Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Plotting the past

With the largest online collection of tithe records complete, and colour maps coming soon, Celia Heritage explores this invaluable resource

In December 2015, data website TheGenealogist, in partnership with The National Archives, completed the first stage in its historic digitisation of tithe records for England and Wales. This is one of most important projects to be undertaken by any genealogy company in recent years and will provide a wealth of detail about your ancestors, rich and poor, and the way in which they lived. Many family historians focus on using records that relate directly to their ancestors such as birth, marriage and death certificates, parish registers and census records. While these records were created specifically to record details of the population, tithe records were created primarily to put an end to an out-of-date tax on agricultural output. You might think that this is not the best source from which to learn more about your ancestors, but that could not be further from the truth!

The tax in question, known as the tithe, was an ancient levy on agricultural output: a tenth of any profit made from crops, livestock and also products such as eggs and milk was taken by the church and, from the mid-16th century, also by secular land owners who had bought land previously owned by the church before the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Although now in the hands of laymen, the right to levy tithes went with the land, and this right could also be sold on as a separate commodity. These secular tithe owners are referred to as ‘lay impropriators’. By the 19th century tithes were a headache for all concerned: the tithe owners, the tithe payers and also the government. Tithe was an outdated from of tax in many ways and much resented by those who had to pay it.

In many places it was still paid ‘in kind’, which meant the tax was not collected as a cash payment, but by handing over a proportion of the farmer’s livestock or crops to the tithe owner each year. He then had to find somewhere to store them. Many tithe owners built large barns for this purpose and some of these survive today. Most people resented having to pay a tax to lay impropriators, while tithes paid to the Church of England were resented by those people who belonged to other(Nonconformist) churches. By the early 18th century, long years of war with France and a series of disastrous harvests meant the economy was in a sorry state and farmers were hardest hit. Meanwhile, the government was trying to encourage them to introduce new farming methods, which would result in greater agricultural output and which would help feed the growing population. Few could afford to make these improvements, however, and many of those who could refused to do so when their profits would be drained by the unfair tithe system. This growing resentment contributed to a series of riots across the country but worst in the South East. Ever fearful of social unrest, the government identified tithe payments as a major course of the problems. Between 1817 and 1836 there were a number of failed attempts to pass bills to change the tithe system through parliament but this was only finally achieved in 1836 when the Tithe Commutation Act was passed. The act changed the tithe system forever, abolishing all payments in kind and replacing them with a much fairer system of tithe rent charges based on the seven-year average value of wheat, barley and oats to avoid hitting farmers hardest when harvests were poor.

WHAT DO TITHE RECORDS REVEAL?

- They show details for anyone who owned or occupied any piece of land subject to tithe

- They will help you determine the exact position of the land or house your ancestor owned or occupied. Use the plot number to locate it on the tithe map and then compare with modern Ordnance Survey maps or use Google Earth to virtually visit the site.

- They record the name, or give a description, of each piece of land, what it was used for (arable, meadow, shop etc.) and its acreage. They also record its value for tithe rent purposes.

- You will learn more about your ancestor’s status and wealth. He may have owned many plots of land you knew nothing about, while if he had several fields turned over to pasture land, this indicates he kept livestock.

- The records will help you understand the nature of place your ancestor lived in; its layout, land distribution and also local farming practices or industries.

- There are records for approximately 75% of England and Wales. There are no tithe records where payments in kind had been changed to cash payments by local arrangement prior to 1836 or where the land was not subject to tithe for historic reasons. Scotland and Ireland are not covered because tithes were abolished in these countries before 1836.

- The maps were produced between 1837 and 1855 and alterations we made using OS maps up until 1936. These maps can be used in tandem with census returns and the 1873 Landowners’ Returns available on TheGenealogist to build a picture of the your ancestor’s town or village.

The Project

TheGenealogist's massive tithe project began in 2014 and is the only project to include all tithe maps for England and Wales. There were over 12,000 maps and their accompanying schedules to be filmed. The original records are held at The National Archives in Kew and county record offices. The first step was to scan the microfilm copies of both types of records make them available to the public as soon as possible. Apart from filming the records, transcriptions of the schedules also had to be made in order to create a searchable index. Generally speaking, each schedule contains hundreds of entries relating to the various plots of land that made up each tithe district – over the whole collection there are 14 million entries. Each entry had to be linked to a pin pointer on the tithe map to enable the plot to be easily located on the map with a simple mouse click. While tithe maps were not produced to standard specification they do have certain things in common. All are large-scale maps and the great majority use colour to help depict features in the landscape, such as houses (pink), outbuildings (grey) and watercourses (blue). They also indicate boundaries, roads and paths and of course individual plots of land while some maps depict woodland and hop gardens. The maps cover not just rural, but also urban areas, since tithes date back to the tenth century when few towns had developed. The next stage of TheGenealogist's project involves scanning the original colour tithe maps. This can only be done once each map has been assessed by TNA’s conservation team and any necessary conservation work has been carried out. The first of these will be released this year starting with Surrey, Northumberland and Westmorland. TheGenealogist is funding the conservation process and so helping to preserve these maps for posterity.

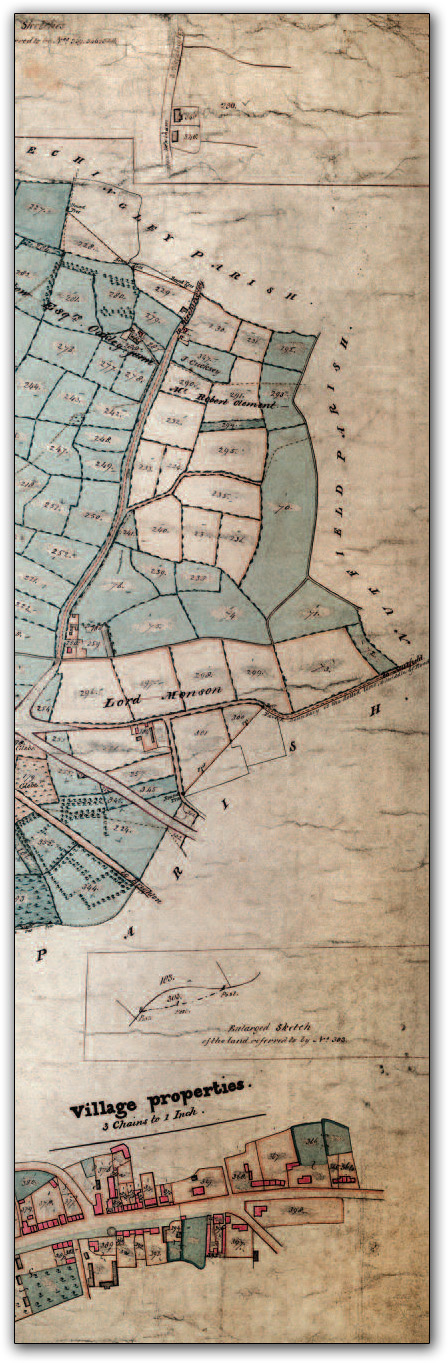

An 1838 tithe map for Merstham, Surrey, showing the amazing level of detail available. Colour maps such as this are currently being digitised and will exclusively be available online at TheGenealogist.co.uk

IN FOCUS:FIND YOUR ANCESTOR IN TITHE RECORDS

TheGenealogist.co.uk has completed its digitisation of 19th century tithe commutation records and maps for England and Wales – here Celia Heritage explains how to use them

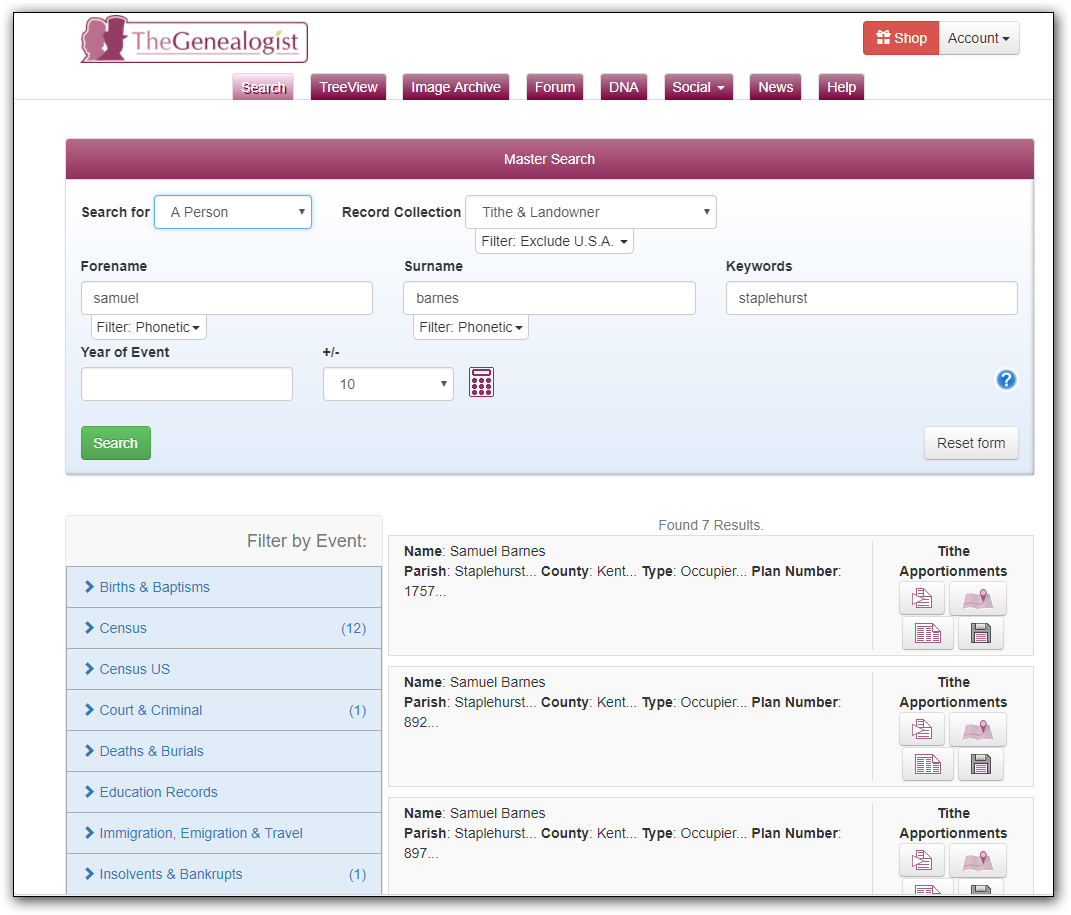

I looked for my ancestor Samuel Barnes, an agricultural labourer living in Staplehurst in Kent. From previous research using census records I knew he occupied a cottage which was part of ‘Knox Bridge Cottages’ on the outskirts of the town. Ordnance Survey maps did not name Knoxbridge Cottages and it was unclear which of the various rows of cottages in the area they referred to.

Selecting the ‘Search page‘ on TheGenealogist website you can search using a person’s name and, if you wish, also specify a county and tithe district, which is usually the same as the parish name. You can also specify a plot number only to find out who owned or occupied a particular piece of land shown on the map. I searched for Samuel Barnes in Staplehurst, Kent. The index showed that Sam occupied three plots of land. This was new information for me as census records only show details for the property where an ancestor spent census night, and his other tenancies are not recorded elsewhere.

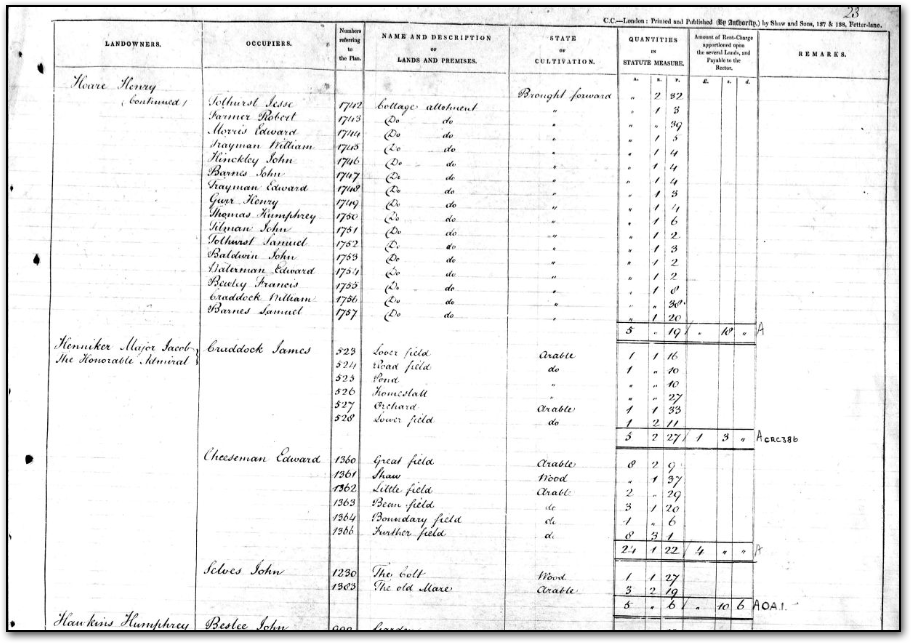

I firstly clicked through to see the original image of the schedules for each plot of land. (You can also view a transcription). Plots 892 and 897 were on the same schedule page since they were neighbouring plots. The schedule showed that plot 892 was a ‘Cottage and garden’ and plot 897 was ‘Garden’. Plot 1757 was on another page of the schedule and described as a ‘Cottage allotment’.

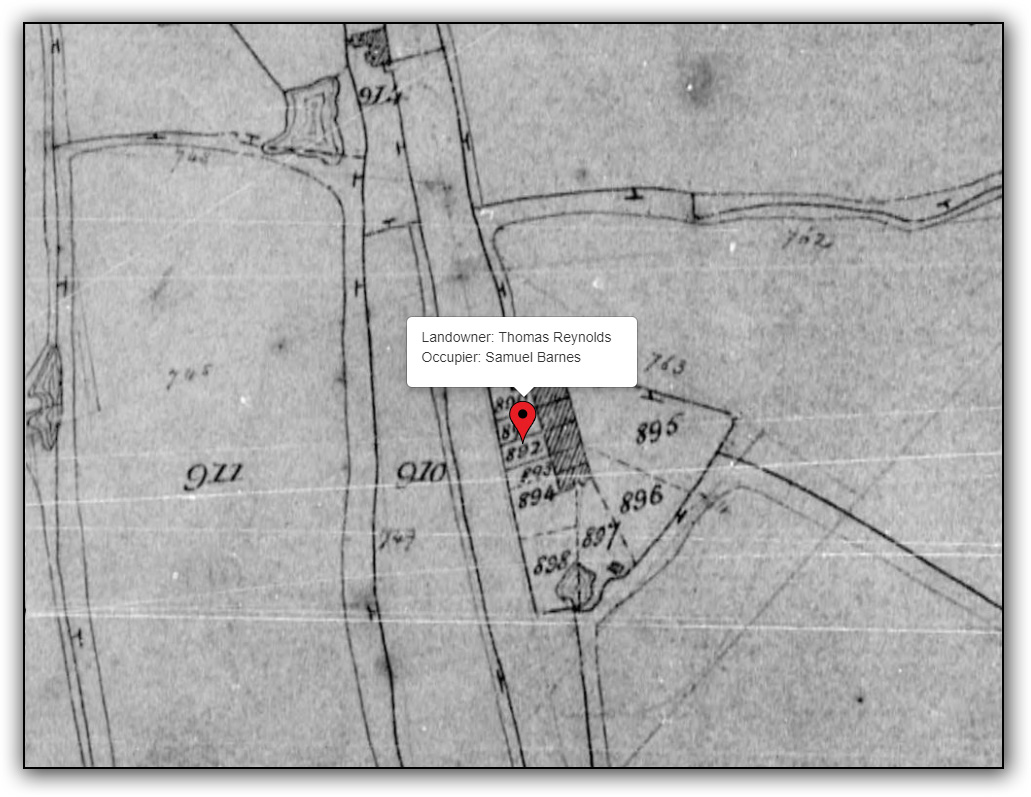

3. I then clicked on the map image to see where each plot was located. Samuel’s cottage and gardens (Plots 892 and 897) were on east side of the main road through Staplehurst leading from Cranbrook to Maidstone. Originally the two halves of Knoxbridge Cottages were situated opposite each other on either side of the road. Those on the east are now called Orchard Cottages. His allotment was about quarter of a mile away and one of a several allotments. Nearby we can see Weeks Farm and a house called Monks and Bennets. Little Brattle Farm and Hog Pound House were also nearby and these helped locate the site of the allotment on a modern Ordnance Survey map.

The tithe records enabled me pinpoint the location of the cottage where Samuel and his family lived and the cottage still stands today. I also gained a better understanding of his life, discovering that, apart from working as a farm labourer, he rented two other small plots of land where he would, no doubt, have grown food to support his large family. The tithe records showed Staplehurst as it was in 1838 when its tithe map was surveyed: a rural town but with two churches and many farm and other large houses, most of which were named on the map. The map also helped me identify the locations of the several manors that made up Staplehurst and this proved useful for locating manorial records.