Discover Your Ancestors

Two critically acclaimed publications are available to family history researchers - the annual print magazine, Discover Your Ancestors, and the monthly online magazine, Discover Your Ancestors Periodical. Click here to subscribe.Unconventional lives

Nick Thorne delves into the archives to demonstrate that our forebears had complicated lives just as we do

It can be tempting to think that our ancestors were very different from us, that they were more straight laced and that unmarried couples living together is a totally modern-day phenomenon. Our research, however, can sometimes find that not all of them conformed to the norm. Some married a person much older or younger than themselves, while others were not wed at all.

Recently, I came across an interesting bunch of people while looking at the family of an aristocratic army officer. The gentleman in question was General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe. Together with Charlotte née Clare, he had nine children altogether. The couple’s offspring had birth years that ranged from 1857 for the eldest, a girl named Mary Kate, to 1876 for the youngest, a boy called Patrick. But there was something strange about this family.

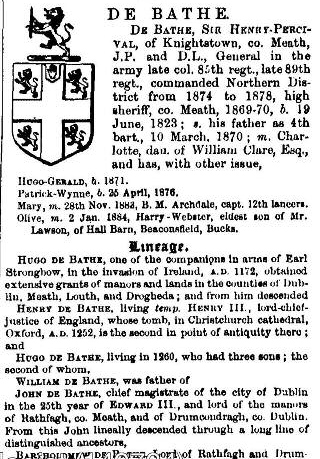

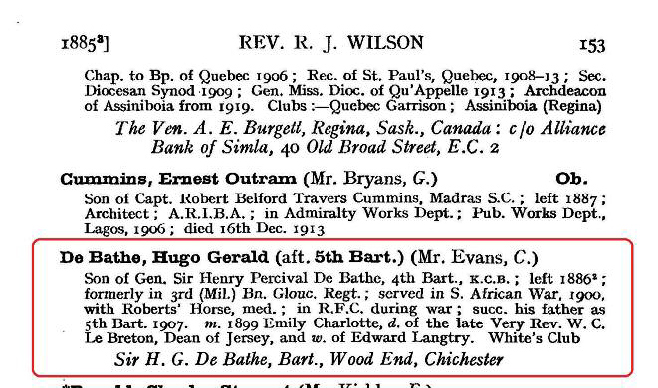

What intrigued me, when looking at the de Bathes, was why Sir Henry de Bathe’s baronetage jumped two sons to pass to his third. His heir, Hugo, was born in 1871 though the eldest son had been born 11 years earlier. It was not that the elder two sons had died, so why hadn’t the first son, Henry, whose birthdate had been back in 1859, inherited? Between Henry and Hugo, as well as a number of sisters, there was another brother named Maximilian. It was strange, therefore, that the title jumped to the younger Hugo. This may at first seem to be somewhat odd. It is a normal principle of primogeniture that sons inherit before daughters, which explains why all Hugo’s sisters were passed over. But it is normally the case that older male children inherit before younger ones.

Some readers, however, may already have realised that the reason that Hugo inherited instead of his elder brothers was that the first seven children born to Henry and Charlotte were in fact illegitimate in the eyes of the law. At the time of their births, the parents had yet to marry because their union had been frowned upon by the general’s father, who was at the time the 3rd Baronet.

From the records on TheGenealogist we are able to find that the marriage between Henry Percival de Bathe and Charlotte Clare took place in the last quarter of 1870. A search of Burke’s Peerage within the Peerage, Gentry and Royalty records on TheGenealogist finds that Sir Henry de Bathe had succeeded his father, Sir William, to become the 4th Baronet on 10 March of that very year. The death records on TheGenealogist also confirm that Sir William had died in Westbourne Sussex in the first quarter of 1870 at the age of 76. Now we can see more clearly that the death of Henry’s father and his own ability to marry were related.

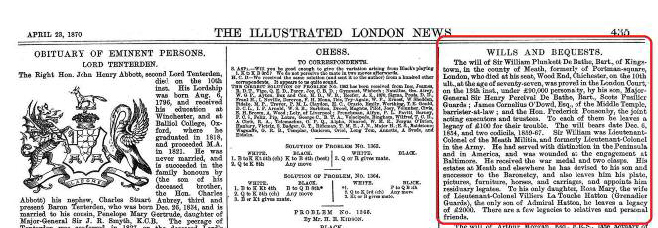

The Illustrated London News of 23 April, 1870 published a precis of Sir William’s will and bequests. Researching deeper into the family story and we discover written accounts online that the 3rd Baronet had certainly disapproved of the match that his son had made and so it was only after Sir William had died that Henry, now Sir Henry, de Bathe and Charlotte Clair could marry. At this juncture they had been living together for almost 13 years and went on to produce Hugo in 1871 and then Patrick in 1876. In the eyes of the law these two were the only legitimate offspring of the couple until the passing of the Legitimacy Act in 1926 then offered the others an opportunity to apply to the courts to be recognised as legitimate. In spite of this, however, it would not affect the succession of the baronetage which had already passed to Sir Hugo de Bathe in 1907.

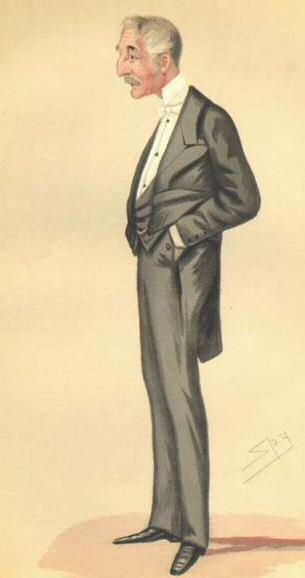

General Sir Henry Percival de Bathe by Spy, published in Vanity Fair, 18 November 1876

Burke’s Peerage in the Peerage, Gentry and Royalty records on TheGenealogist

The Illustrated London News 23 April, 1870

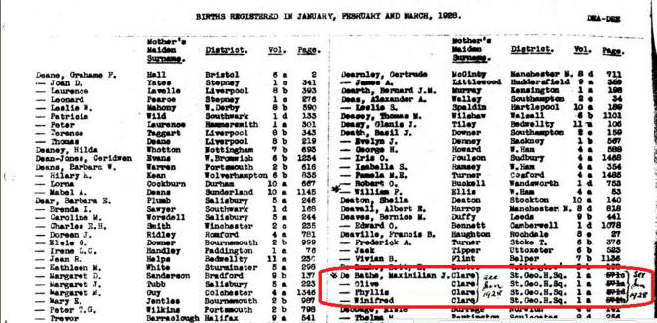

Civil Birth Index on TheGenealogist recording the re-registration of some of the de Bathe children in 1928

Lillie Langtry from TheGenealogist’s Image Archive

Recognised as legitimate

With the Legitimacy Act 1926 on the statute book children could become legitimate by the subsequent marriage of their parents, provided that neither the husband or the wife had been married to a third party at the time of the child’s birth. The High Court could legitimise the birth and instruct the General Register Office to re-enter in the birth indexes for that year the person’s details, even though many years may have passed from their original birth date. The original entry would then be annotated to refer to the new entry. The 1926 act was then modified by the Legitimacy Act 1959, which then extended it to children whose parent(s) had been married to somebody else when they were born, but had subsequently legally married.

In the case of the de Bathe children, just four of the seven children, born before their parents had married, applied to the High Court in 1928 and were thus legitimised. We can see that Olive, Phyllis, Winifred and Maximillian appear in TheGenealogist’s Civil Birth Index for the year 1928 despite all having been born in the 1860s. By the time they are recorded in the GRO index Olive de Bath had married and was now the Viscountess Burnham; likewise Phyllis de Bathe had become Lady Somerleyton and their sister Winifred de Bathe was married to the racehorse owner and politician Colonel Harry McCalmont.

The heir and the actress

Hugo, the heir to the baronetcy, was 28 years old when he got married in July 1899 and his choice of partner would be unconventional. His bride, Emilie, was in her mid-forties. She had been married before, carried on very public affairs and been divorced, and then her former husband had died in an asylum.

Soon after their wedding Hugo volunteered to fight in the Boer War joining the Robert’s Horse regiment, a fact we can establish from looking at the St Peter’s College, Radley Register in the Educational Records on TheGenealogist. His new wife, known to all as Lillie, was the daughter of the Very Reverend William Le Breton, an Anglican clergyman who had been appointed as the Dean of Jersey. While her father may sound quite respectable on the surface, the dean, however, had a reputation as a womaniser and had even initially eloped to Gretna Green with Lillie’s mother, also named Emilie, before marrying in the Church of England church of St Luke’s Chelsea in London. Producing seven children, the clergyman continued to philander after his marriage and ended his days banished to a poor parish in London. Dean Le Breton died some ten years before his daughter took her second husband, though she and Hugo returned to the church of St Saviour’s in Jersey to take their vows. This had been where her father had once been the incumbent in the years when she had been growing up.

The bride’s late father’s womanising were not the only scandals associated with Hugo’s new wife. Lillie Langtry was already famous across the world as a one-time mistress of Edward, the Prince of Wales and was a well-known society beauty, an actress and a racehorse owner.

Apart from the officials, the only other person present at the de Bathes’ wedding was Jeanne Langtry, Lillie’s daughter. Hugo, in fact, was much closer in age to his new stepdaughter than to her mother who was 18 years senior in years to him. Jeanne’s father’s name had never been revealed, though it could have been one or other of two different men that Lillie had been seeing at the time – Arthur Clarence Jones, or Prince Louis of Battenberg. Eight years after her marriage, in 1907, her husband inherited the baronetcy and so Lillie now gained the aristocratic title of Lady de Bathe.

3 June 1916 edition of The Illustrated London News in the Newspaper and Magazine records on TheGenealogist

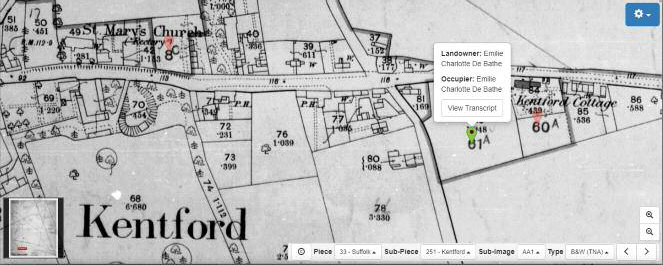

Regal Lodge identified using TheGenealogist’s Map Explorer

Tithe map records on TheGenealogist shows the altered apportionment from 7 December 1900

St Peter’s College, Radley register in the Educational Records on TheGenealogist

Ambulance driver or pilot?

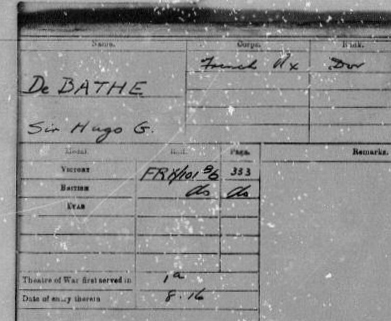

In the First World War we can find Sir Hugo listed in TheGenealogist’s Medal Cards as a driver in the French Red Cross and many online biographies speak only of this service, ignoring his later commission into the Royal Flying Corps, where he spent most of the war. The reality is that the medal card records when he first entered the theatre of war in August 1916. Consulting the London Gazette tells us that Sir Hugo was actually commissioned as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant in the RFC in September 1917 and an Air Force List found on TheGenealogist lists him appointed to the General Lists of the RFC in April 1918.

Even before embarking on his war service in the French Red Cross, Sir Hugo can be seen to have been playing his part by taking wounded soldiers out in the sidecar of his Harley-Davidson motorcycle. This we can read in the 3 June 1916 edition of The Illustrated London News to be found in the Newspaper and Magazine records on TheGenealogist.

After the war Sir Hugo and Lady de Bathe moved to the South of France, the listing in the 1929 Armorial Families in TheGenealogist’s Peerage, Gentry & Royalty records revealing his address as Villa Olga near Antibes. The couple, however, were known to live separately, her in Monaco and him in Vence between Nice and Antibes.

Lillie, Lady de Bathe, had previously kept a house in England near Newmarket to be close to her stable of racehorses. From consulting the Trade, Residential and Telephone Directories on TheGenealogist we are able to find a listing in Kelly’s Directory of Suffolk 1912 for Lady de Bathe at Regal Lodge in the village of Kentford. This had been her home for the 23 years until 1919, when she moved to Monaco, and during her time there she had received many celebrated guests, not least of whom was the Prince of Wales.

Using the Map Explorer on TheGenealogist we are able to discover the house’s exact location as Regal Lodge is marked on the OS map. A search also of the tithe records finds an altered apportionment from 7 December 1900 that identifies Emilie Charlotte de Bath as the landowner and occupier of the plot of arable land.

The Kentford property was sold in 1919 when Lillie moved to Monaco. It was here that she died in 1929 at the age of 75. Her death is recorded in the GRO Consular Deaths in the TheGenealogist’s Overseas Death records and she is buried in the family tomb in St Saviour’s Churchyard, in the parish of her birth back in Jersey. This we can see confirmed from a search of the Headstone records on TheGenealogist.

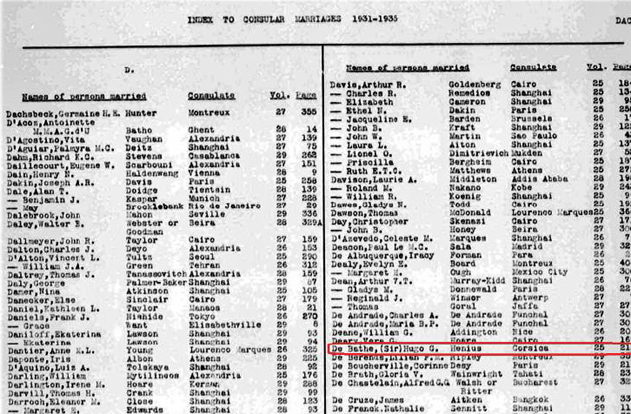

With his wife’s death in 1929 Sir Hugo can then be found recorded in the GRO Consular Marriages when he married for a second time in Corsica. It was on November 26, 1931 that Deborah Warschowsk Henius, a Dane, became the next Lady de Bathe. The broad spectrum of records that are available on TheGenealogist have allowed us to discover that it is not just the modern family that can be somewhat unconventional.

Index to Consular Marriages on TheGenealogist

First World War medal card for Sir Hugo de Bathe

Headstone Collection on TheGenealogist records Lillie’s final resting place in Jersey