Your Family History

Your Family History was published by Wharncliffe Publishing Limited. It has now ceased publication.The Stanfield Hall murders

Nick Thorne looks at a case from the archives, where a landowner and son were killed by a disgruntled tenant.

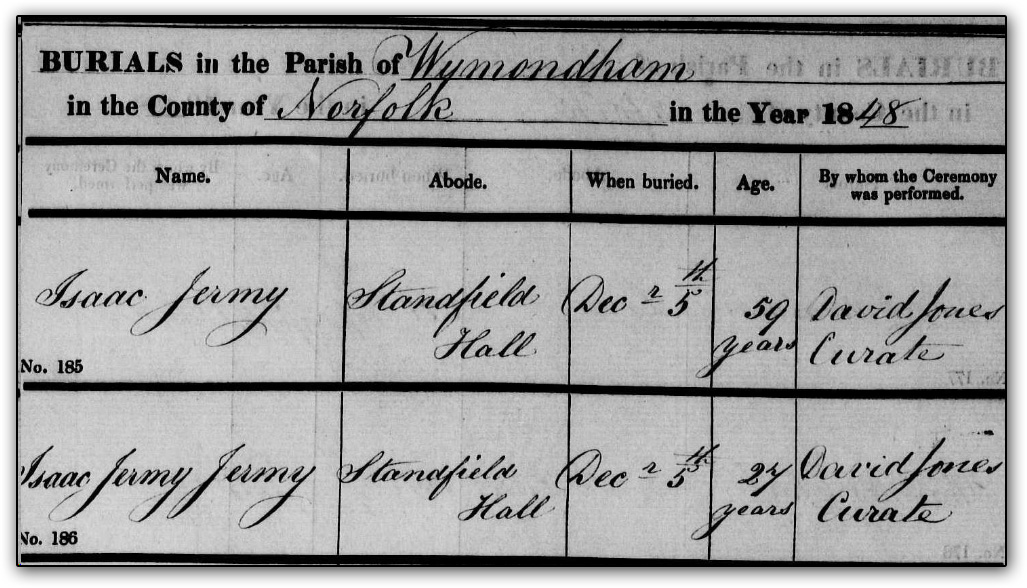

I was browsing the recently released Norfolk parish records on The Genealogist when, in the parish of Wymondham, I came across an intriguing entry of the burial on the same day of two men with almost the same Christian and surnames: Isaac Jermy and Isaac Jermy Jermy. Immediately my curiosity was roused, and I wondered what the story was behind these burials. My intuition told me that it was likely to be the result of a tragedy – from their ages, 59 and 27, and the fact that their abode was the same, I thought they were likely to be father and son.

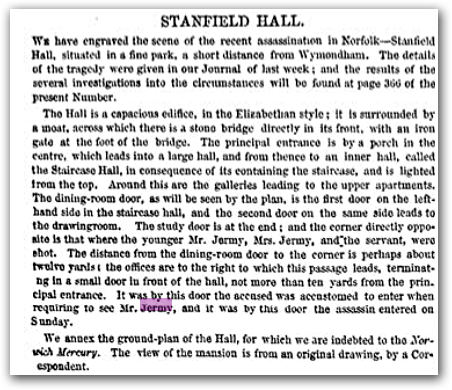

Where you are able to see an original page of a register; such as in the case of the Norfolk parish registers, you may be treated to a note made in the margin by the clergyman that reveals a bit more information Sadly, though, the curate, on this occasion, had not felt it necessary to give any aid to the curious researcher of the future. The clue to unravelling the mystery, however was the place of abode that was neatly written – although incorrectly spelled – in the parish register. A search for the names of the deceased in The Genealogist’s Newspapers and Magazines collection revealed a story the Illustrated London News about the Stanfield Hall Murders – the shooting of both father and son in their home one November evening in 1848.

Change of name

The report, whilst not revealing much about the circumstances of the double murder, introduced a conundrum. Why, I wondered, did the elder Isaac Jermy’s sibling and the deceased not share the same surname? The brother went by the name of Mr Thomas Preston of Lowestoft, so I wondered which of them had changed their name, or whether they were half-brothers. I found the answer as soon as I looked the family up in TheGenealogist's Peerage, Gentry and Royalty record collection.

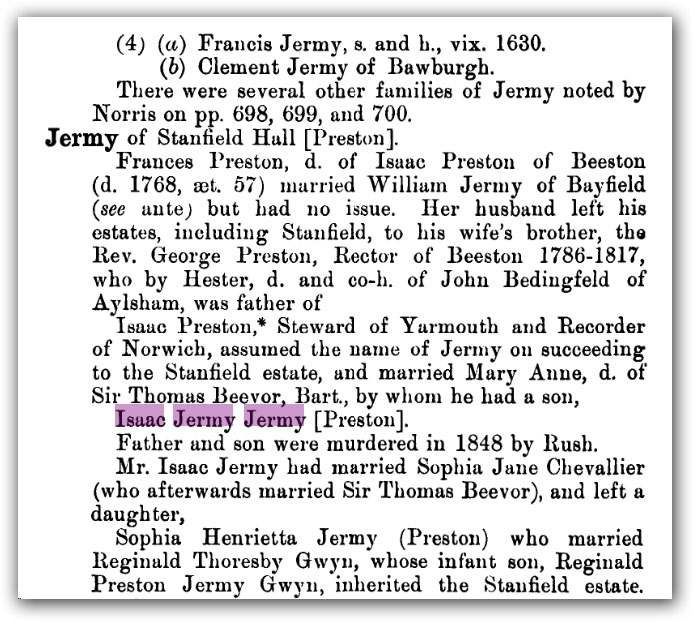

An entry in the digitised book Norfolk Families revealed that William Jermy of Bayfield has taken as his second wife Frances Preston, daughter of Isaac Preston of Beeston. The couple had no children, so on William’s death, his property passed to his wife’s brother, the Rev George Preston. It was this clergyman’s son who, named Isaac Preston after his grandfather, was destined to be the elder victim of the murderer. Isaac, having inherited Stansfield Hall, then assumed the surname of Jermy. The reason for his change of name was to comply with a clause in William Jermy’s original will that the estate should pass ‘to the male person with the name Jermy nearest related to me in blood, and to his heirs forever.’ Isaac Jermy, formerly Preston, being a lawyer by profession, simply complied with the letter of William Jermy’s will. Isaac held the important positions of Steward of Yarmouth, and as the Recorder of Norwich, was a part-time circuit judge.

The short summary in Norfolk Families of how Stanfield Hall came into Isaac’s ownership may have been an oversimplification – it seems the inheritance had been challenged. Evidence of this was found in newspaper records on TheGenealogist – on 9 March 1850, there was a short piece referring to men named Jermy and Larner gaining entrance to the now empty and tenantless hall and taking possession of it, having previously put forward claims to the estate.

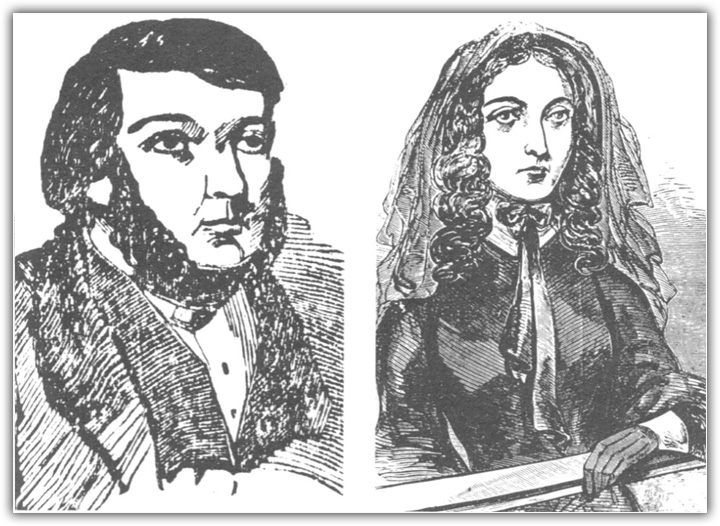

James Bloomfield Rush and Emily Sandford in 1849

The Norfolk murder case was covered in the Illustrated London News on 9 December 1848

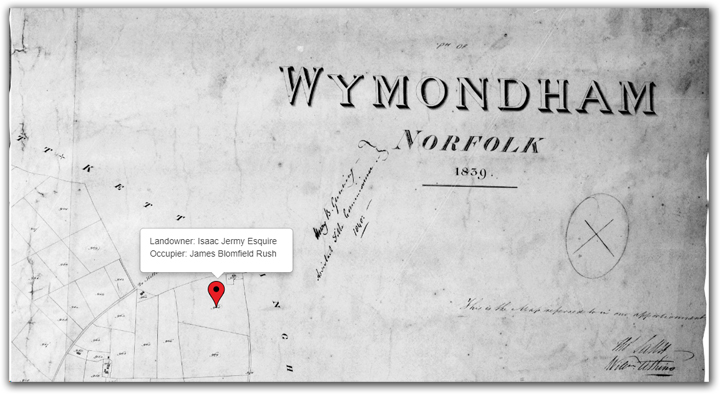

One of the many plots leased to the murderer Rush by his victim Isaac Jermy

The Norfolk murder case was covered in the Illustrated London News on 9 December 1848

Land Dispute

On 2 December 1848, the Illustration London News had revealed that James Blomfield Rush and Isaac Jermy had been involved in a law dispute, Rush had borrowed money from his landlord to buy another farm, but was unable to repay the mortgage and was also in debt to his bankers. I was aware that the parties were landowners and occupiers at a time when the government was in the process of reforming and replacing the ancient system of payment of tithes in kind with monetary payments. I therefore turned to a search of the tithe schedules and maps on TheGenealogist and was able to see that Rush, who was accused of the murders, occupied land that was owned by the elder Isaac Jermy.

James Rush had become the land agent to the family in the Reverend Preston’s time, but despite being loaned money by Isaac Jermy, the two had a difficult relationship. When Isaac took over his inheritance, he decided to advertise the sale of books from the hall’s library in order to fund the refurbishment of his home. This was brought to the attention of the men who later claimed they were the rightful heirs. They believed that Isaac was breaking one of the terms of the original will of the former owner. Rush, meanwhile, was overstretched by his own farming interests. These included arrears on the mortgage for his farm – one he had bought for himself when he was supposed to be buying it for Isaac. He was the prime suspect for the murders, but tried to put the blame on the estate’s claimants by forging incriminating documents. Unfortunately for him, these documents were signed in the name of a claimant who was illiterate, and could not have been the murderer.

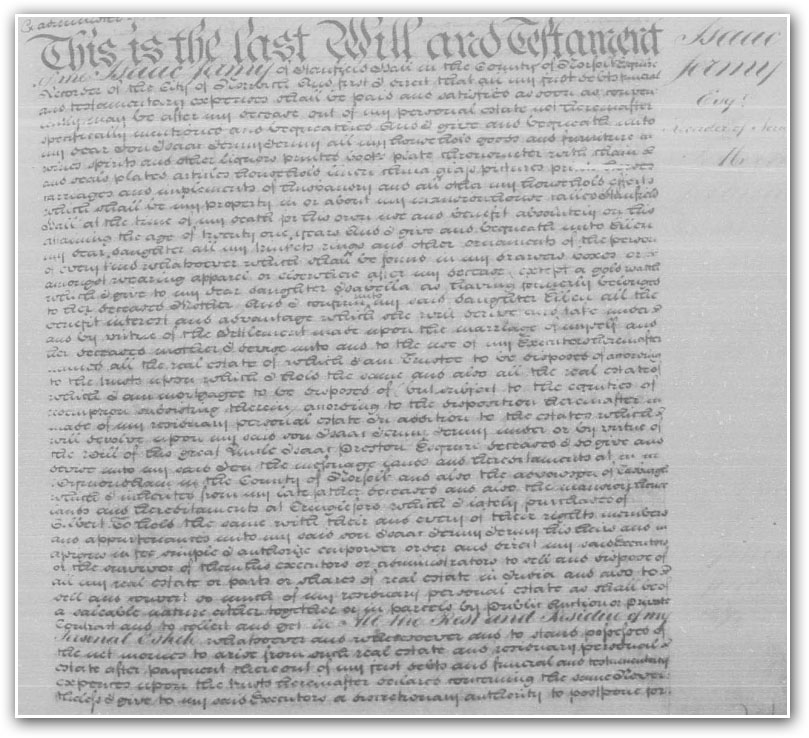

Rush had carried out the shootings of both Isaac Jermy senior and his son whilst in disguise, aiming to conceal his involvement in the crime. A servant he had wounded, however, recognised his bearing and gave evidence to the court to this effect. At trial, the nefarious farmer was convicted after a very short deliberation by the jury, and sentenced to death. James Blomfield Rush’s public execution was carried out in front of Norwich Castle on 14 April 1849. TheGenealogist has lots of records relating to this family. These include the last will of the unfortunate late Recorder of Nowich, Isaac Jermy, in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury wills section. From reading the document we can see that he had intended his son, Isaac Jermy Jermy, to inherit his estate. Instead the Dictionary of National Biography, also on TheGenealogist, shows that Isaac Jermy Jermy’s daughter Sophia Henrietta ended up inheriting Stanfield Hall. When she married Captain Reginald Gwyn, the hall and estate passed into his family. TheGenealogist has a whole host of different record collections ranging from parish, landowner and occupier records, newspapers and magazines, to the digitised books of nobility and gentry. These have all helped reveal the story of the murders at Stanfield Hall.

The will of Isaac Jermy, which can be found on TheGenealogist's website

The burial register for Wymondham – part of The Genealogist’s release of Norfolk parish registers, in partnership with Norfolk Record Office