Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Murder in the rookeries

Nick Thorne investigates a gruesome death in St Giles, London

It is interesting how neighbourhoods in which our ancestors lived may have changed from being fashionable areas only to drop down the social ladder, and then rise again. It was while I was looking at the history of the area of St Giles in London, west of Drury Lane, that I found a place with a long history of attracting the impoverished and yet also containing a once comfortably well-off person’s house.

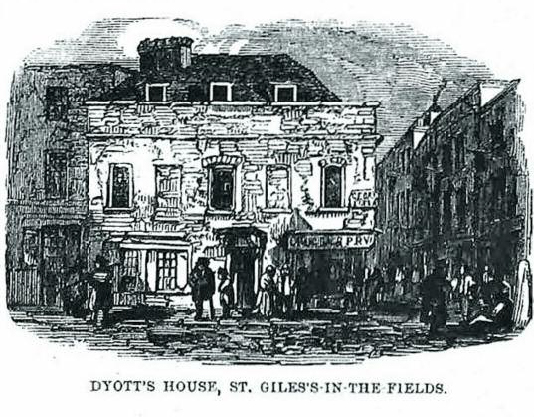

At one time St Giles was a village on the outskirts of London where a monastery had been founded with a hospital for lepers; it had then been built up in the 17th century. Some time before 1665 it became the location for the building of a large home called Dyott’s House. According to Thomas Beames, who wrote The Rookeries of London: Past, Present, and Prospective (2nd edn, 1852), the house was owned by a man of wealth called Richard Dyott. This gentleman had been an overseer in the parish and also a St Giles-in the-Fields vestryman in the 1660s. By Victorian times, however, Dyott’s House had slipped down the social scale, along with most of the surrounding area. This was not all – it then became the scene of a grim murder!

Ten years before Thomas Beames had published his study of the slums, a movement had begun to clear the rookery and build a model lodging house in the area. Until that point it had been common for the poor to be charged 3d for a bed for the night. By 1845 Dyott’s House was now one such establishment and in the ownership of a landlord called Grout. This man made a living from charging the poor to sleep in one or other of his numerous lodging-houses and, though not involved in the crime, Grout’s surname was revealed in the newspaper reports of the murder that took place in the house. While we can’t find him in the 1841 census there does appear to be a 58-year-old Thomas Grout in the next one. On census night 1851, he was recorded in another house in George Street, St Giles. Though he was not the head of that particular household, Grout’s occupation is recorded as a ‘Proprietor of Houses’. Also present is a 22-year-old unmarried woman, a glover from Woodstock in Oxfordshire. By the next census the two are man and wife, now living in Kentish Town, and have two children plus a servant in their household.

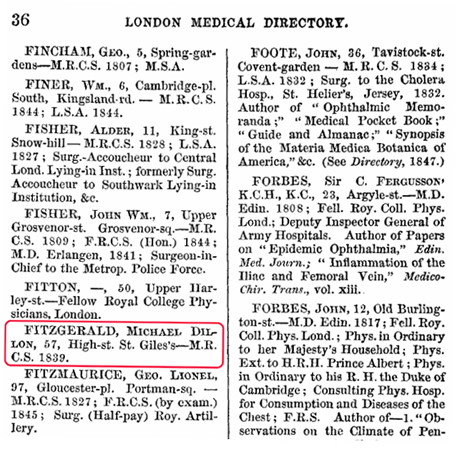

Michael Fitzgerald in 1848 London & Provincial Medical Directory

Picture of Dyott’s House Illustrated London News Oct 16 1858

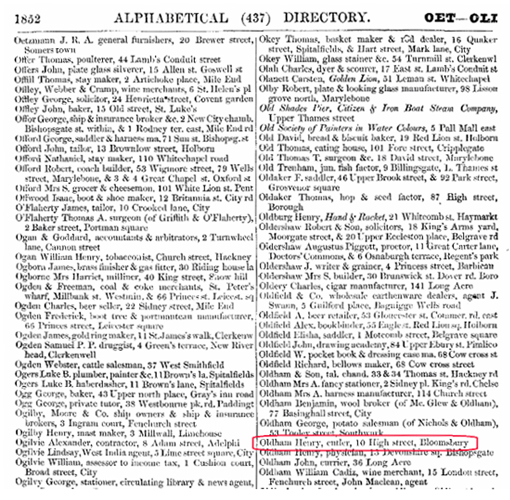

Henry Oldham, Cutler, located at 10 High Street, St Giles in the 1852 Watkins Alphabetical Directory

Murder!

The story of a frenzied murder that took place at Dyott’s House, where the perpetrator of the crime and the unfortunate victim were renting a 3d bed for the night, appears in the press at the time. The victim went by the alias of Mary Tibb or Tape, but her legal name was actually Brothers as she was still married to a man of that name. According to the evidence reported in The Illustrated London News, which can be found in the Newspapers and Magazine records on TheGenealogist, Mary Brothers and a younger man had gone to Dyott’s House at approximately 10.40pm and asked the woman left in charge for a room. In the papers the house is identified as being Number 11 George Street, St Giles. The reports state that it was owned by Grout but kept by a person called Hall as Grout’s servant. The older woman taking the money and letting the rooms was identified in the newspaper as Mary Palmer and in a later edition Palmer is described as the charwoman for the house. It was her evidence that revealed that she had heard the two parties quarrelling and she also thought that she had heard blows being rained down on the woman. Trying to prevent the assault, Palmer had then pushed in the door and saw what she thought was the man beating the woman. The assailant pushed past her to escape and it was then that Palmer could see that he had in fact been stabbing the unfortunate female with a carving knife. The weapon was still lodged in the woman’s throat.

The Illustrated London News tells us that Palmer raised the alarm which, with the station being located close by in the neighbourhood, quickly brought policeman from E Division to the scene. By looking through later street directories at TheGenealogist, it is possible to discover that the police station was actually housed at Clark’s Mews in the very street that saw the crime take place, so it was not far for the ‘Bobbies’ to come. Also summoned to the dreadful scene was a ‘respectable local surgeon’, Mr Fitzgerald. By turning to the occupational records on TheGenealogist, often useful for finding ancestors who were in the medical profession, we can see that there was only one surgeon in the area with the surname Fitzgerald. From this we can take an educated guess that he was Mr Michael Dillon Fitzgerald MD MRCS whose listing in the 1848 London & Provincial Medical Directory gives his address as 57 High Street, St Giles.

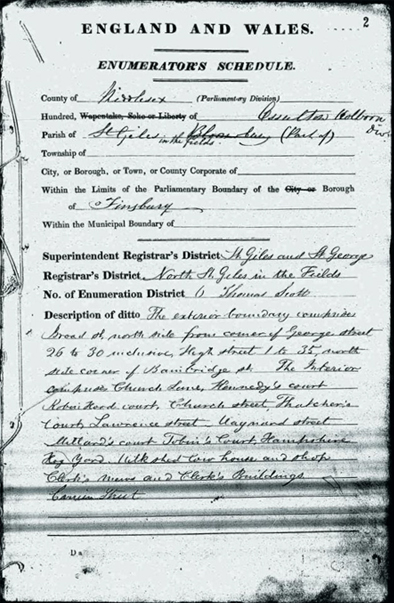

The murder reports in The Illustrated London News reveal that the weapon had been a sharp carving knife bought just before 10pm from a local cutler’s shop. The cutler, who had sold it for a shilling, was named in the paper as a Mr Oldham. Both he and his daughter were able to identify the man who had come into their shop as the prisoner before the court. Their establishment was reported to be situated just a few doors from the corner of George Street. As the street where the murder took place no longer appears on a contemporary map, we can use the description of the district written down by the 1841 census enumerator who had walked its roads. This reveals that George Street intersected with High Street, St Giles and points to it being the present-day Dyott Street. To find the cutler’s shop only requires us to consult TheGenealogist’s Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories collection. Here we are able to search for and find Mr Henry Oldham, Cutler, located at 10 High Street, St Giles in the 1852 Watkins Alphabetical Directory.

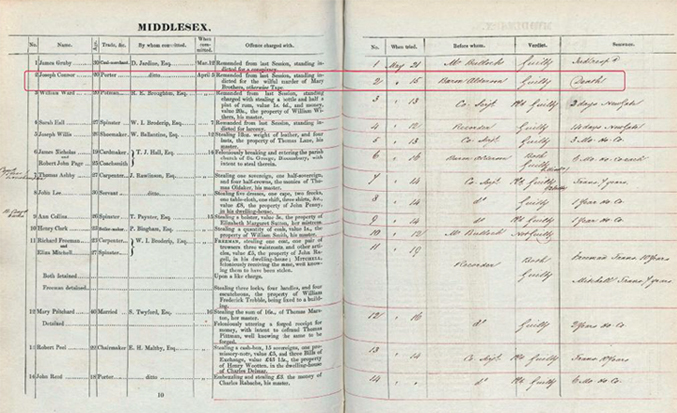

From the Illustrated London News of 17 May we are able to read that the victim suffered 16 stab wounds altogether, with one mortal injury passing through the ribs in the chest to the pulmonary artery. It emerges from the report that the defendant ‘was a good tempered, very nice young man’ who was well liked by his colleagues at Messrs Garrard’s factory where he was an honest and industrious employee of the London silversmith. In an account of the trial on 17 May, the newspaper had explained that an employee of Garrard’s had told the court that a Joseph Connor had made threats against a woman whose conduct had prevented him from marrying his cousin. Mr Ballantine, the defence barrister, argued that there was no motive for the crime and that his client had been misidentified. He submitted that many customers would have passed through the cutler’s shop and Connor had been wrongly picked out from among them. The lawyer also produced character witnesses for the accused man; they told the court that the prisoner was a quiet and inoffensive young man. Notwithstanding this defence, the prosecution had done its job: the jury retired at 6.25pm and the newspaper noted that they were back three hours and 25 minutes later with a verdict – guilty.

Description from the 1841 census, placing High Street St Giles near George Street

Newgate Prison Calendar 15 May 1845 from the Court and Criminal records on TheGenealogist

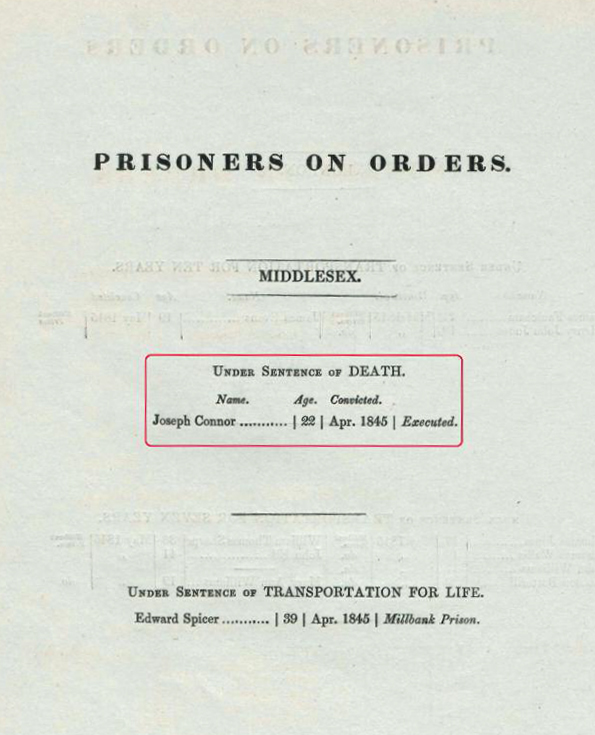

Prisoners on Orders: Under Sentence of Death

The death sentence

The two judges, Mr Baron Alderson and Mr Justice Coltman, had then put on their black caps and Baron Alderson passed the death sentence on Connor. With this information we can then turn to the criminal records on TheGenealogist, where Connor first appears when he is remanded to the next session in the records for 14 April 1845. Then on 15 May we find him under sentence of death. There then follows a record of Prisoners on Orders and this records that Joseph Connor, aged 22, convicted in April 1845, had been executed.

We can’t tell the date of his execution from this but by searching in the Illustrated London News for 31 May 31 1845 we can find that it was scheduled to be the Monday next. As the piece was published on Saturday 31 May, we can deduce that the execution was planned for Monday 2 June 1845. The article reveals that on being given this information ‘the convict heaved a deep sigh, his lips quivered, his eyes rolled in their sockets, and his whole frame became fearfully convulsed. The Sheriffs having taken their departure, the culprit shook his head, and faintly said, “Ah me! ah me!”’.

No doubt the newspaper was reporting what they believed their readers wanted to hear – that the 22-year-old murderer was racked with fear as he contemplated his forthcoming punishment.

With the mix of records available on TheGenealogist, we are able to learn about the crime and follow the trial in the newspapers through to the verdict and the days before the execution. To better understand the geography of the area we have used trade directories and occupational records to discover the address of the surgeon who attended the victim and also find the cutler who had sold the murder weapon to Connor. The Court and Criminal records then provided us with the dates of committal, trial and some other details about the convict.