Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.The Wills Forgery Trials

Nick Thorne considers a case of forged records that had a lawyer wrongly transported for life

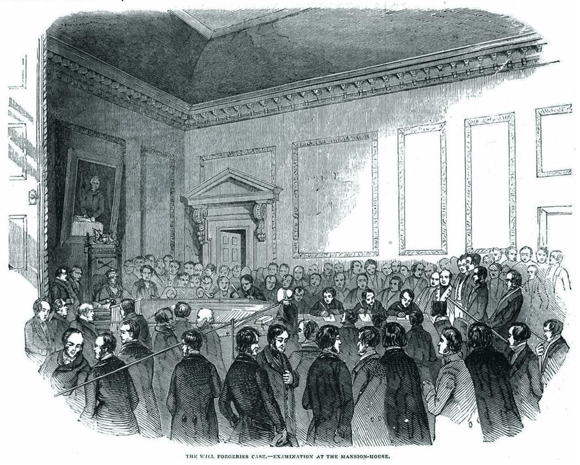

Before the Mayor at the Mansion House in the City for the investigation

When researching our ancestors after 1837 in England and Wales, we generally try to find their birth, marriage and death in the government-compiled civil registration records and assume that they will be accurate records of the events. Likewise we don’t expect there to be any rogue forgeries in amongst the wills that have been proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. In most cases, thankfully, the records are correct reflections of our ancestor’s life events and we can enter the details in our family tree. But, as with all aspects of life, sometimes a person with criminal intentions may seek to dupe the official entering the details into the records and this has a knock-on effect on the innocent family history researcher who may come across such a forgery.

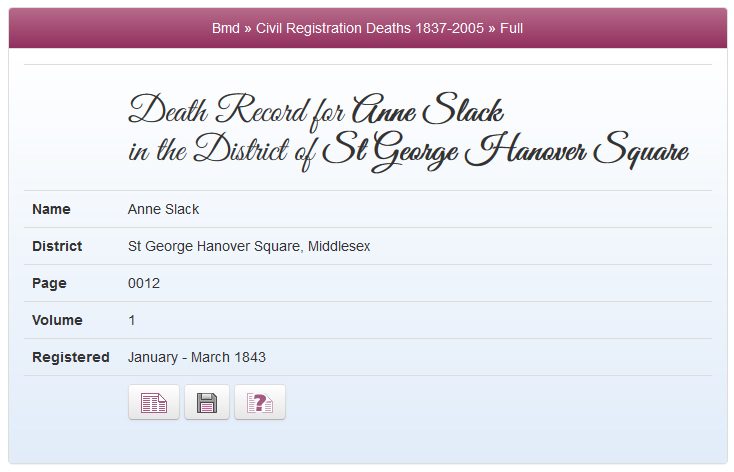

A law change in 1874 tightened up the previous position whereby a medical certificate hadn’t been required by the registrar at the time of registering a death. An informant’s word had been quite sufficient for the procedure to take place and so it was this lack of evidence that enabled an unscrupulous group of people to take criminal advantage of the process. This was what happened in the case of Miss Anne Slack. Her death was incorrectly reported to the registrar in the upmarket London district of St George, Hanover Square. From a look at the General Register Office records on TheGenealogist we can see that an official death record for the unfortunate lady still exists in the GRO index for the first quarter of 1843.

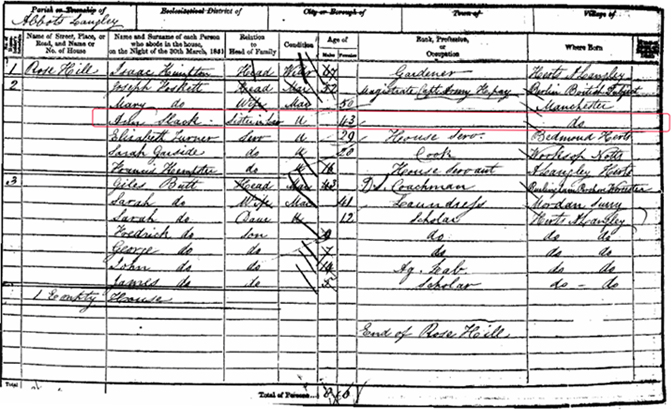

In truth, Anne Slack was alive and well and living at the time with her sister, Mary, and her brother-in-law Captain Foskett in Abbots Langley, Hertfordshire. She was still with them by the time of the census in 1851, as can be seen from a search of the records on TheGenealogist.

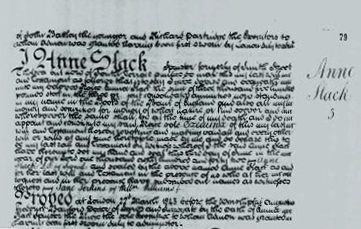

The conspirators in the crime constructed a story that Anne Slack had been a spinster, aged 72, formerly of Smith Street, Chelsea, and lately living at the fictitious address of South Terrace, Pimlico, whereas the real Anne Slack was a spinster, aged about 36 in 1843. Though she had indeed lived at Smith Street in Chelsea until 1830, she was now living with the Fosketts in Hertfordshire. The criminals had got a forged will drawn up and then presented it to the office of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC). The PCC, not realising that the will was not genuine then granted probate, allowing the will to bequeath ‘£3,500 three per cent Consols’ (consolidated stock) to an Emma Slack, the supposed niece of Anne. One of the prisoners before the court was Mrs Lydia Sanders who had purported to be Emma Slack to gain the money for the co-accused.

Some years earlier, in 1829, an entry had been made in the books of the Bank of England in the name of ‘Anne Slack, of Smith-street, Chelsea, spinster’. It was for two securities, one of which was for over £6,600 in 3% annuities, and the other for £3,500 in the 3% consols. Both had been purchased on 23 October 1829 with the dividends being paid to a Mr Hulme, who had a power of attorney for Miss Slack up to January 1832 as her father’s executor and the lady’s guardian. All was well with Anne Slack receiving her dividends from her guardian until his death in 1832. She was then paid directly the dividends for the first holding herself. Unfortunately Miss Slack was unaware of her ownership of the later security and so didn’t claim them for almost ten years. Because the dividends for the 3% consols were not being claimed on 6 July 1842, the authorities then transferred the securities to the Commissioners for the Reduction of the National Debt and published a list of unclaimed securities.

Death record for Anne Slack 1843 in the district of St George, Hanover Square

Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) will for Anne Slack 1843 on TheGenealogist

1851 census of Abbots Langley in Hertfordshire

The trials

This was the background to the case that attracted much of the public’s interest in 1843 and 1844. Reports on the proceedings are to be found in The Illustrated London News, within the Newspapers and Magazines records on TheGenealogist. Here we find the gang in December 1843 at their committal in the court at London’s Mansion House before they are sent for trial on the count of forging a will of Anne Slack at the Central Criminal Court. The prisoners at the bar included a solicitor called William Barber and a surgeon, Joshua Fletcher.

The defendants had first to appear before the Lord Mayor of London at the Mansion House for the magisterial investigation that preceded the trial. Solicitors for the Bank of England appeared in the prosecution of the first case. It then emerged that there was a second charge being brought against the very same individuals, for forging the will of a woman from Bristol named Mary Hunt. A search of the PCC wills on TheGenealogist discovers the probate record for this fraudulent document also hiding in amongst all the other more bona fide wills.

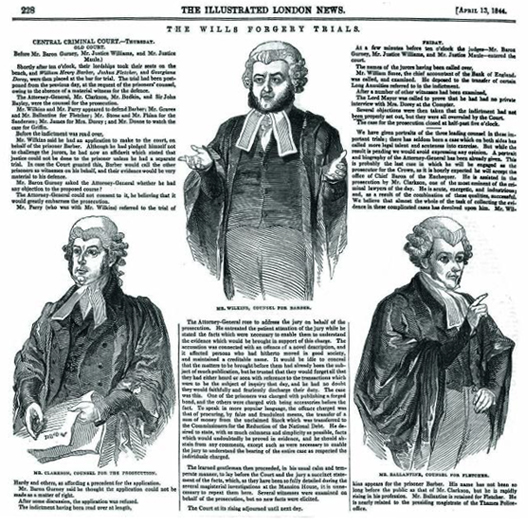

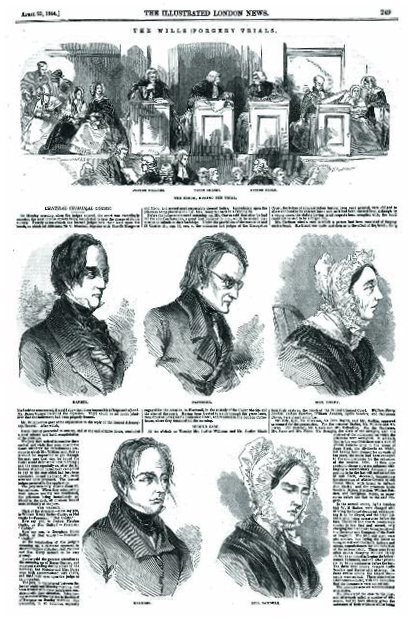

It was in April 1844 that ‘The Wills Forgery Trials’, as the press named them, reached the Old Bailey. Searching the newspapers and magazines collection on TheGenealogist finds the artist for The Illustrated London News had decided to provide pictures of the three defence barristers for their readers to view in their 13 April edition – but they omitted sketches of the accused. This situation was rectified in the 20 April edition when images of all the prisoners were published that showed interesting looking characters, none of which are particularly flattering portraits, and included three more defendants.

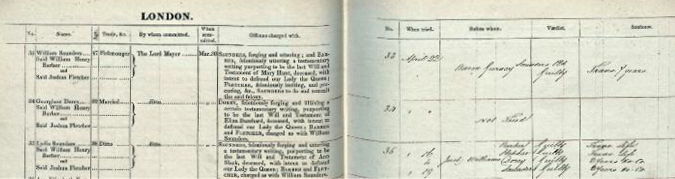

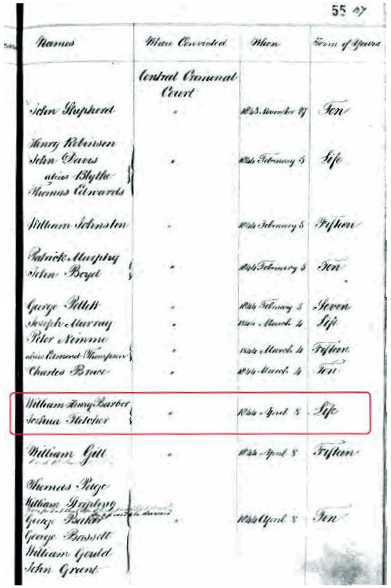

The first case heard was that concerning the will of Mary Hunt of Bristol. Lasting over several days, when it came time for the jury to retire it was for all of 15 minutes before they came back with their conclusion. They returned a verdict of not guilty on the solicitor, William Barber, and guilty for Fletcher and Mrs Dorey. Barber was reported by The Illustrated London News to look calm and the other two prisoners seemed very gloomy. But William Barber was not free to go. On the next day the court then launched into the second trial, the case concerning the forged will of Anne Slack with Barber, Fletcher and a married couple, the Sanders standing accused. The evidence was presented, the defence offered, and the trial ended this time with a verdict of guilty for the solicitor, William Barber. The surgeon, Joshua Fletcher, and Mrs Georgiana Dorey and Mrs Lydia Sanders were also found guilty but Sanders’ husband, William, was deemed not guilty of this crime. Earlier, however, as we will see from the records on TheGenealogist, he had pleaded guilty in the first case before the Old Bailey and would be sentenced to transportation for seven years. By searching the Court and Criminal records on TheGenealogist we are able to find the Newgate Prison Calendar with the verdicts written in by hand next to the printed details of the prisoners and the offence.

The Illustrated London News 13 April, 1844

Newgate Prison Calendar from the Court and Criminal records on TheGenealogist

The Illustrated London News 20 April, 1844

Court and Criminal records: Transportation July 1844

Transportation for life

Barber and Fletcher were given tougher sentences: transportation for life. The women, on the other hand, were incarcerated in an English prison for two years each. The press reported on the prison van arriving at Millbank Penitentiary from Newgate with Barber, Fletcher and Saunders onboard. They also revealed that a transport ship was fitting out in Woolwich and was expected to sail within weeks with these convicts as unwilling passengers to the Australian penal colony. In July 1844, while the former solicitor and surgeon were now on board the transport ship Agincourt as she waited for departure, Fletcher wrote a document that was witnessed by an officer of the convict vessel. In it Fletcher claimed that William Barber had no guilty knowledge of either crimes. It was not enough, however, to prevent the convicted lawyer from sailing for Norfolk Island as we can see from the records on TheGenealogist where their names appear in the Convict Transportation Registers. There is also a report in The Illustrated London News documenting their sailing on the Agincourt on 13 July 1844.

The twist

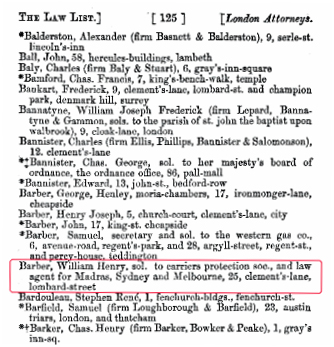

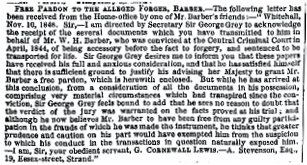

A search of the occupational records on TheGenealogist for lawyers, some 12 years later, finds a solicitor with the name William Henry Barber. Apart from his other entries, it details that he was a law agent for Madras, Sydney and Melbourne. Was this the same man that had been convicted in the Wills Forgery Trials? His full name is the certainly the same. Bearing in mind that a sentence of transportation was a one-way passage, it would seem unlikely that he could have returned and resumed his legal practice and yet further investigation reveals that in December 1846 The Illustrated London News reported that Barber was awarded a free pardon but on the condition that he didn’t return to England. Then in November 1848 he was given a Free Pardon by the Secretary of State at the Home Office, Sir George Grey. The 18 November 1848 edition of The Illustrated London News reported the decision and also the Home Secretary’s thoughts that if Barber had been more prudent and cautious in his business then he would not have fallen under suspicion. Sir George was at pains, however, to record that the jury’s verdict had been justified on the facts known at the time of the trial.

Searching the Trade, Residential and Telephone directories we can find William Barber, solicitor, in 1859 at an address in the City of London. Further research has shown that in 1855 William Henry Barber had been reinstated as an attorney and in 1858 various MPs moved for compensation to be given to the pardoned lawyer.

While your ancestors’ records have probably not been adulterated by criminals, the story of the Wills Forgery Trial has shown us how we can find death records, wills, newspaper articles and criminal records by using the resources of TheGenealogist.

PCC will for Mary Hunt of Bristol

The Illustrated London News 30 December 1843

The Law List 1856 from the occupational records on TheGenealogist

November 18, 1848 The Illustrated London News: Free Pardon