct of the police. A report in the ILN for 22 July reveals that Lord Chief Justice Bovill ‘could not express his disapprobation too strongly at the course taken by the police, for it seemed as if they had made everything bend to their own preconceived notion – viz., the guilt of the prisoner’. The Times had also run an editorial a few days earlier on the 18 July where they had raised the conduct of the police in the case, and a question was even asked in Parliament.

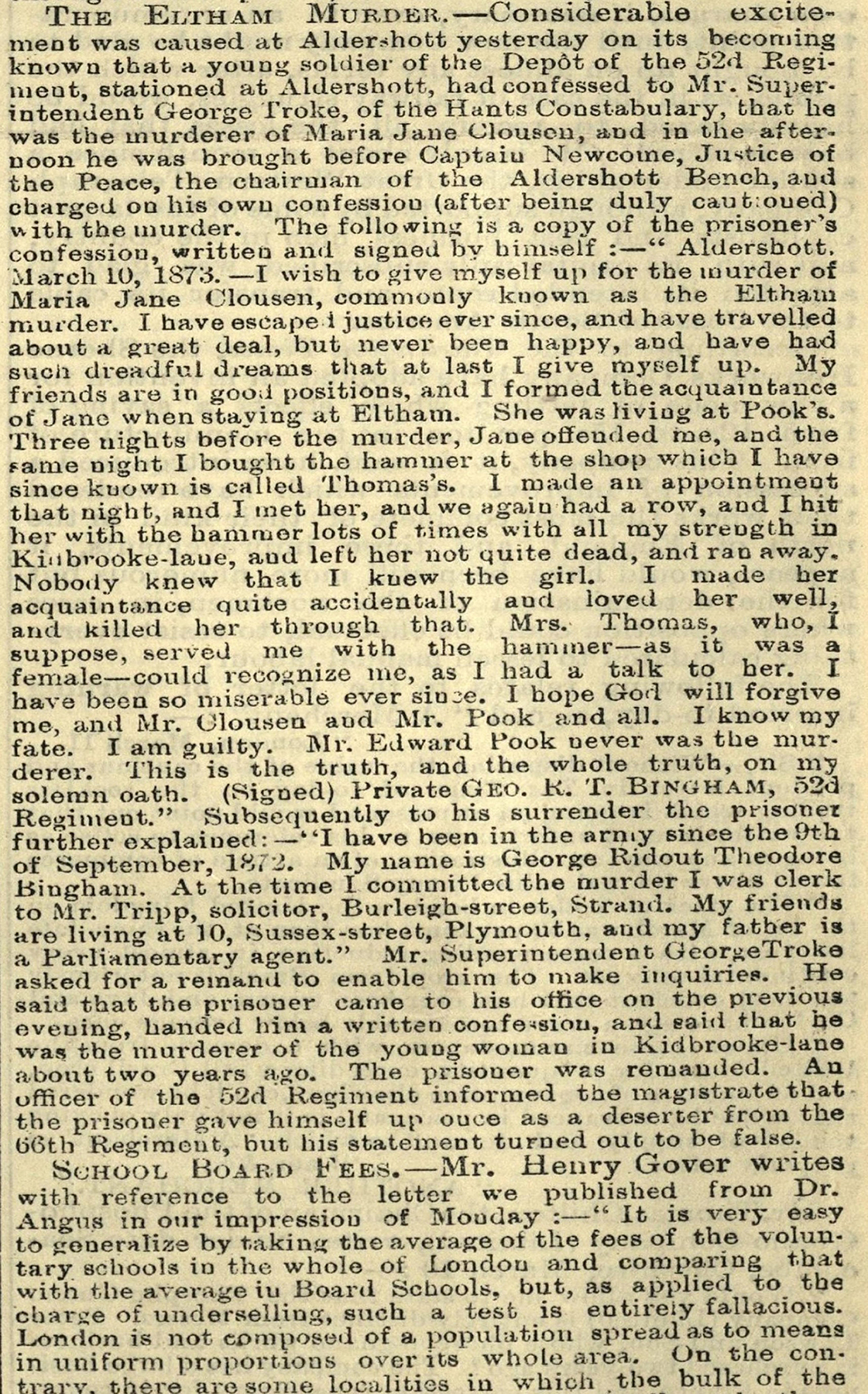

The murder remained unsolved even though, three years later, a soldier came forward claiming to have committed the murder, as we can read in a report from 12 March 1873 in The Times on TheGenealogist. By the 28th of the month, however, Private George Ridout Theodore Bingham was found to be lying. The charge of murder was dismissed, though he did receive a severe reprimand and was then remanded in custody on a much lesser charge of stealing a cash box. It turned out that he had thought confessing to Jane Clouson’s murder would be a good way to get out of the army!

TheGenealogist, with its Newspapers, Criminal records and Map Explorer tool, has allowed us to research the murder that we were first drawn to by an unusual annotation in the margin of a census page. Finding skeletons in genealogical research is just one fascinating area that searching the site’s records can reveal. {