Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.The man who built Parliament

Nick Thorne traces the rise of the architect Sir Charles Barry

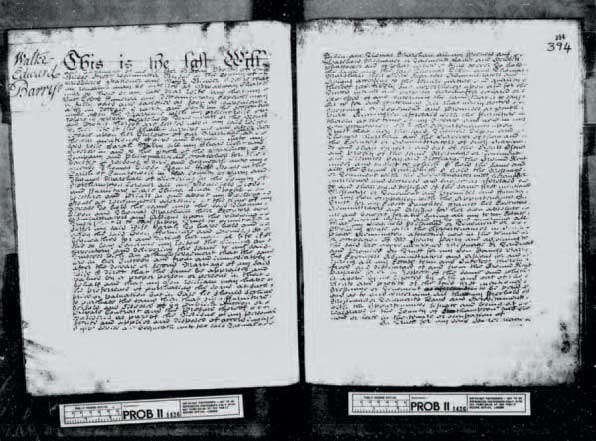

From relatively humble beginnings, Charles Barry rose to be counted among England’s greatest architects, being responsible for one of Britain’s most iconic buildings, the Houses of Parliament. The new Palace of Westminster was first erected on the site after fire had destroyed two-thirds of the old buildings on 16 October 1834. The destruction spared only the ancient Westminster Hall, the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft (which had been completed in 1297) and the Cloisters. After the blaze a competition was held in 1835 for a new palace to be built and 97 entrants applied. The competition was won by the 40-year-old architect Charles Barry in 1836 and he involved the help of another famous name from British architecture, the 23-year-old Augustus Welby Pugin, to provide the detail drawings. It was Pugin who is credited with designing most of the grade I building's magnificent Gothic interiors, including panelling, carvings and gilt work. Pugin, it is widely reported, was not, however, a fan of the resulting exterior. Searching for information on Charles Barry we can discover him and his wife Sarah in the 1841 census on TheGenealogist. Charles is shown as being 46 and Sarah is 42 and they are living at Foley Place in Marylebone.

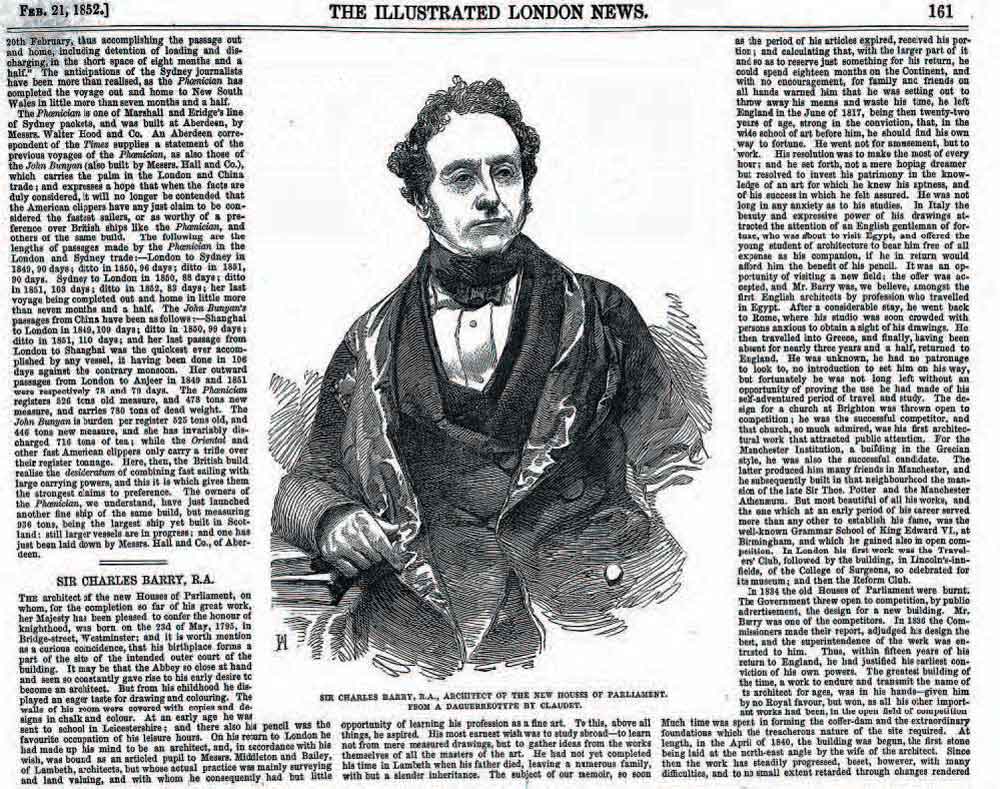

In the Newspaper & Magazines collection on TheGenealogist we can find an article in The Illustrated London News for 21 February 1852 that gives a lot of background information on Sir Charles Barry, as by the time of publication he had now become. We learn that he was born on 23 May 1795 in Bridge Street, Westminster. The newspaper considered it worth a mention that this address was now part of the site and that in Barry’s plans the outer court of the Houses of Parliament would cover over his family’s former home.

The Illustrated London News for 21 February 1852

Son of a stationer

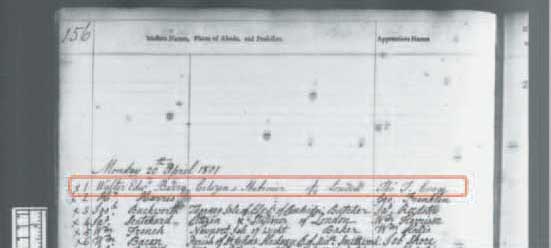

Charles was the fourth son of Walter Edward Barry, a stationer in Bridge Street. In the occupational records on TheGenealogist we can find a number of apprenticeship records in which the elder Barry is recorded as the Citizen and Master providing apprenticeships to various men.

Charles Barry’s father appears as the Citizen and Master in a number of apprenticeship records

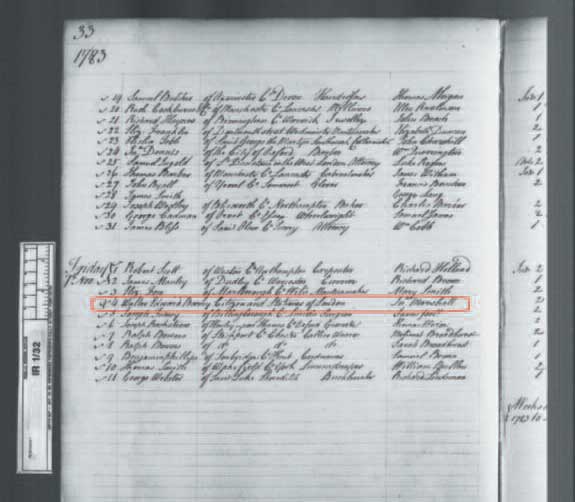

The young Charles was himself bound as an articled pupil to Messrs Middleton and Bailey of Lambeth, though it seems that their practice was more in the line of surveying. When he had completed his time with Middleton and Bailey and having inherited a small amount of money on the death of his father, he embarked on a tour of Europe to learn about classical art. The Illustrated News article reported that this was against the advice of family and friends who feared he would be throwing away his capital. A search of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) wills, on TheGenealogist, reveals the will of Walter Edward Barry, Stationer of Bridge Street proved in June 1805 from which the young architect inherited his legacy that enabled him to complete his education. The decision to use his inheritance in this way paid off because he soon began to win various competitions to be selected as the architect for a number of buildings. His first to attract public notice was a church in Brighton, followed by the Manchester Institution and some time later the King Edward VI Grammar School in Birmingham.

The 1805 will of Walter Edward Barry, Stationer from PPC wills on TheGenealogist

By 1835 and with another competition won, he was now in charge of designing one of the most significant buildings in the world. Areport in The Illustrated London News for 8 May 1847 details the exchanges between various Members of Parliament discussing a vote of funds for the new House of Commons and complaining of the enormous amount spent on the decorations of the new House of Lords. As today, it seems, the worry about expenditure running away over the original estimate was a major concern even then, the committee in charge having sanctioned many deviations from the early plans.

Barry’s Palace of Westminster showing Bridge Street, Westminster the onetime birthplace of the architect

The Illustrated London News of 4 May 1850 reveals differences between the architect and that person in charge of ventilation leading to an action for defamation

M.P.s concerned by the expense of building the new Houses of Parliament in The illustrated London News 8 May 1847

Costs Spiral!

The construction of the new palace had begun in 1840 at which time Charles Barry had estimated a construction time of six years and at an estimated cost of £724,986. According to a present day government website, the project in fact took more than 30 years and at a cost of over £2 million; but a piece written in Sixty Years a Queen, a reference book on Queen Victoria’s reign published in 1897 and found on TheGenealogist, speculated that it may have been closer to £3m at that time.

Sixty Years a Queen from the Reference books on TheGenealogist

The exchange between the MPs introduces us to a Dr Reid, in charge of ventilation for the new Houses and whether he was to be allowed to go on without regard to expense. While one member seemed to insinuate that both Barry and Reid only consulted their own glorification in deciding the work needed. Lord Morpeth, however, spoke of the two men being granted some discretion by the House and arranging a plan to see it carried out. While that sounds admirable, a further look at the resources in the Newspapers and Magazines on TheGenealogist reveals that the two men did not function in harmony. The Illustrated London News of 4 May 1850 refers to differences between the architect and Dr Reid over ventilation. It had got so bad that the committee had been frustrated in all its efforts to bring about a reconciliation between the two and that Mr Barry was about to commence an action for defamation of character against Dr Reid! One MP, Mr B Osborne, was so fed up with the two men that he gave notice that he would bring an early day motion to get rid of them both.

Researching further and another article, in 1848, gives us an idea of what Dr Reid had to contend with regarding the site. It was probably not a case of just removing the hot air produced by the numerous members of the legislature in their daily pontification, but also the foul smells from the drains below. The Illustrated London News of 21 October for that year explains that the main sewers passed under the entire length of the building before emptying into the Thames. This conduit was so filled with fetid and flammable gas that an inspection recommended that and unless speedily remedied the situation might involve very serious considerations.

The Illustrated London News 21 October 1848

The two protagonists

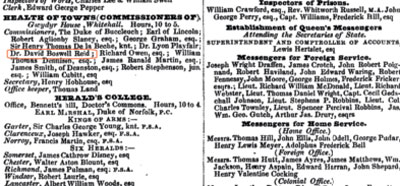

A search of the Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories on TheGenealogist discovers the importance of each of the players. An entry for Dr David Boswell Reid in the 1846 Kelly’s Post Office Directory discloses that he was one of the Commissioners of the Health of Towns whose offices were at Gwydyr House in Whitehall. While a search in the same directory finds an entry for Charles Barry RA, Architect. He had been elected a Royal Academician in 1842, joining what was an exclusive membership of only forty RAs in that period. Another Kelly’s trade directory, this time for 1869, lists Barry as a Vice-President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. We may wonder which of the powerful personalities won and a search for some sort of resolution is provided by a paragraph in the newspapers for 1853 when Sir W Molesworth replied to a question in the house. The unfortunate Dr Reid had been removed from his office by the late Government. His demand for £10,250 compensation had gone to arbitration and he had been awarded only £3240.

1846 Kelly’s Post Office Directory

Kelly’s Post Office 1869

Sir Charles Barry, then, had won the tussle and was able to appoint his own man to replace Reid. He was not, however, left to complete his full scheme as he had designed it. To this day the full Barry design was never accomplished. According to his biography – The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry RA, FSA, published in 1867 by John Murray and written by one of his sons, the Rev Alfred Barry – Sir Charles’s design would have enclosed New Palace Yard as an internal courtyard. He would have also placed the famous clock tower in the north-east corner, built a great gateway in the north-west corner which would have been crowned by the Albert Tower and then continued his Palace of Westminster to the south along the west front of Westminster Hall.

While Sir Charles’s building was not completed, as he had originally envisaged, the result is a much loved structure that is instantly recognisable across the world as the home of the Mother of Parliaments. Very few architects would have had the opportunity of leaving a legacy of an icon in the neighbourhood of their birth and certainly not one that has been captured in countless paintings, photographs and sent as postcards to the far corners of the world.

The Illustrated London News 21 May, 1853 Dr Reid had been removed and awarded significantly less compensation than he had claimed.