Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Taking back the prisoners

Nick Thorne researches Sir Robert Napier and the daring 1868 expedition to Abyssinia through inhospitable terrain to rescue British hostages

Tewodros II was Emperor of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) from 1855 until 1868

Taking hostages to try and force a European nation to bow to unreasonable aims is nothing new. In December 1867 the British had to launch a rescue mission for hostages being held in Abyssinia by the unpredictable Emperor Tewodros of Ethiopia. Five years earlier, much of his country had begun to revolt against him. The exception was a small loyal pocket near his fortress at Magdala. Theodore II, as he was known in English, had been engaged in constant military campaigns against an array of rebel countrymen and in an attempt to shore up his rule he had written to the major world powers – Russia, Prussia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, France and the United Kingdom – asking for their help. None replied as he had hoped and this angered him.

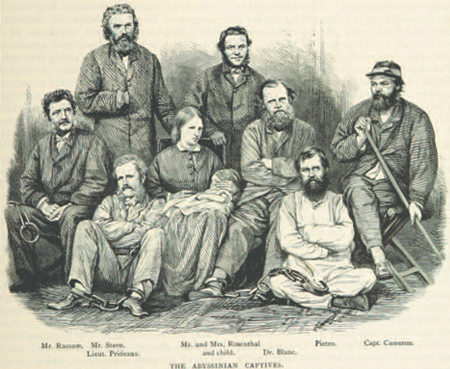

The hostage situation began when a British missionary called Henry Stern was the first unfortunate European to cross Tewodros’ path in October 1863. The Emperor had him taken hostage. Stern had rashly, but with no intention of insulting the Emperor, published a book in which he explained how Tewodros had risen from quite humble origins to have become the ruler of extensive lands. The timing couldn’t be worse as the Emperor was intent on establishing his ancestry from the Solomonic dynasty, considered to have ruled Ethiopia in the 10th century BC and descended from Solomon of Israel. Tewodros had Stern’s servants beaten to death and the missionary and his assistant put in chains for the crime of slighting him.

Diplomacy failed spectacularly when the British consul, Charles Duncan Cameron, and various others fruitlessly tried to intercede on behalf of the men. On 2 January 1864 Tewodros ordered that the consul himself should be seized and, along with all his staff, also be chained. The situation quickly escalated when, shortly after this, the Emperor ordered the shackling of most of the rest of the Europeans in the royal camp for good measure.

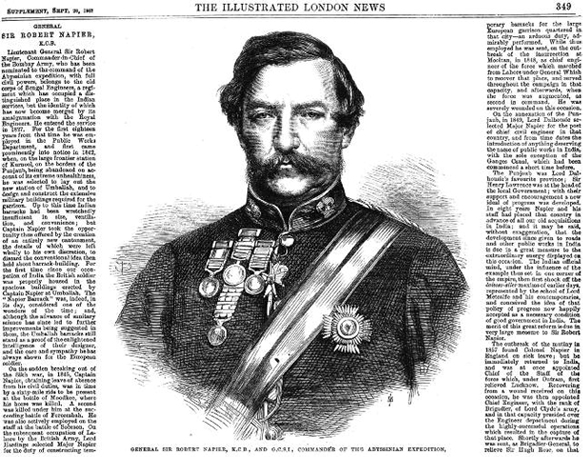

General Sir Robert Napier; The Illustrated London News, September 28th 1867 accessible on TheGenealogist

The British hostages captured by Emperor Tewodros

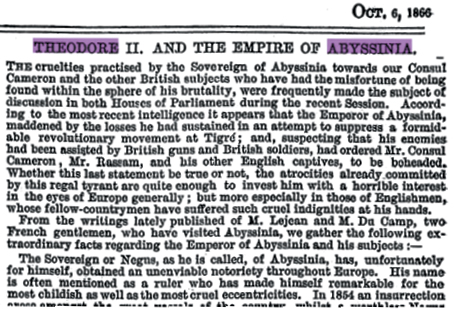

The Illustrated London News 6 October, 1866 retrieved from the Newspaper and Magazine records on TheGenealogist

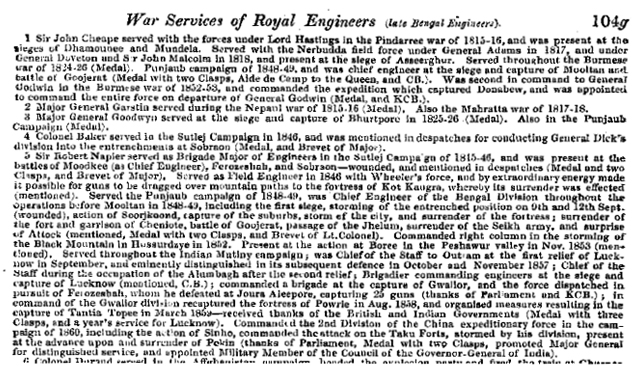

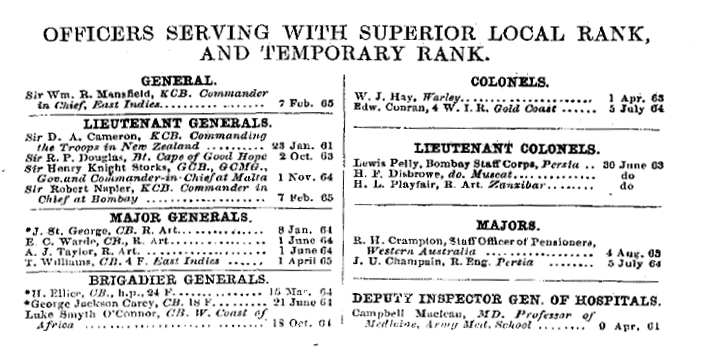

Hart’s Army List for Oct 1863 in the Military Records on TheGenealogist

Tewodros’ brutality was widely reported in the British newspapers. The Illustrated London News on TheGenealogist reveals a report in October 1866 cataloguing various atrocities and portraying him as unpredictably cruel.

Rescue and punish!

The British government’s patience with the Abyssinian Emperor had been exhausted, but what was it to do? Ethiopia was more than 3600 miles away from England. In India, however, the British Empire had a capable army up its sleeves and a commander who believed he could carry out a military rescue mission and punitive expedition to Ethiopia. It would require the transportation of a considerable military force several hundreds of miles across mountainous terrain without proper roads.

General Sir Robert Napier was a particular type of commander, possessing the specialist skills of a military engineer and, as a result of his appointment, this was the first time the command of a campaign was entrusted to the leadership of a graduate of the Royal Engineers Establishment at Chatham. History shows it to have been a most sensible appointment as Napier was victorious in every battle that he had with the troops of Tewodros. Despite the gigantic obstacles in his way he and his troops managed to capture the Ethiopian capital and achieved the safe rescue of all the hostages.

Who was this general? Wanting to find out more about him, I searched the Occupational records on TheGenealogist. and immediately found an entry for Robert Cornelis Napier in The Dictionary of National Biography Vol XIV. This revealed that he was an Indian Army Officer, born in Ceylon the son of an army officer and his wife. Robert Napier’s education was at the East India Company’s Military Seminary at Addiscombe and then in 1826 he was commissioned into the Bengal Engineers and attended the Royal Engineers Establishment at Chatham, Kent to learn his skills. The book reveals that he sailed for India in 1828 and provides a great deal of background information on his life and army achievements, including his participation in the first and second Sikh wars and the Indian Mutiny. In 1860 Napier was appointed to the command of the second division in the expedition to China in the Opium Wars. Among other objectives, he constructed a road in order to cross a mud flat and attack a number of forts which, at the end of the campaign, he and his men destroyed by pulling the structures apart.

When our family research indicates that ancestors served as an officer in the Army, then it is often fruitful to see what can be found in the Military collections on TheGenealogist. In the Hart’s Army List for Oct 1863, as an example, we find Sir Robert’s war service with the Royal Engineers (late Bengal Engineers) recorded. We can see where he served, his promotions and that he had been appointed the Military Member of the Council of the Governor-General of India.

In some cases we may also find that our military ancestors were given a superior local rank over their substantive rank. In the Hart’s Army List for April 1865 on TheGenealogist we can see Sir Robert was listed as Lieutenant General in India.

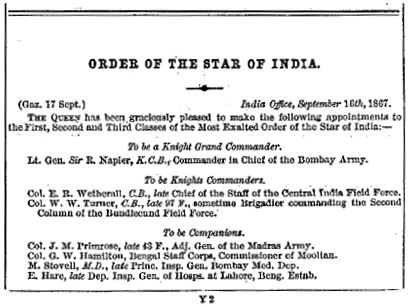

By 1867 Napier had been awarded the Order of the Star of India, which can be found in the Army List for October 1867 on TheGenealogist. It was in this year that his advice was sought on how speedily a force could be equipped and ready to sail from Bombay to Abyssinia. Having already put his mind to the question the General was able to give a quick reply – but it was some time before his advice was acted upon and he was appointed to lead the complicated military operation.

Inhospitable territory

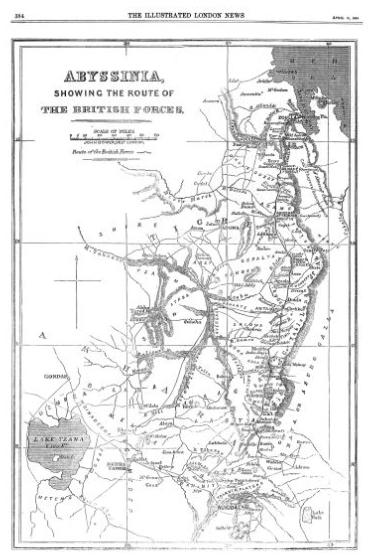

General Napier’s troops sailed from India to land at Zoulah in Annesley Bay on 2 January 1868. Searching the Newspapers & Magazines collection on TheGenealogist we can find various sketches of their campaign including a map of the mammoth route undertook – the rescuers had to march 420 miles through inhospitable territory.

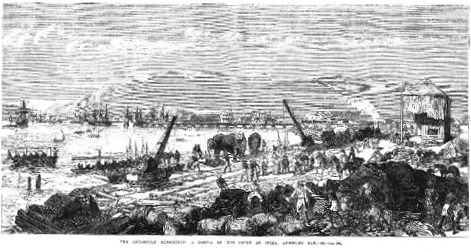

An advance party sailed months earlier and began by building two piers 900 feet long; they also laid down 12 miles of railway to transport men and supplies to the camp inland and had to erect eight rail bridges to do this. Reservoirs were constructed by the military engineers and ship’s boilers were used to condense water to fill the resulting lakes at the rate of 200 tonnes a day. Forty-four trained elephants were brought with the Indian soldiers to carry the heavy guns on the march, while hiring commissions had been dispatched all over the Mediterranean and the Near East to obtain mules and camels to handle the lighter gear that Napier’s 13,000 British and Indian soldiers, plus the 26,000 camp followers, required.

The march to Magdala commenced on 25 January, covering 420 with an elevation of 7400 feet. By 10 April the plateau of Magdala had been reached and the British roundly defeated Emperor Tewodros’ forces there. On the 13th, the stronghold at Magdala was then stormed by Napier’s men and the Emperor was found dead in his fortress. Ironically, the gun he used to take his own life had been given to him as a gift by Queen Victoria herself.

Mission accomplished

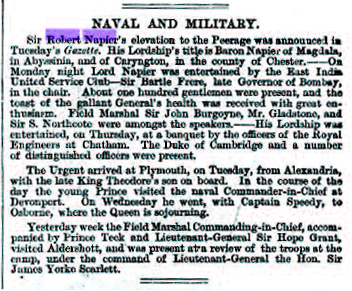

The captives freed, Magdala razed, and the campaign was over. By 18 June 1868 all the men of Napier’s expedition had left Africa to return to India - mission accomplished. A grateful British Empire rewarded Napier for his success – a search of The Illustrated London News 18 July 18 1868 reveals his elevation to the peerage as Baron Napier of Magdala, in Abyssinia, and of Caryngton, in the county of Chester. Fascinatingly, under this piece is a note about the arrival of his erstwhile enemy’s son in Britain. The Prince was being treated as an honoured guest with a visit to the naval Commander-in-Chief at Devonport and then on to meet with Her Majesty Queen Victoria at Osborne House.

In April 1870 Lord Napier was made the Commander-in-Chief, India, with the local rank of full general, achieving the substantive rank of full general on 1 April 1874. He was to die at his home in Eaton Square in London in January 1890. By this time he had been promoted to hold the highest rank in the British Army – that of a Field Marshal.

While this research in the records of TheGenealogist has shown that the taking of hostages is nothing new, it has also uncovered a story of a great military engineer who was skilful enough to successfully plan and execute a mission that others may have thought impossible. And that willingness to take action and achieve results is inspirational to this day.

If in your family research you discover that an ancestor served as an officer in the Army, then it is often fruitful to see what can be found in the Military collections on TheGenealogist.

Hart’s Army List for April 1865 within TheGenealogist’s Military Records

Army List for October 1867 within TheGenealogist’s Military Records

Abyssinia map published in The Illustrated London News 18 April 1868 found on TheGenealogist

The Illustrated London News 21 March 1868 from the Newspaper and Magazine collection on TheGenealogist

Elevation to the Peerage in The Illustrated London News 18 July 1868 and the arrival of Tewodros’ son at Plymouth