Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Our survey says…

From diverted waterways to lead pencil drawings of major arterial roads to come, Nick Thorne shows how newly released records from the Lloyd George Domesday Survey can aid researchers

The latest release of records from series IR 121 at The National Archives by TheGenealogist brings family historians an interesting batch of Valuation Office survey records from the period between 1910 and 1915.

Known also as the Lloyd George’s Domesday survey, this attempt to raise income from rates was one part of Lloyd George’s famous ‘People’s Budget’ of 1909. For the first time the Field Books, which can contain some interesting details of an ancestor’s property, accompany the detailed ordnance survey records on TheGenealogist. The new release is for rateable property in the Barnet area at the time of the survey and can be a godsend for the family historian looking for where their ancestor lived. The books can give detailed descriptions of the property and the maps will pinpoint the exact location of the property on a map contemporary to the period. If your ancestor’s house has been demolished, the road remodelled in some later redevelopment, or a major new route was cut through the area, then a modern map will not identify where your ancestor lived. The valuation records and maps from the 1910s could be the answer to take your research forward.

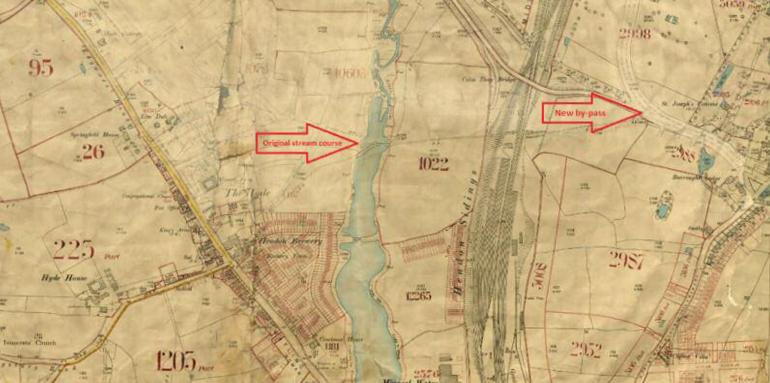

Looking at map 034, for a part of Barnet in the 1910s, we can see how much broader from bank to bank the Silk Stream had been in those days. Tracing the stream back past the Mineral Water factory, once owned by Schweppes, and the Hendon Brewery we then see that the Silk had then displayed a more naturally winding course, with many twists and turns, than the same watercourse does today. On a modern map or satellite image, it appears that reclamation and rerouting has tamed this stream to allow for new building developments since the time of Lloyd George’s Domesday survey.

Map 034 for Barnet revealing a much broader Silk Stream and the start of a major by-pass

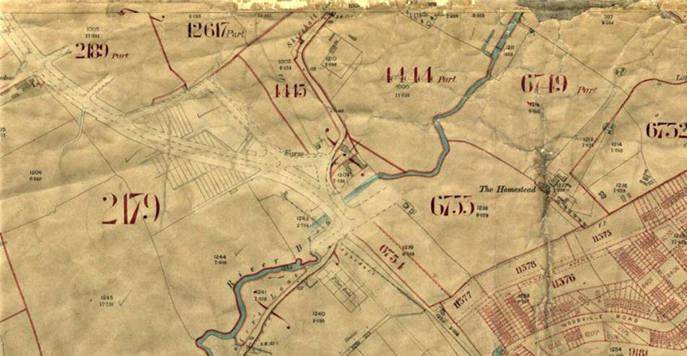

Map 038 revealing the addition of Barnet by-pass in pencil

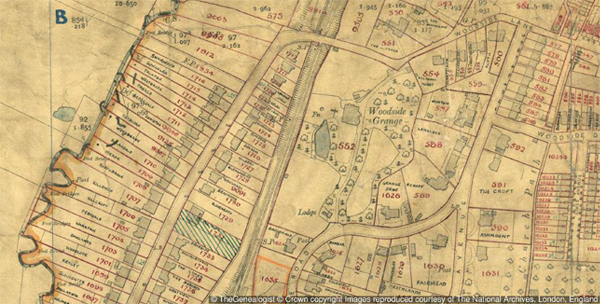

Section of map 029 with house names

‘From small pencil lines major traffic jams will emerge’

While researching in this new resource, my attention was drawn to a faint and neat graphite track sweeping through this area of London. The leader of the team preparing the records for release at TheGenealogist showed me the marks and reflected on the coming gridlock that would emerge, saying ‘from small pencil lines major traffic jams will emerge’. A glance at the top right hand corner of map 034 shows a pencil-drawn broad track of what would become the A41 Watford Way or Barnet by-pass. As it cut its way through the countryside, this arterial road would also require the demolishing of some buildings, such as part of Daws Lane in Mill Hill. Some years later on the M1 would also travel parallel to this road for a distance and level even more properties in its own wake. Turning then to examine the area to the north, map 027, we are able to follow the pencil line as it predicts the alteration of our ancestors' environment for ever.

House names for long-demolished properties

A number of the Barnet maps give researchers the names of the properties carefully annotated by the surveyors to reveal the Edwardian owners’ personalisation of their homes. One such is map 029 and if we zoom in on Holden Road we can find named houses that have long since been demolished to make way for modern developments of flats.

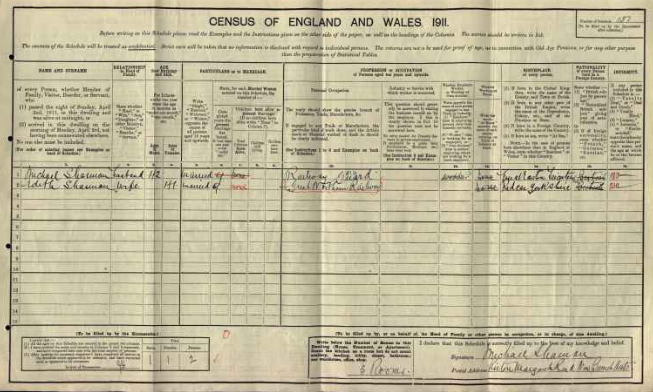

1911 census record for railway guard Michael Sharman

Map 007 displaying a particularly colourful portrayal of the area of New Barnet

Splashes of colour

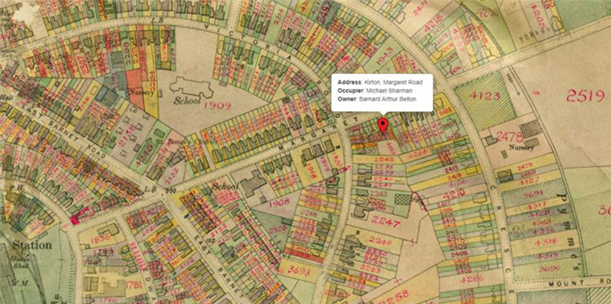

While all the maps are in colour, some of the maps used for the Valuation Survey of Barnet are more striking than others. Let us look for a typical resident in the area around New Barnet Station who appears on a map that boasts great splashes of colour.

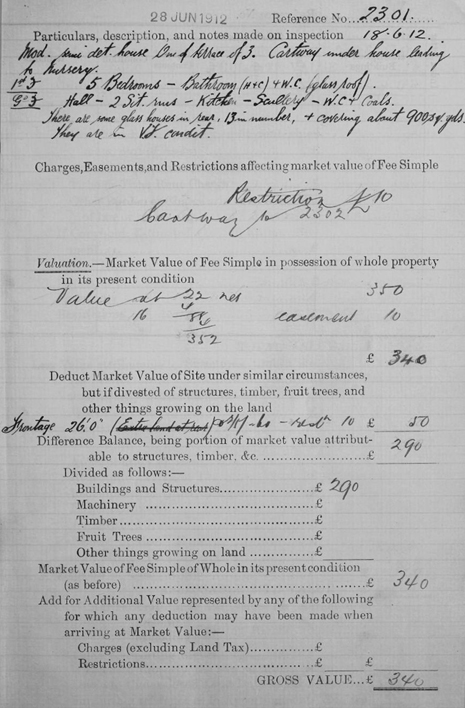

In the 1911 census a railway guard on the Great Northern Railway named Michael Sharman lived with his wife, Edith, at a property called ‘Kirton’ in Margaret Road, New Barnet. By using the 1910 Lloyd George Domesday Survey on TheGenealogist we can now find the exact plot that corresponds with his terraced house ‘Kirton’ and see that it was just a stone’s throw from the railway station at the end of the road – presumably making it easy for him to get to work. From the field book we can see if an occupier rented his house, who the owner was and the property’s rateable value. Other details can tell us about the state of the property, the number and types of rooms such as whether they had a scullery, laundry and for wealthier properties if they had billiard rooms, libraries and servants halls. Where there are out buildings these will be identified and may give a clue as to an ancestor’s livelihood, such as in the example above where a plant nursery was operated behind the house with a cart way under part of the house.

These Lloyd George Domesday records can be useful to the family historian as they can help us to not only identify the exact house on a map, but also give us a written description of the property. By browsing the maps we can get an understanding for the area in which our ancestors had lived. Roads may have changed significantly since their time. In some places streets may have disappeared completely and so don’t appear on our current maps. New routes may have been cut through the urban-scape and so what was beneath them has gone. London is a city where all sorts of change has taken place over the years whether from the German bombing in the Blitz, or property development in the years between. Small terraced housing may have made way for a block of flats, or a massive office development and so to be able to find where our forebears lived in the 1910s this major new resource will be of huge value to the family history researcher.

An example of a field book with a description of house and 13 glass houses to the rear