Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Number One London

TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer shows London landmarks in a changing environment, writes Nick Thorne

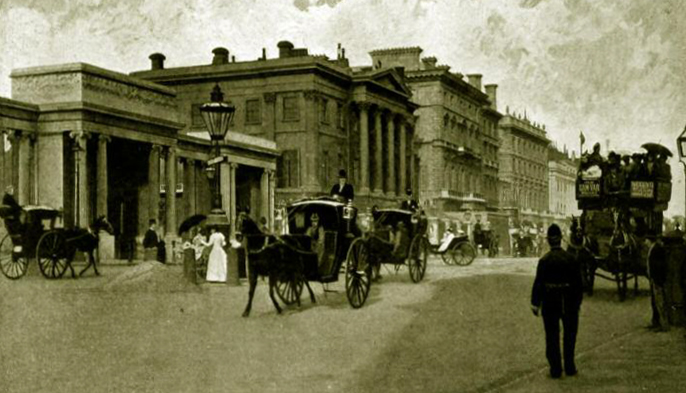

Hyde Park Corner and Apsley House, 149 Piccadilly, from TheGenealogist’s Image Archive

In the 18th century, when travellers on their way into London from the countryside had passed the toll gate at Hyde Park, they would then head up the road named Piccadilly. The first house that these people passed after they had paid their toll money then gained a nickname – Number One, London – and it has stuck to this day. It’s real address is the less catchy 149 Piccadilly, though it is better known as Apsley House and the London home of the Dukes of Wellington.

The original house had been built on the site of a tavern known as Hercules Pillars. Henry Fielding immortalised the hostelry as the place where Squire Western stayed in his book The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. The house was originally built in red brick by Robert Adam between 1771 and 1778 for Lord Apsley, the Lord Chancellor, hence the house’s name. In 1807 the house was bought by Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley and the elder brother of Sir Arthur Wellesley, who was making a career for himself in the army. By 1817, however, the Marquess was in financial difficulties and so his famous younger brother, by that time having become the Duke of Wellington, came to his sibling’s rescue. The Duke then purchased Apsley House as a London base from which he could pursue his new political career.

If you take a walk down to Hyde Park Corner today and look for the vista that is reproduced in images from the past, then you will be disappointed. While the magnificent Grade I Apsley House remains in modern times, if you don’t know the area then you may be surprised to see that the Iron Duke’s London House now sits marooned from the rest of Piccadilly by a busy six-lane extension to Park Lane. This ‘Hyde Park Improvement scheme’ was completed in between 1957 and 1962, making a change to the view forever. But this was not the first time that something like this had happened here.

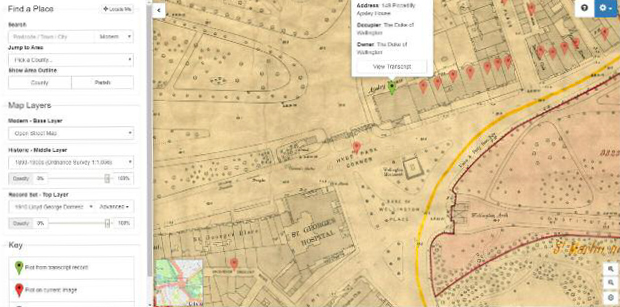

By using the Map Explorer on TheGenealogist, we can see that Number One, London is still a part of a row of houses at the time that Apsley House and its neighbours were recorded in the Lloyd George Domesday Survey of 1910-1915. By using the opacity slider, to view the modern map underneath, we can see the extent of the modern road system, implemented in the early 1960s, and how it has cut through the previous footprints of the former houses and their gardens. The Lloyd George Domesday Survey pins identify the lost properties for us.

Apsley House recorded in the Lloyd George Domesday Survey 1910-1915 before its neighbours were demolished for Park Lane road extension

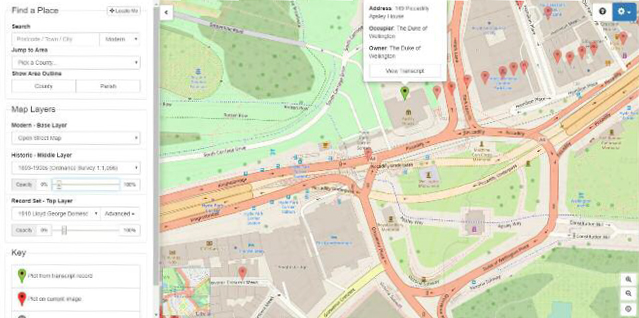

Modern road map shows houses were demolished to make way for Park Lane

Using satellite view on TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer now shows the Wellington Arch in the centre of a traffic island

Traffic once circulated in front of the famous Wellington Arch as in this picture from TheGenealogist’s image archive

Earlier road planning

But this wasn’t the first case of remodelling of the area. In front of Apsley House stands the Wellington Memorial and then a few paces southeast of this is the much larger Wellington Arch. Searching the Image Archive on TheGenealogist finds a picture of this structure at the entrance to Constitutional Hill and what is obvious immediately is the traffic circulating around the memorial and across the front of the iconic archway.

The historical maps on the Map Explorer show that the Wellington Arch once stood at the corner of Green Park as an entrance to Constitutional Hill and leading to Buckingham Palace. Fading the modern satellite map up shows how the Arch has now become more of a central feature in a huge traffic roundabout and so no longer has vehicles passing so close by as in the old photographs.

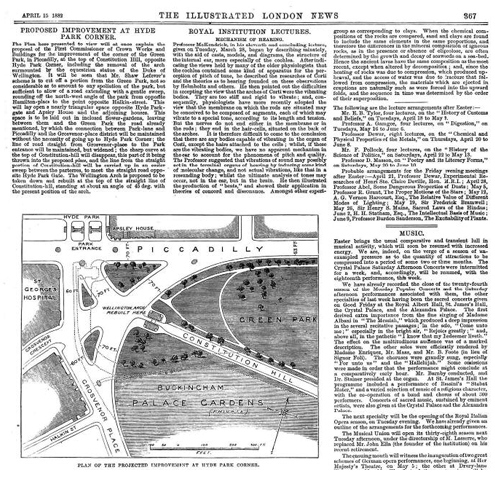

But this is not the only change that has happened to this well-known monument since it was first constructed in 1826-1832. By using the Newspaper and Magazine collection on TheGenealogist we can read the proposals to move the entire arch to its present location in April 1882. The Illustrated London News published a plan that showed the proposed movement of the archway from its original position, opposite the Hyde Park Screen at the entrance to Hyde Park, and in line with St George’s Hospital, to be relocated at an approximate 45˚ angle from its previous alignment to where it stands today. The previous road layout was rearranged from the one that we see in the historical maps in TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer and so this shows us that the 1960s road layout was not the first attempt to ease the flow of vehicles in this busy part of the metropolis.

The Illustrated London News 15 April 1882 from TheGenealogist’s Newspapers and Magazine collection

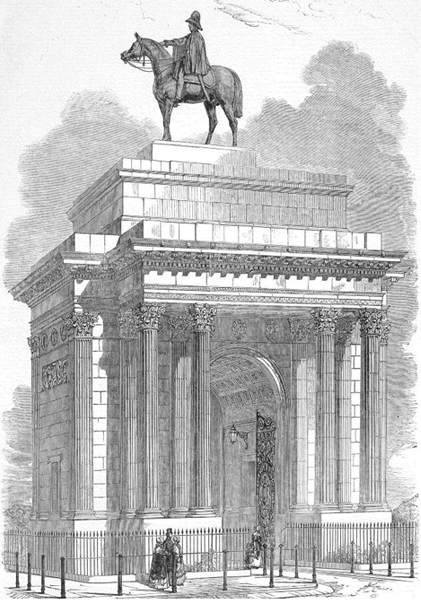

The Wellington Statue on top of the Wellington Arch

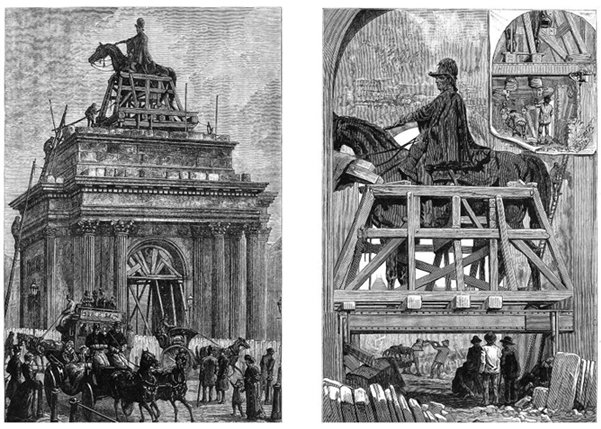

Removing the equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington in 1883

The unadorned Wellington Arch prior to the erection of the Quadriga in 1912

Change atop the plinth

Altering the triumphal arch’s situation in front of Apsley House was not the only change made. The opportunity was taken to also change the statue that sat on top. Many of us will be familiar with the statue that is there today, if only from photographs of London. It is the splendid chariot drawn by four horses and many of us will have wrongly assumed that it had always been there. This was not the case, however, as it was only in 1912 that it was put in place.

In its early days the arch had a huge equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington astride Copenhagen, his horse – though this piece, by the sculptor Matthew Coates Wyatt, was not to the liking of the arch’s designer, Decimus Burton. He, along with many others, disliked it for being out of proportion with the arch beneath. It is said that he felt so strongly about this sculpture that he left a sum of money in his will for it to be removed!

Of course the idea of taking it down could not be thought of in the Iron Duke’s lifetime. It would be 30 years after he died in 1852 and the proposed moving of the archway in 1882 presented an opportunity to remove the Duke and his horse. Today it is in a new home at Aldershot.

A search of the Newspapers and Magazines records on TheGenealogist tells us more about the removal. The 10 March 1883 edition explained how painstakingly long the process of lowering the gigantic statue to the ground would be. The engineers were using hydraulic jacks, wooden slips an inch thick which could be removed gradually and with the statue in a frame of iron girders. It was first moved to St James’s Park.

The unadorned arch then waited almost 29 years, until January 1912, to be topped off with the Quadriga by Captain Adrian Jones, a former army veterinary surgeon. The bronze sculpture depicts Nike, the winged goddess of victory, descending on the chariot of war, holding in her right hand the classical symbol of victory and honour, a laurel wreath. By searching within the Image Archive there is a picture of the unornamented arch in its new location at a time when horse-drawn transport was the norm.

While we may not have ancestors who lived in such a grand house as Apsley House, nor had monuments of the size of the Wellington Arch erected to honour them, we too may discover that our forebear’s home and the roads around it may have been subject to town planning that changed the layout of the road. In some cases the road may have been rerouted or, like the houses that once stood next to Number One, London, an ancestor’s home has been demolished completely. By using TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer and a combination of historical maps overlaid with modern ones we can find exactly where they once lived.